Monstrous Whirling Gas Cloud Reveals Clues About Galaxy Formation

For the first time, astronomers have spotted a protogalactic disk — a giant whirling cloud of gas that gives birth to a galaxy — and the discovery could reveal clues about how galaxies form.

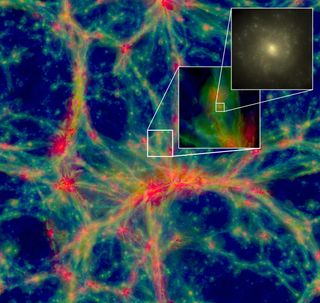

Galaxies are strung together in filaments separated by immense voids. These filaments are connected in a gargantuan tangle known as the cosmic web.

Much remains a mystery about how galaxies form. Researchers suggest that a key player is a kind of current known as a cold accretion flow. These rivers of gas can get as hot as 18,000 degrees Fahrenheit (10,000 degrees Celsius) — they are only "cold" relative to the kinds of extraordinarily hot winds astronomers regularly see in the universe, such as those around black holes. [Images: Black Holes of the Universe]

One model suggests that, at the points where these filaments intersect, cold accretion flows streaming along the cosmic web's filaments create disklike or ringlike structures, and that these "protogalactic disks" eventually coalesce into galaxies.

To learn more about how galaxies are born, scientists analyzed the first filament that astronomers ever imaged, a giant structure 1.5 million light-years long and 10 billion light-years away from Earth that was discovered in 2010.

This filament is about one-third as bright as the Milky Way, making it 3 billion times more luminous than the sun and more than 10 times brighter than what is expected for a filament. The filament is probably unusually radiant because it is illuminated by a quasar, the brightest type of object in the universe, researchers have said.

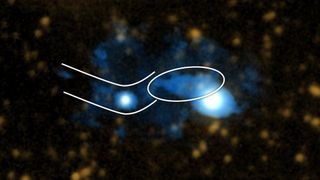

Using the Cosmic Web Imager at Palomar Observatory in California, the scientists discovered that the brightest spot in the filament is a spinning protogalactic disk of hydrogen.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It is rare and surprising to discover a completely new kind of object," said study lead author Christopher Martin, an astrophysicist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

The researchers found that this protogalactic disk is more than 407,000 light-years wide, weighs as much as about 100 billion suns, and is surrounded by a "halo" of invisible dark matter weighing as much as 10 trillion suns. For comparison, the Milky Way may be 160,000 light-years in diameter, and it weighs perhaps 1 trillion suns.

These findings reveal how cold accretion flows might help build protogalaxies — clouds of gas that give birth to galaxies, Martin said.

"It is extremely rare in astrophysics to be able to uncover the physical processes behind an observed phenomenon," he told Space.com. "In this case, we will be able to study the processes that form the basic constituent of the universe, galaxies."

In the future, Martin and his colleagues plan to find more protogalactic disks and study them with a larger telescope and better instruments.

"We are about to commission the perfect instrument for this — the Keck Cosmic Web Imager, which will be mounted at the Nasmyth focus of the W. M. Keck Observatory Keck II telescope [in Hawaii]," Martin said. "We plan to start observing at the beginning of 2016 with the Keck Cosmic Web Imager."

The scientists detailed their findings online today (Aug. 5) in the journal Nature.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us