A Fake Asteroid Headed to Earth Can Really Make You Think

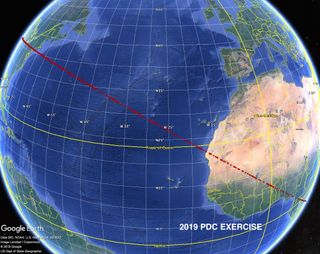

It's one thing to talk about the possibility of an asteroid striking Earth and what humanity could do about it. It's a very different thing to see an angry red slash crossing a huge swath of the planet from Hawaii, over the continental United States and through Africa, marking where a large, albeit hypothetical, asteroid could fall.

That's precisely what confronted a roomful of asteroid scientists, planetary-defense experts, decision makers and emergency management personnel at the International Academy of Astronautics' Planetary Defense Conference, held in College Park, Maryland, last week.

"It was really an interesting and fun opportunity to participate in the simulation exercise," Lori Glaze, director of NASA's Planetary Sciences Division, told Space.com. "I said it was fun because it was great to see so many people really thinking through all the various angles of how we would, as a society, an international human society, how we would try to deal with a potential threat to the planet."

Related: This Scientist Is Creating Fictional Asteroids to Save Humanity from Armageddon

That exercise spanned nearly the entire timeline of such a crisis, with scientists spotting the hypothetical asteroid in March 2019, visiting it with a flyby reconnaissance spacecraft, attempting to deflect it, realizing that the attempt had failed and determining that a small fragment would obliterate most of Manhattan in just 10 days. (None of these events is real.)

The fictional asteroid was carefully constructed by Paul Chodas, a real scientist at NASA's Center for Near Earth Object Studies, who has been designing asteroid scenarios since the 1990s. But there's a lot of value in looking at the many different types of havoc an asteroid could wreak, he said.

"As we get to more fidelity on these [simulations], it raises issues I never thought of," Chodas told Space.com. "We're bringing in new people working on the problem. … Frankly, we're getting lots of great ideas from new faces."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Such exercises also give the planetary defense community — the subset of asteroid scientists and spacecraft designers who are thinking about how to find and avert threatening asteroids — a chance to hear from experts in other fields, like emergency response. And while an asteroid may be an exotic type of emergency, it's not exotic enough to faze those experts.

"We really approach disaster from an all-hazards perspective," Damon Penn, an assistant administrator at the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency, told Space.com. "So, not so much interest in what caused the disaster, but [instead in] what are the outcomes and what is the population that needs to be served."

Unlike many more-conventional emergencies, with an asteroid, there's a chance that scientists could offer years of warning. During the conference's scenario, the hypothetical asteroid was spotted eight years before impact. But there was plenty of information that attendees were forced to go without during the main decision-making period, held on April 30.

That's when Glaze acted as the head of a task force assembled to determine the U.S. response after hearing from representatives of groups, like astronomers observing the object, mission designers and the public. (In the scenario, this task force meeting took place at the end of July.)

Related: Huge Asteroid Apophis Flies by Earth on Friday the 13th in 2029

That response, backed by a hypothetical $2 billion, included reaching out to the United Nations, organizing a campaign to get better data on the object from the ground, putting together a reconnaissance spacecraft and designing missions that could deflect the space rock. As Glaze presented that plan to the conference attendees, she was clearly living in the scenario, laughingly referencing that she was speaking off 20 minutes of briefings and 30 seconds of thought. But she said the exercise gave her real perspective into the planetary defense aspects of her department and the larger context it fits into.

"Some aspects of it are similar to my job in that I have to rely on a lot of subject matter experts that are out there that bring me their best recommendations and then I try to make the best decisions possible," Glaze said. "Being at the conference and watching those scenarios playing out in real time really helps my perspective and my genuine understanding of that full breadth of what planetary defense means within my organization."

She said dealing with the uncertainty was the biggest struggle in the exercise. "We know we have to move quickly if we're going to respond in time and yet knowing that by moving out quickly one would be committing lots of funding, lots of money, lots of effort and activities before we really know it's needed," she said.

That, too, is a situation that emergency management experts have to be comfortable navigating. "Sometimes, you have a high level of confidence. Sometimes you don't," Penn said. "Same thing when we're dealing with NOAA [the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration] and we're dealing with hurricanes. They're very, very good at predicting and telling us what the impacts will be, but they're also very good at telling us when it's too early to pinpoint things exactly or the situation is such that the models aren't coming together."

During the scenario, attendees experienced that sense of early uncertainty first hand, after their initial decision to try to deflect the asteroid was only partially successful — and ended up relocating the impact site from Denver to New York City.

"If you act too quickly — and this is the real art part of what I do — if you act too quickly you potentially put things into the impacted area or put people, worse, into the impacted area," Penn said. "If you act too late, then you don't have enough time to get people and things out of the impacted area. So the timing is the biggest part of that."

The simulation serves as a safe space for planetary defense experts to build connections with other types of experts and to think through some of these challenges without the real-life pressure of an actual impending impact. And that's important, said Glaze, Chodas and Penn.

"This is not too big to have discussions on. It is not too out-of-this-world to be thinking about," Penn said. "It's all part of us being prepared as a nation."

- Humanity Will Slam a Spacecraft into an Asteroid in a Few Years to Help Save Us All

- Photos: Asteroids in Deep Space

- Wow! Asteroid Ryugu's Rubbly Surface Pops in Best-Ever Photo

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.