First Exomoon Found? Neptune-Sized World Possibly Spotted Orbiting Alien Planet

Scientists may have bagged the first-ever exomoon.

NASA's Kepler and Hubble space telescopes have spotted evidence of a Neptune-size satellite orbiting the Jupiter-like planet Kepler-1625b, which lies about 8,000 light-years from Earth, a new study reports.

"We've tried our best to rule out other possibilities such as spacecraft anomalies, other planets in the system or stellar activity, but we're unable to find any other single hypothesis which can explain all of the data we have," co-author David Kipping, an astronomer at Columbia University in New York, told reporters earlier this week. [The Hubble Space Telescope: A 25th Anniversary Photo Celebration]

Still, he and lead author Alex Teachey, also a Columbia astronomer, stressed that the observations don't constitute a definitive detection.

"We hope to re-observe the star again in the future to verify or reject the exomoon hypothesis," Kipping said. "And if validated, the planet-moon system — a Jupiter with a Neptune-sized moon — would be a remarkable system with unanticipated properties, in many ways echoing the unexpected discovery of hot Jupiters in the early days of planet hunting."

Hunting for exomoons

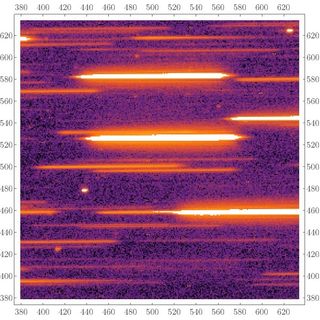

The new results come from a concerted exomoon hunt Teachey and Kipping conducted using data from Kepler, which has discovered about 70 percent of the 3,800 known exoplanets to date. Kepler finds worlds via the "transit method," noting the tiny dips in star brightness caused by orbiting planets crossing their stars' faces.

Previous research has suggested that big (and therefore detectable) exomoons are rare around large planets that orbit very close to their parent stars. Such satellites would likely be lost during the chaos-inducing inward migration undertaken by these giants after their formation, the thinking goes.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Teachey and Kipping therefore studied Kepler observations of 284 planets with relatively wide orbits — worlds that take at least 30 Earth days to complete one lap. And they noticed weird deviations in the "light curve" generated by the 19-hour-long transit of Kepler-1625b, a planet about three times heftier than Jupiter that orbits a star about as massive as our own sun. (In 2017, the researchers reluctantly announced the discovery of these oddities in the three transits Kepler observed, after word of them leaked out on Twitter.)

So the duo applied to study the planet with Hubble, and were awarded 40 hours of observation time with the iconic telescope. They succeeded in observing another transit in late October 2017 — and saw two "substantial anomalies," according to Kipping.

"The first is that the planet appears to transit one and a quarter hours too early; that’s indicative of something gravitationally tugging on the planet," he said. "The second anomaly is an additional decrease in the star’s brightness after the planetary transit has completed."

A moon orbiting Kepler-1625b is the best explanation, Teachey and Kipping said. There's no indication of another planet in the system that could be tugging on Kepler-1625b, and the secondary dimming is consistent with a moon trailing the gas giant during its transit. [7 Greatest Alien Planet Discoveries by NASA's Kepler Spacecraft (So Far)]

A very big moon

The Kepler and Hubble observations, along with modeling work, suggest that the moon is about the size of Neptune and 1.5 percent as massive as Kepler-1625b. That latter number explains why the duo refers to the big candidate object as a satellite, Teachey said.

"When we derived the mass ratio, that's really sort of what I would say, in court, defines the difference between a planet and a moon or a binary planet," he said. "I would call that a moon, but to some extent I think this is something of semantics — what people want to define as a planet and moon or a binary system."

Indeed, the mass ratio is similar for our own Earth-moon system — 1.2 percent.

The candidate exomoon orbits 1.9 million miles (3 million kilometers) from its host planet — about eight times farther away than Earth's moon circles. But because it's so big, the object would be about twice as big in Kepler-1625b's skies as Earth's moon is in ours, Teachey and Kipping said.

Astronomers know of three major moon-formation mechanisms: There's gravitational capture (which appears to be the case with Neptune's biggest moon, Triton); powerful impacts (as happened with Earth's moon, which formed from material blasted into space by a long-ago collision); and the merging of material from a disk of material surrounding a newborn planet.

The capture and impact scenarios are implausible for such a large moon, Kipping said. So the candidate body probably coalesced from a circumplanetary disk, as the big Galilean moons of Jupiter did.

Kepler-1625b appears to orbit in its star's habitable zone, the just-right range of distances where liquid water might be stable on a world's surface. But the moon is so big that it's almost certainly gaseous, with no discernible surface, Teachey said.

So you should probably tamp down any Pandora- or Endor-related thoughts that might be running through your head, as the moon doesn't seem to be a great bet for alien life (at least not "advanced" life).

And there's another wrinkle to the habitability story. Though Kepler-1625b's host star is sunlike, it's thought to be about 10 billion years old — more than twice as old as Earth's star. So it's much farther along in its life cycle and is therefore probably quite a bit warmer than the sun.

This raises the possibility that the candidate exomoon isn't actually as massive as it may appear. Rather, it may have been puffed out relatively recently by the increased influx of stellar radiation. Indeed, some of the duo's models allow for a mass as low as that of Earth, Teachey said.

"But this is really a bit more speculative here," he stressed. "We don't have any evidence to think that directly, to prove that this is what has been happening in the past of this planet. But there's certainly interesting games that you can play when you acknowledge that this star is in this transitional phase."

Nailing it down

Again, the moon under discussion here remains a candidate, not a confirmed body. Confirmation could come quickly with further observations, however.

Indeed, it may take just a single additional transit observation that shows a "separate clean moonlike event," Kipping said.

"If we see that, then I think we're done," he said. "If we don't see it, then there is a fraction of our models which actually allow that still to happen. And it would have to go from there. It's difficult to predict exactly what the data will give us, until we actually see it in that scenario."

He and Teachey hope to make that additional observation with Hubble. Ground-based telescopes are not an option, because Earth's rotation takes Kepler-1625b and its star out of view long before the transit is complete, Teachey explained.

The new study was published online today (Oct. 3) in the journal Science Advances.

Editor's note: This story has been corrected from an earlier version that included one reference to the primary planet of the potential exomoon as WASP-1625b. The planet's name is Kepler-1625b.

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There," will be published on Nov. 13, 2018. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.