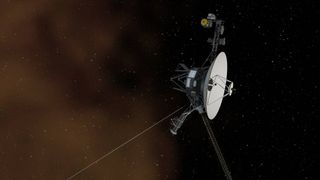

At Solar System's Edge, NASA's Voyager 2 Probe Copes with Reduced Power

It's a tiny bit colder in the outer reaches of the solar system, beyond the bubble of the sun's influence, where NASA's Voyager probes are in their fifth decade of speeding away from Earth.

NASA engineers have turned off a heater on Voyager 2 because of the continually shrinking power supply facing each of the spacecraft on their odysseys. The heater in question is paired with an instrument called the cosmic-ray subsystem instrument, which is still sending data back to Earth even at its new ambient temperature of minus 74 Fahrenheit (minus 59 Celsius). Engineers have also fired up a long-dormant thruster system on the aging spacecraft.

"The long lifetimes of the spacecraft mean we're dealing with scenarios we never thought we'd encounter," Suzanne Dodd, project manager for the Voyager mission at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, said in a statement. "We will continue to explore every option we have in order to keep the Voyagers doing the best science possible."

Related: NASA's Voyager 2 Went Interstellar the Same Day a Solar Probe Touched the Sun

The twin Voyager spacecraft, which launched in 1977, spent decades swinging through the outer solar system before making their way beyond the bubble created by the solar wind of charged particles that stream off the sun. Voyager 1 crossed this boundary in 2012; Voyager 2 followed suit in November.

Although it's been decades since the duo got a good look at a planet or moon, the type of science the probes were designed to do, they remain at work helping scientists understand the solar system. As the first and only spacecraft to cross out of the sun's bubble, called the heliosphere, they are providing critical data about the very edge of our neighborhood. (That said, the probes still have plenty of ground to cover before they leave our solar system, which stretches far beyond the distant Oort Cloud of icy bodies — all told, a journey of tens of millennia.)

When Voyager 2 bade farewell to the heliosphere last fall, it was in part the now-frigid cosmic-ray detector that gave scientists the news. That instrument began picking up much higher levels of these high-energy shattered atoms; the heliosphere blocks some, but not all, of this hail from continuing into our solar system.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Voyager 2's cosmic-ray instrument is in much chillier climes than engineers ever tested its performance in before the spacecraft launched. Voyager 1's ultraviolet spectrometer endured a similar freeze in 2012 when mission engineers turned off its heater and also continued to gather data. (Engineers on the mission turned off that instrument in April 2016 to save power.)

"It's incredible that Voyagers' instruments have proved so hardy," Dodd said. "We're proud they've withstood the test of time."

Power is a scarce commodity on the pair of spacecraft because they run on nuclear-power sources that become less and less efficient over time. By now, each of the three generators on each probe is making only about 60% of the power they did when the Voyagers launched. Engineers on the mission have been grappling with the challenge for years already and knew it would only become more pressing as the spacecraft continue their journey.

It's not just power generation where Voyager 2 is feeling its age. The spacecraft's thrusters, which keep the probe's antenna pointing toward Earth, are becoming less effective, a pattern the mission's engineers noticed in Voyager 1 in 2017. As they did with its twin, Voyager 2's managers have decided to switch to a different set of thrusters, which the spacecraft hasn't used since it flew past Neptune in 1989, although a NASA statement doesn't specify whether the flip has already occurred or is still on the to-do list.

Despite the aging pains the geriatric duo are facing, nine instruments between the two spacecraft are still working out of the 20 that took flight. And NASA personnel on the mission are confident these most-distant explorers will continue to gather valuable observations about our solar system and its surroundings.

"Both Voyager probes are exploring regions never before visited, so every day is a day of discovery," Ed Stone, project scientist for the Voyager mission, said in the same statement. "Voyager is going to keep surprising us with new insights about deep space."

- Voyager at 40: 40 Photos from NASA's Epic 'Grand Tour' Mission

- What Spacecraft Will Enter Interstellar Space Next?

- Photos from NASA's Voyager 1 and 2 Probes

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.