Cosmic 'Murder Mystery' Solved: Galaxies Are 'Strangled to Death'

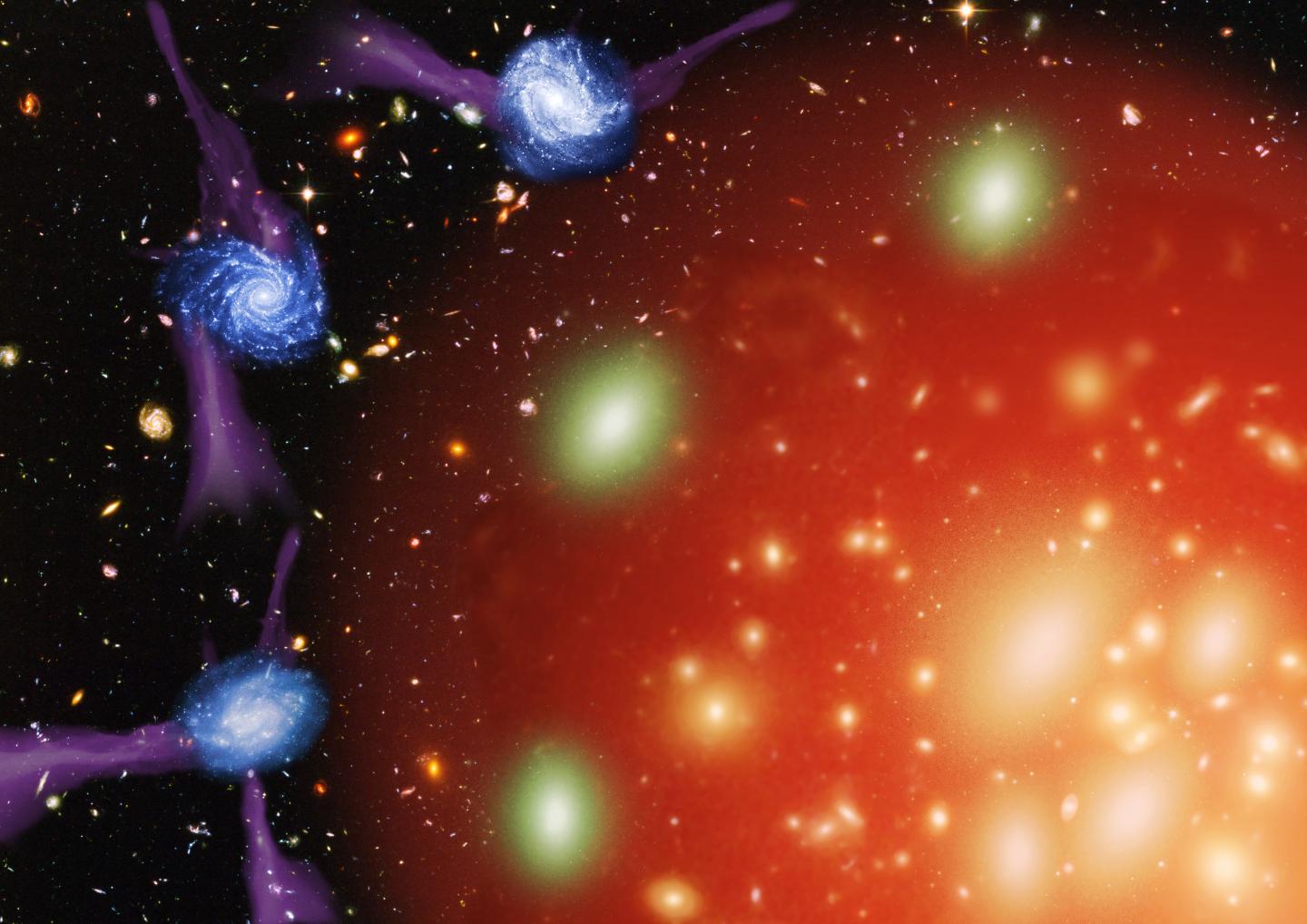

Astronomers may have solved the decades-long cosmic murder mystery of what kills most galaxies in the universe: They are strangled to death, so they can no longer create new stars.

For two decades, astronomers have known that there are two main classes of galaxies. About half are live, gas-rich galaxies where stars form, and the other half are dead, gas-deprived galaxies where stars do not form, said study lead author Yingjie Peng, an astronomer at the University of Cambridge in England.

Until now, scientists were unsure of what stifled star formation in galaxies. "What kills galaxies is one of the most challenging questions in the past 20 years," Peng told Space.com. [When Galaxies Collide: Amazing Space Photos]

Scientists have proposed two ideas for what may extinguish star formation in galaxies. One explanation is known as strangulation, in which the supply of the cold gas needed to fuel star formation in a galaxy is slowly choked off. The other involves the sudden removal of gas from a galaxy, perhaps stripped off by the gravitational pull of another galaxy.

By analyzing more than 26,000 nearby galaxies, the researchers have found clues revealing the cause of the deaths of most galaxies: strangulation.

"This is the first conclusive evidence that galaxies are being strangled to death," Peng said.

Stars are composed mostly of hydrogen and helium. The researchers focused on concentrations of "metals" — elements heavier than hydrogen and helium — in galaxies. Such "metals" are formed when stars fuse hydrogen and helium into heavier elements.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The scientists found that dead galaxies had much higher amounts of metals than live galaxies did. This finding is consistent with how strangulation would lead galaxies to evolve over time, Peng said.

After a galaxy's gas supply is choked off, it still has some gas left inside that can be used to form stars. In turn, these stars can form elements heavier than hydrogen and helium. In contrast, in galaxies where gas is suddenly removed, star formation stops abruptly too, leading to less metals.

The computer models suggested that strangulation takes about 4 billion years to extinguish star formation. This is consistent with the age difference seen between star-forming and "dead" galaxies, the investigators said.

The researchers said the strangulation theory accounts for galaxies up to 100 billion times heavier than the sun, which make up more than 95 percent of all galaxies. For larger galaxies, the evidence was not conclusive for either the strangulation or sudden-removal theories, Peng said.

Although the researchers have found that most galaxies die via strangulation, they still need to better understand the mechanism that causes the strangulation, Peng said. One possibility is that nearby galaxies may help deplete a star-forming galaxy's gas supply, Peng added.

The team's investigation analyzed relatively nearby galaxies, and the next step will be to look at more distant galaxies, which provide a picture of what the universe looked like when it was young. This further research will enable researchers to establish a more complete picture of how galaxies form and evolve, Peng said.

"We have many forthcoming powerful instruments, such as the Multi-Object Optical and Near-infrared Spectrograph (MOONS), and telescopes such as the space-based James Webb Space Telescope, which will make our research plan feasible in the next few years," Peng said.

Peng and his colleagues detailed their findings in the May 14 issue of the journal Nature.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us