A big telescope on the moon could peer deeper into the universe than James Webb

The moon may open astronomy's next frontier.

A robotic telescope on the moon could peer deeper into the universe than the famed James Webb Telescope can and perhaps even help find life on exoplanets, scientists say.

Astronomers think that powerful instruments on the moon may open the next frontier in astronomical research, allowing them to study phenomena invisible to existing ground and space-based observatories. Various ideas have been proposed, including supersensitive gravitational wave detectors that could spot more subtle ripples in space-time than Earth-based detectors can and radio telescopes that could take advantage of the moon's quiet environment to detect signals from the earliest epochs in the universe's history.

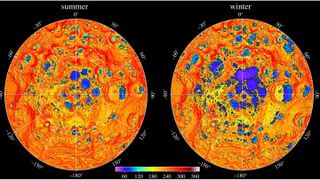

Another idea, presented by astronomer Jean-Piere Maillard at the recent Astronomy from the Moon conference held by the Royal Society in London, involves placing a 42-foot-wide (13 meters) infrared telescope inside a permanently shadowed crater near one of the moon's poles.

Related: Building telescopes on the moon could transform astronomy – and it's becoming an achievable goal

Such a telescope, Maillard told Space.com in an email, would be more sensitive than the current star of infrared astronomy, NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, and see parts of the electromagnetic spectrum that are invisible to Webb.

"The primary mirror of JWST is 6.5 meters [21 feet] in diameter. The telescope implemented on the moon could be 13 meters [42 feet] in diameter, meaning a collecting area four times larger [than Webb's]," Maillard, an astronomer at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, wrote in the email. "Therefore, with four times more light from a source, it would be more sensitive in the common 1 to 28 micrometers domain. And having this collecting area, it would be able to observe the largely unexplored domain beyond 28 micrometers."

What Maillard is referring to is the part of the electromagnetic spectrum that the James Webb Space Telescope can detect — radiation of wavelengths between 0.6 to 28 micrometers, which includes near-infrared and mid-infrared light. Infrared wavelengths are slightly longer than what human eyes can see and can be perceived as heat. By detecting infrared radiation, the James Webb Space Telescope can glimpse even those objects that are too cold to visibly glow.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But even Webb has its limit, Maillard explained. This limit is dependent on the telescope's temperature as well as the size of its mirror. An infrared telescope located in a permanently shadowed lunar crater could not only be bigger, but also colder and therefore capable of detecting even cooler phenomena.

"The maximum infrared limit comes from the temperature to which the telescope can be cooled down," Maillard said. In the case of the James Webb Space Telescope, the cool conditions are provided by a five-layer sunshield that protects the telescope, which is located 1 million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth, from sun rays and the heat emitted by our planet. But "in some craters at the lunar poles, much colder spots exist," Maillard added. "By implementing a telescope there, without the need of any screen or any mechanical refrigerator, the telescope and its instrument are put at the very low temperature of the site."

Thanks to such cold temperatures, a lunar infrared telescope could detect the far infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum — radiation with wavelengths up to 200 micrometers.

Far infrared wavelengths cannot be seen by any existing telescope. NASA's recently retired flying observatory SOFIA was a specialist in studying this type of light. But that telescope, capable of detecting wavelengths from 5 to 612 micrometers, was retired in 2022 due to the high cost of its operations following a recommendation by the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

No replacement telescope with similar capabilities is currently in the works. As a result, astronomers currently cannot study many types of cosmic phenomena that reveal themselves only in the longer infrared wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum. And there is a wealth of data in that range, just waiting to be gathered: Longer wavelengths travel much better than shorter ones through the dust and gas that fills intergalactic space, carrying much information about the distant universe as they move.

The infrared telescope on the moon proposed by Maillard and his colleagues would not only reveal a portion of those currently invisible phenomena, it would also be better than Webb in analyzing atmospheres of exoplanets orbiting stars in the Milky Way galaxy. In that way, such a telescope would help scientists zoom in on exoplanets that might harbor life.

"Many molecules and atoms are only detectable beyond 25 micrometers," Maillard wrote. "That is the case, for example, for H2O, and it would be essential in the observation of exoplanets to conclude if it could be a habitable world."

Mailard added that a lunar infrared telescope with a 42-foot-wide mirror could be possible within the "next decades" even without a permanent human presence on the moon, as it could be built and maintained by robotic technology.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.