The patch of Mars where NASA's Curiosity rover touched down Sunday night (Aug. 5) has a name: Yellowknife.

The moniker is a tribute to the capital of Canada's Northwest Territories, a city that has long served as the jumping-off point for geologists interested in studying North America's oldest rocks, scientists said.

"If you ask, 'What is the port of call you leave from to go on the great missions of geological mapping to the oldest rocks in North America?' — it's Yellowknife," Curiosity chief scientist John Grotzinger, of Caltech in Pasadena, told reporters Friday (Aug. 10).

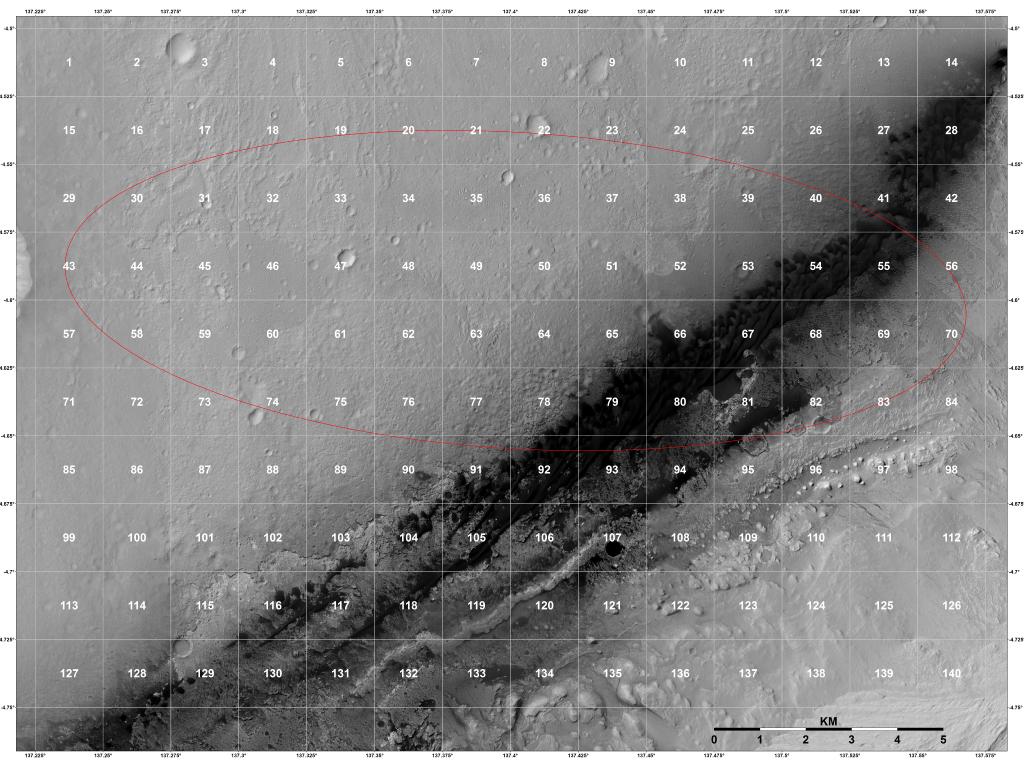

In the home stretch of Curiosity's eight-month space cruise, Grotzinger and his team divided the rover's predicted landing zone inside Mars' Gale Crater into a set of 151 "quadrangles," each of which measures about 1 mile (1.6 kilometers) on a side.

The idea was to break the work of characterizing the landing zone into manageable chunks. The Curiosity rover landed on Quadrangle 51, which the team has dubbed Yellowknife.

Curiosity's main mission is to determine if the Gale Crater area could ever have supported microbial life. Mars appears hostile to Earth-like life today, at least on the surface. But things might have been different in the past, which is why the rover team is drawing connections with the 2.7-billion-year-old rocks of northwest Canada.

"We went to Mars to really get at the ancient geology, because that's where we think there might be evidence for past environments similar to on Earth," said Curiosity deputy project scientist Joy Crisp, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "So it's connected in that way — simply, ancient rocks that might preserve evidence of past environments favorable for life."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Curiosity will likely be in Yellowknife for a while (the rover won't even take its first drive for two weeks or so), but eventually the six-wheeled robot will leave the quadrangle to explore more of Gale and to investigate Mount Sharp, the mysterious 3-mile-high (5 km) mountain that rises from the crater's center.

The mission team is not in a big rush. Curiosity's prime mission is slated to last about two Earth years, and the rover's nuclear power source may keep it roaming for considerably longer than that if no key parts break down, researchers have said.

Visit SPACE.com for complete coverage of NASA's Mars rover Curiosity. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.