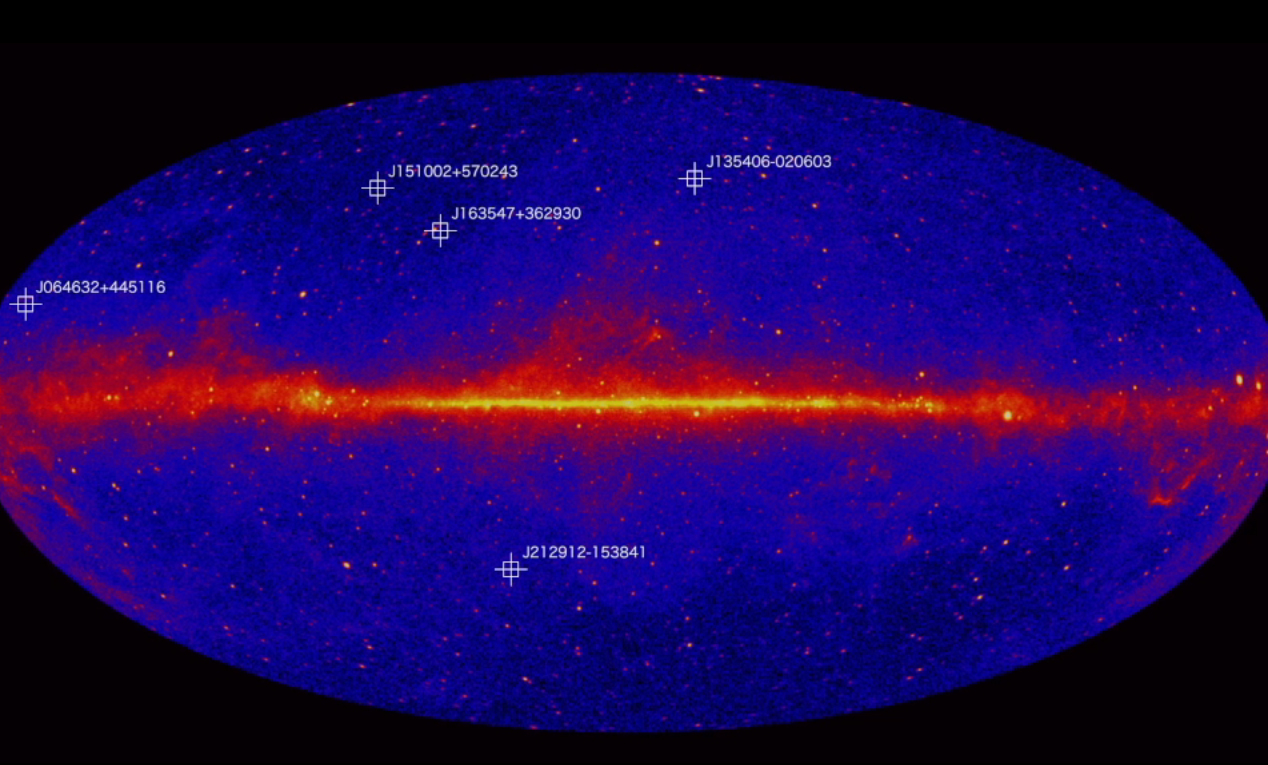

These Powerful Blazars Are the Most Distant Ever Seen

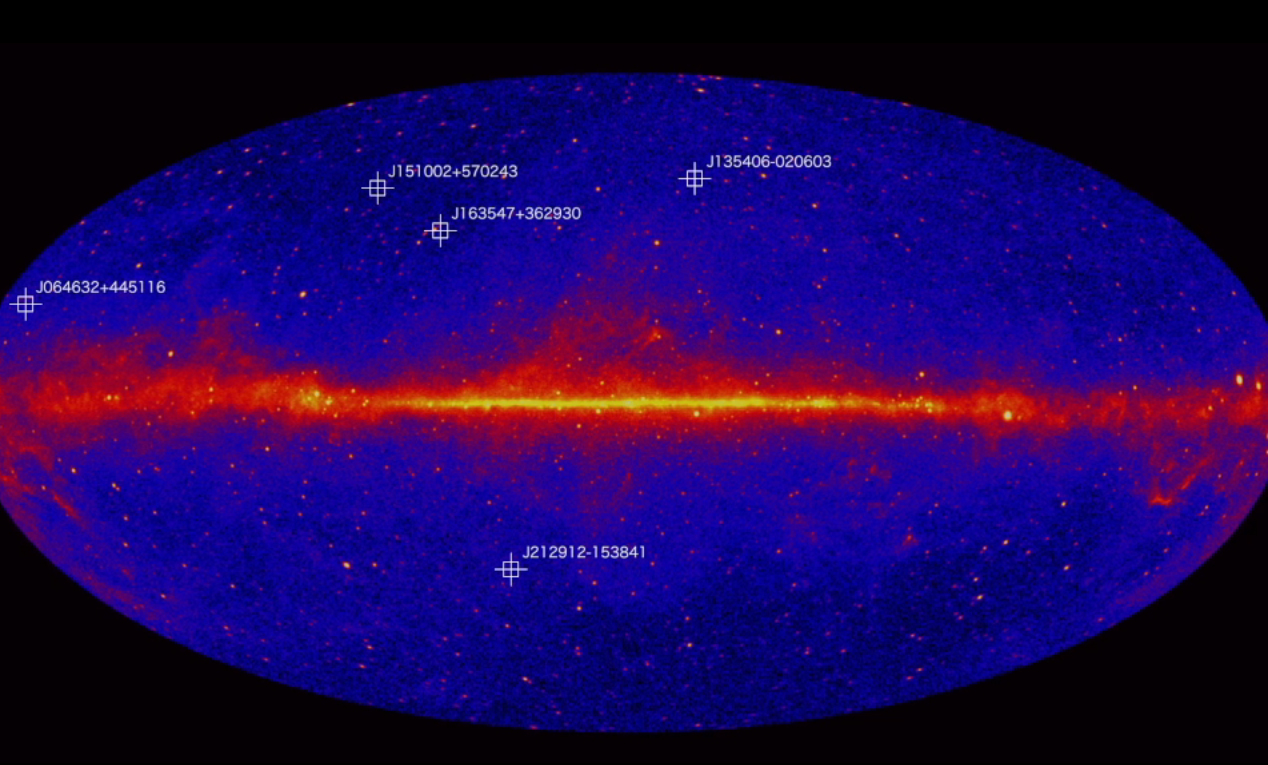

Monster black holes shooting jets of gamma-ray radiation right at us have been spotted farther away than ever before, dating back to when the universe was nearly one-tenth its current age.

The five distant objects, called gamma-ray blazars, deepen the mystery of how black holes so large could have formed so early in the universe's history.

Roopesh Ojha, an astronomer at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, presented the new results during a press conference today (Jan. 30) at the American Physical Society meeting in Washington, D.C. The results will also be published in The Astrophysical Journal Supplement. [Found: Gamma-Ray Blazars Powered by 'Supersized' Black Holes (Video)]

"The light we observed from these five objects left when the universe was just somewhere between 1.9 to 1.4 billion years old," Ojha said. Based on the data, "you arrive at the conclusion that they're all home to really, really massive black holes. Two of them are so big that their black holes may be well over 1 billion solar masses."

The supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy, in contrast, has a mass of between 4 and 5 million times the sun's.

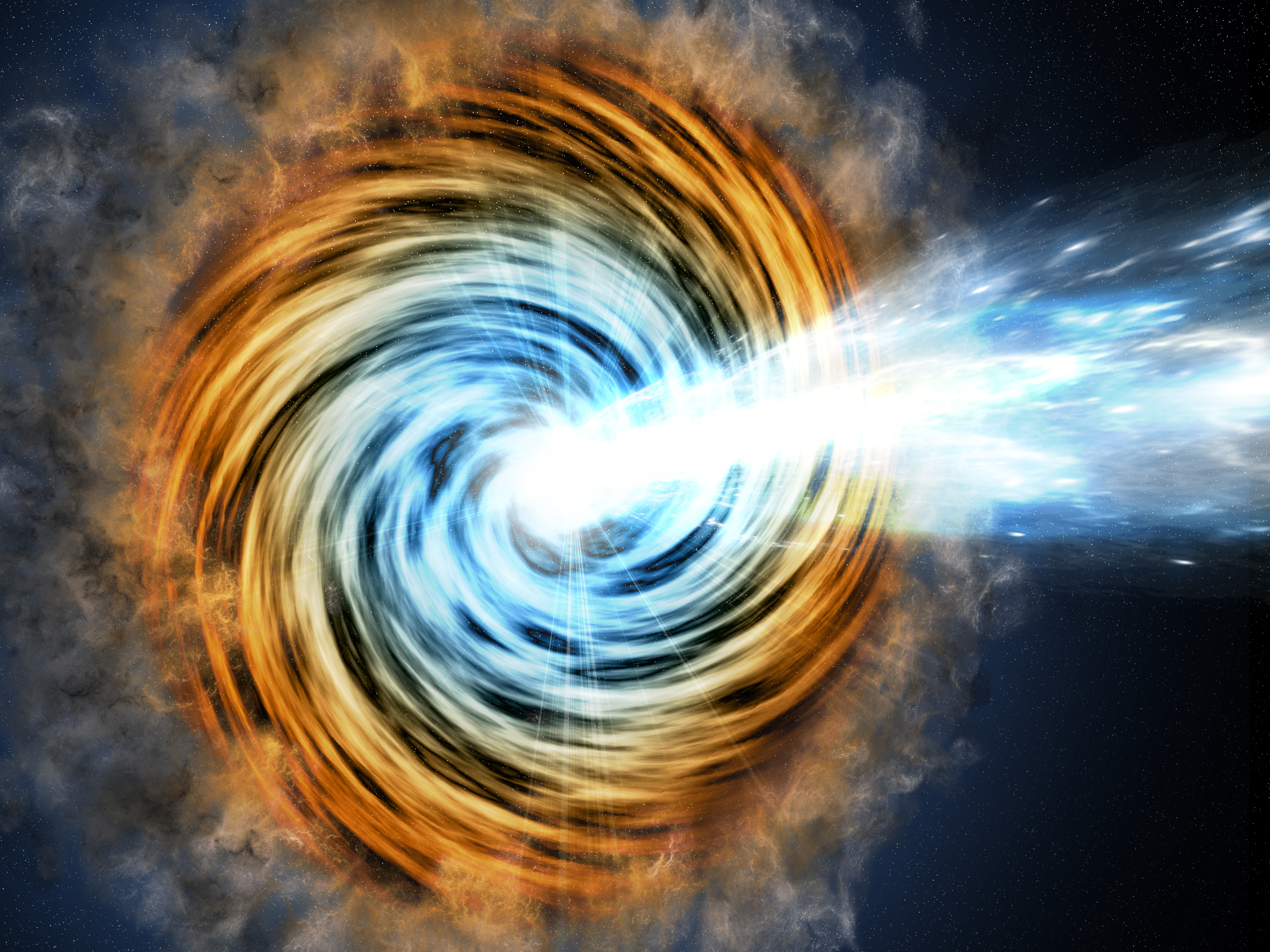

A blazar is a class of active galactic nuclei — a supermassive black hole at the center of a galaxy with a large disk of material whirling around it (outside the black hole's point of no return), generating radiation that blasts out in hyperfast jets. Blazars are the most active, from Earth's perspective, because the jets of material are speeding right toward us at near the speed of light. The new study looked at a particular type of blazar that's even more active than usual, Ojha said — and those blazars tend to spark from incredibly massive black holes, even compared to other galactic cores.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

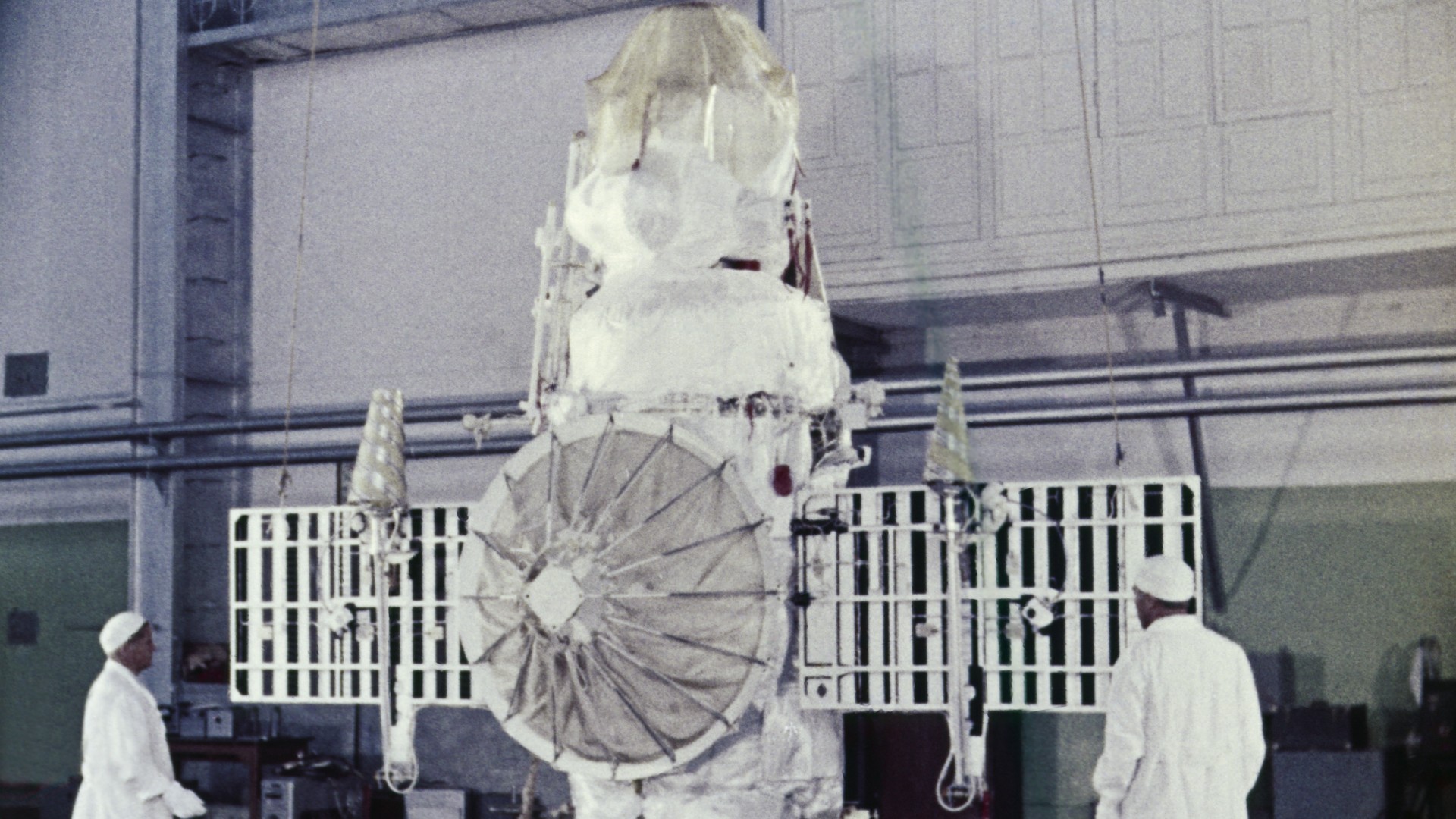

Before these five blazars were detected, the most distant blazar that had been seen emitted its light when the universe was close to 2.1 billion years old. The team, led by two researchers at Clemson University in South Carolina, was able to find blazars even more distant because of a significant processing software update to the orbiting Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope's Large Area Telescope, which increased its sensitivity by about 40 percent, particularly at lower frequencies, Ojha said.

The five newfound blazars are only a few of the many similarly powerful objects that must have existed that early in the universe's history — after all, we only detected the ones whose fierce jets are pointed directly at us.

"For a typical value of one of these objects, for the one object you see, there's something closer to 600 that you don't see," Ojha said. And that further emphasizes a major question about the early universe: How did black holes so large form so quickly?

"We've probably just made this problem a little bit more difficult by finding objects that are so massive," Ojha said.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.