Follow the coils of Hydra this spring to see some of the most strikingly colorful stars in the sky.

Out of the 88 constellations, more than half represent animals or hybrids of animals. Some of these are mythological creatures that never existed, such as the unicorn, the sea goat and the two centaurs (Centaurus and Sagittarius). A few of them are in the reptile family. One of these cold-blooded creatures, which has appeared in this column on several other occasions, slithers across the southern sky on these midspring evenings. It's the largest constellation in the sky: Hydra, the water snake.

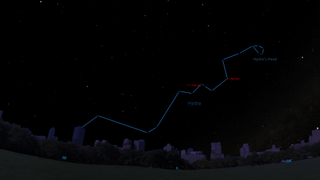

As darkness falls on spring evenings, we can trace out the entire figure of this long star pattern, starting with its head, located halfway up in the southwest sky, surrounded by stars generally associated with late winter and early spring (in the constellations Gemini, Cancer and Leo). If we follow this winding group back toward the east all the way to its end, we'll eventually come to the tip of its tail hovering low in the southeast, not far from the star patterns we would associate with early summer (Libra, Scorpius).

Related: Best Night Sky Events of April (Stargazing Maps)

Snaky stories

Tracing the long, slinky body of Hydra makes it clear why the ancient stargazers referred to these stars as a snake. Some authors refer to Hydra as a sea serpent, and not a few star guides have linked the constellation with the nine-headed swamp monster that Hercules killed by cauterizing each neck as he decapitated it. That beast, too, was known as Hydra. Some point out that when the constellation Hercules triumphantly appears high overhead on warm summer evenings, Hydra has all but slithered out of sight below the southwest horizon, with only the tip of its tail in view.

But the true origin of our celestial snake may be in Mesopotamia. Ed Krupp, director of the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, has pointed out that an engraved stone from the Seleucid period (312-64 B.C.) portrays the constellation Hydra as a serpentine monster. Leo, the lion, which lies above Hydra, marches upon the sea monster's back in the ancient drawing, just as happens in the sky. Older Babylonian star lists also include a serpent in these stars.

Hydra's head and nearby clusters

Hydra's head stands out well because it is located in a region of the sky relatively sparse in bright stars. This part of the constellation actually looks like the head of the celestial denizen it is supposed to portray.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Seen through a pair of wide-field binoculars, Hydra's head almost looks like a loose open-star cluster, thanks chiefly to several fainter stars. But in reality, this is just an illusion of perspective; these stars are all unrelated to each other. To the north of Hydra's head is the famous Beehive star cluster in Cancer, M44, which to the eye appears as a fuzzy patch of light — but with good binoculars, it immediately appears as a splattering of dozens of tiny stars. If you are blessed with a very dark sky, you can see the outlying members of the cluster spanning an area nearly three times the diameter of a full moon.

Midway between the Beehive and Hydra's head is the dense, open cluster M67, nicknamed the King Cobra cluster. In binoculars, the 500 or so stars that make up this cluster combine into a smooth, misty glow, but using a telescope equipped with a low-power eyepiece, you can pick out more than a few of the individual twinklers buried within it.

The star that's also a car

The brightest star in Hydra is Alphard, located to the lower left of Hydra's head. It's easy to spot, because it's a relatively bright, second-magnitude star, shining in a region of the sky where there are no stars of similar brightness, and it shines in a distinct orange color. It readily stands out and, for this reason, gets its name from the Arabic word for "the solitary one."

The Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe called this star Cor Hydrae, Latin for "heart of Hydra," though the Arabs insisted that it marked the backbone of the serpent. Alphard is a single, giant star, 50 times larger than our sun and three times more massive, located 177 light-years from Earth.

Interestingly, if you live in Asia, you may be driving a vehicle named for this star. The Alphard is a minivan that has been produced since 2002 by Toyota, primarily for the Japanese market.

Other automobiles have also been christened with star names. Most notably, there's the Chevrolet Vega (1970-1977), named for the brightest star in the constellation Lyra, and Subaru, the automobile-manufacturing division of the Japanese transportation conglomerate Subaru Corporation, derived from the Japanese name for the Pleiades star cluster.

Sooty star

One particular star in Hydra that is worth seeking out is U Hydrae, a rare carbon star. Such objects are the most strikingly colorful stars in the night sky. They are, like Betelgeuse and Antares, red giants, but they look even redder to the eye due to the relative abundance of carbon in their atmospheres. These carbon-rich molecules serve as a red filter, blocking out the shorter, blue wavelengths of a star's light.

Using the map above, scan with binoculars starting at the head of Hydra, then work your way down to Alphard near the center of the map. Then, carefully trace your way eastward (to the left) along Hydra's winding form. Use binoculars to locate U Hydrae, a star that cycles in brightness over approximately 450 days between magnitudes 4.7 and 5.2.

You'll know it when you see it; it appears as a deep-reddish-orange gem shining next to a pretty, curving row of fainter stars. If you defocus your binoculars slightly, it will make the dominant color more apparent.

The "other" water snake

Lastly, don't confuse Hydra with another celestial snake that has a similar name.

While exploring the Southern Hemisphere, two 16th century Dutch navigators, Frederick de Houtman and Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser, charted the stars located around the south celestial pole. From these observations, Petrus Plancius, a Dutch-Flemish astronomer, cartographer and clergyman, created a dozen new constellations, which first appeared on a celestial globe of his making in 1598. These star patterns were designed to fill otherwise undesignated space on the sky, and there is nothing distinguishable about any of them. But the rules of Latin tell us that Plancius' southern version of a water snake is male; its name is Hydrus.

In 1930 when the International Astronomical Union set forth the official boundaries for the 88 constellations, Hydrus somehow managed to make the cut.

I guess you can say he just slithered in.

- Hail Hydra! A Monstrous Constellation Explained

- Constellations: The Zodiac Constellation Names

- Full Moon Calendar: When to See the Next Full Moon

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Farmers' Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Verizon FiOS1 News in New York's lower Hudson Valley. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.