Lost in Space: Half of All Stars Are Rogues Between Galaxies

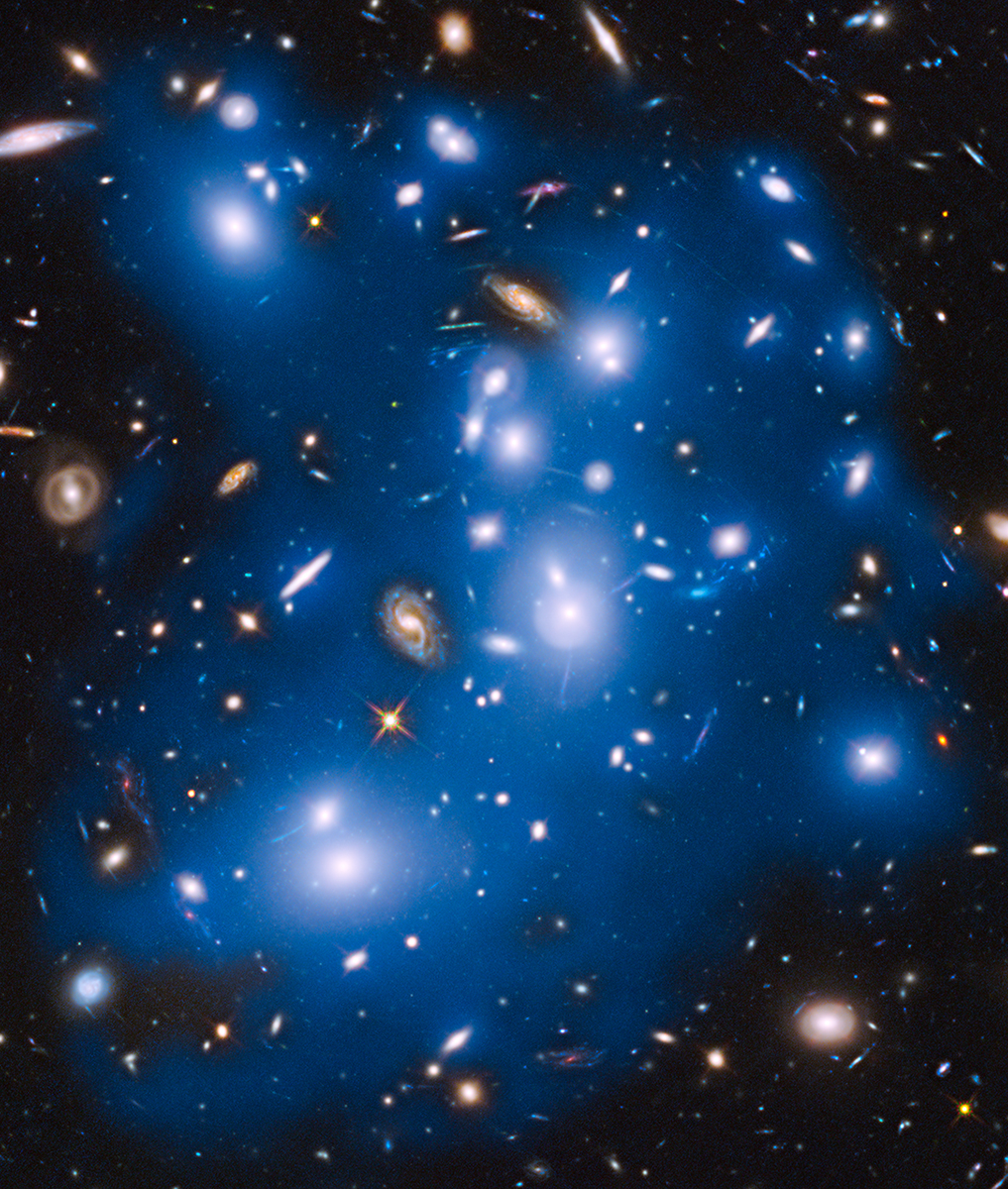

As many as half of all stars in the universe lie in the vast gulfs of space between galaxies, an unexpected discovery made in a new study using NASA rockets. These stars could help solve mysteries regarding missing light and particles that theory had suggested should exist, scientists say.

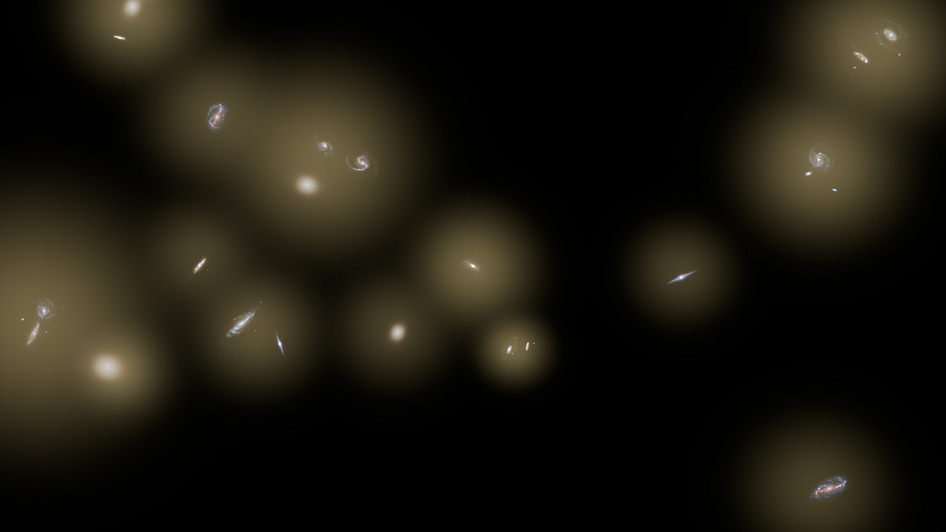

In the study, astronomers investigated the extragalactic background light, the sum of all light emitted by stars in the universe throughout history. Prior research had detected fluctuations in this light that did not appear to come from any known galaxies. Scientists had suggested these fluctuations might come from primordial galaxies, the very earliest galaxies, whose light has yet to be detected.

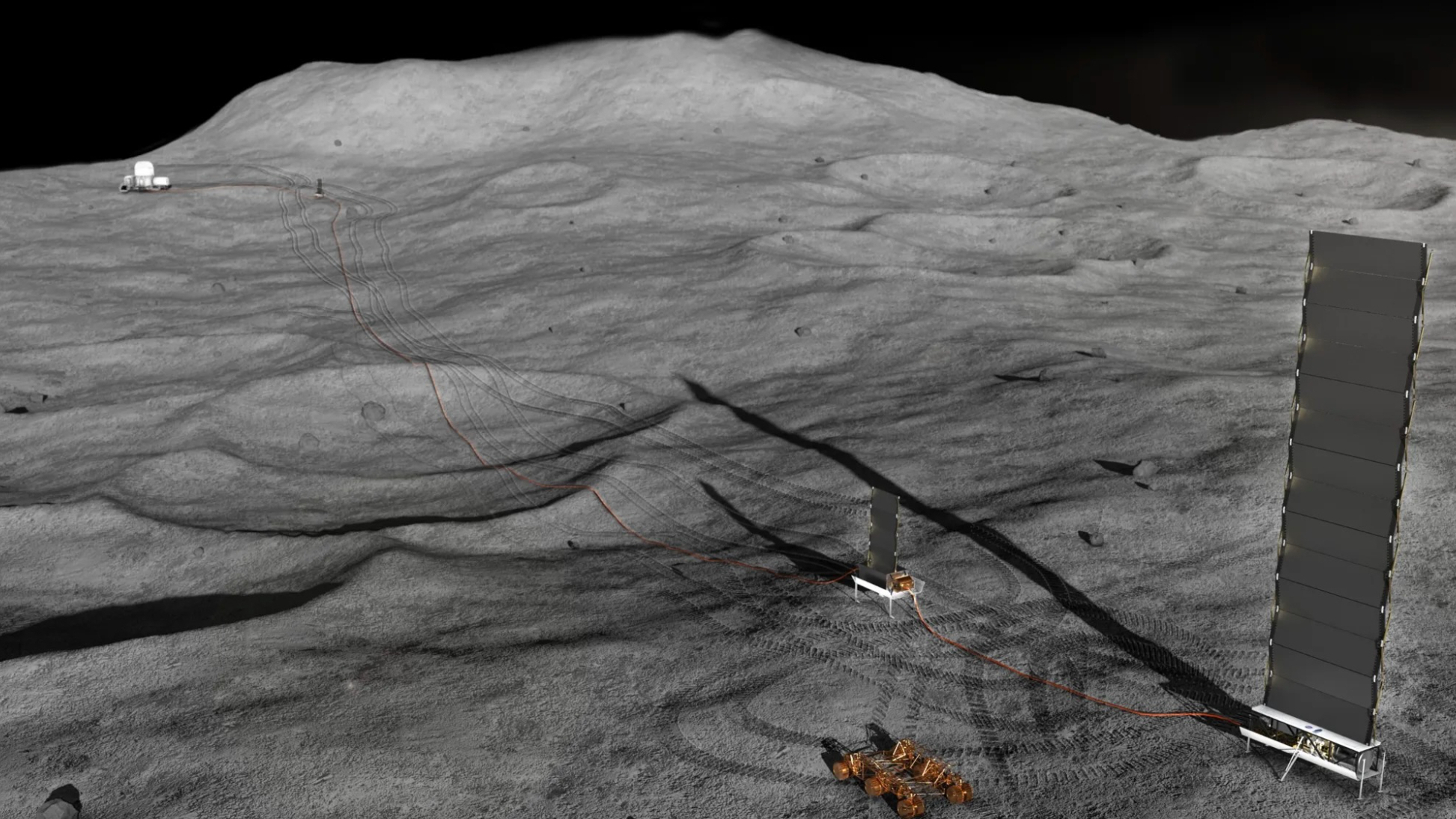

To investigate those fluctuations, researchers developed the Cosmic Infrared Background Experiment (CIBER), made up of a set of telescopes specifically designed to analyze the properties of the extragalactic background light. They flew CIBER on two NASA rockets launched into space in 2010 and 2012. [Greatest Star Mysteries of All Time]

"We use CIBER to study an area of the sky 20 times the area of the full moon,"said study co-author James Bock, an experimental cosmologist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. "We take out all the light produced by individual galaxies and look at what's left."

Small rockets, big science

CIBER made use of small rockets known as sounding rockets, which are research missions that go into space but not orbit. "We needed our instruments to be above 60 miles (100 kilometers) in altitude, but we didn't need to be up there long, and a sounding rocket was a great way to quickly and affordably conduct these experiments," Bock said.

The researchers concentrated on fluctuations in the near-infrared region of the extragalactic background light, since the visible and ultraviolet light from stars in primordial galaxies should have reddened over time as the universe expanded. (This phenomenon is known as redshifting.) They validated their results with NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope.

Results suggested that primordial galaxies were not, in fact, the source of the background light fluctuations, as the scientists discovered the fluctuations were too bright and blue to come from primordial galaxies. Since these first galaxies are very old, any of their light seen now would have been emitted billions of years in the past, and if this light traveled such a long amount of time, it should appear relatively dim and red because of gas it had to pass through.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Instead, this finding of bright, blue light unexpectedly reveals these fluctuations may come from something called "intrahalo light," which is created by stars flung into intergalactic space during titanic collisions and mergers of galaxies. The researchers found that there was as much light from these intergalactic stars as there was from stars located in galaxies.

"This light is equal to all the light from stars in galaxies," Bock told Space.com. "This is telling us that stars are torn from their galaxies more often than previously thought."

A star mystery solved?

These newfound stars could help solve the so-called "photon underproduction crisis," which suggests that an extraordinary amount of ultraviolet light appears to be missing from the universe.

The intergalactic stars could also help address what is known as the "missing baryon problem." Baryons are a class of subatomic particles that includes the protons and neutrons that make up the hearts of atoms inside normal matter. Theories of the formation and evolution of the universe predict there should be far more baryons than scientists currently see. The baryons that astronomers have accounted for in the local cosmic neighborhood are only half of those predicted to exist in that region.

The study's scientists are now analyzing data from other instruments on the two sounding rockets they launched, as well as results from two other sounding rockets they sent into space. "We hope to learn more about how these stray stars are produced," Bock said.

The researchers detailed their findings in the Nov. 7 issue of the journal Science.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us