Spring on Saturn's Moon Titan Reveals Amazing Views of Otherworldly Lakes (Photos)

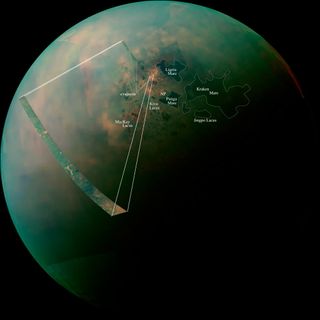

NASA's Cassini space probe is getting an exceptional look at the vast liquid lakes of Titan's north pole, where dense winter clouds are finally retreating thanks to a change in seasons on Saturn's largest moon.

A clearer view of Titan's wet northern region could provide clues about the moon's hydrologic cycle and the evolution of its seas. New images released by NASA this week even revealed the Titan equivalent of salt flats surrounding its northern lakes, some of which are as big as the Caspian Sea and Lake Superior combined.

Titan more closely resembles Earth than any other planet or moon in our solar system, with a dense atmosphere and stable liquids on its surface. But Titan's clouds, lakes and rain are made up of hydrocarbons, such as ethane and methane, rather than water. [Amazing Photos: Titan, Saturn's Largest Moon]

The vast majority of Titan's liquid bodies are found in its north pole, but this region had been shrouded in a thick cap of haze ever since Cassini arrived in the Saturn system in 2004. Recently, that northern ice cloud has been dissipating and a similar one is forming over the moon's drier south pole, signaling a change in seasons for Titan.

"Titan's northern lakes region is one of the most Earth-like and intriguing in the solar system," Cassini project scientist Linda Spilker, based at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., said in a statement.

"We know lakes here change with the seasons, and Cassini's long mission at Saturn gives us the opportunity to watch the seasons change at Titan, too," Spilker added. "Now that the sun is shining in the north and we have these wonderful views, we can begin to compare the different data sets and tease out what Titan's lakes are doing near the north pole."

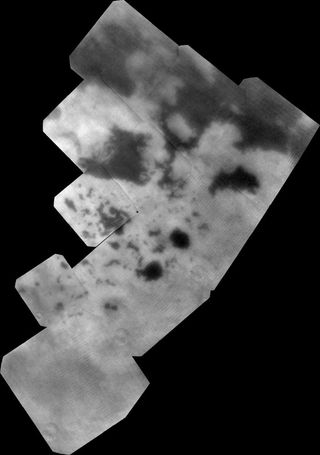

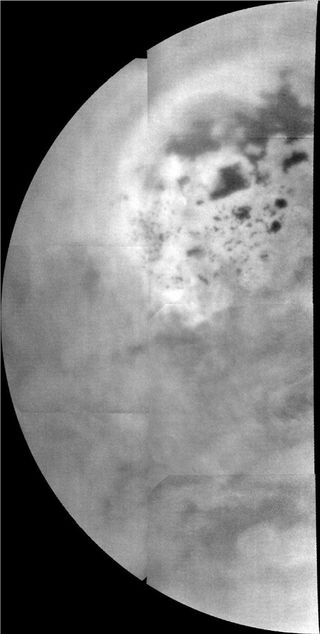

The mosaics images released by NASA are based on infrared data from Cassini's flybys of Titan on July 10, July 26, and Sept. 12, 2013.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The false color image highlights the differences in the composition of material around the lakes, with the orange blotches thought to be organic chemicals left behind long after a liquid body evaporated — similar to the way salt pans form on Earth after pools of water evaporate, leaving behind a flat stretch of salt and other minerals.

"The view from Cassini's visual and infrared mapping spectrometer gives us a holistic view of an area that we'd only seen in bits and pieces before and at a lower resolution," Jason Barnes, a participating Cassini scientist at the University of Idaho, Moscow, said in a statement. "It turns out that Titan's north pole is even more interesting than we thought, with a complex interplay of liquids in lakes and seas and deposits left from the evaporation of past lakes and seas."

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @SPACEdotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Megan has been writing for Live Science and Space.com since 2012. Her interests range from archaeology to space exploration, and she has a bachelor's degree in English and art history from New York University. Megan spent two years as a reporter on the national desk at NewsCore. She has watched dinosaur auctions, witnessed rocket launches, licked ancient pottery sherds in Cyprus and flown in zero gravity on a Zero Gravity Corp. to follow students sparking weightless fires for science. Follow her on Twitter for her latest project.