Editor's note: The Super Flower Blood Moon lunar eclipse thrilled stargazers around the world and has ended. See photos, video and more in our wrap story here.

This month's full moon — known as the Flower Moon — will undergo a total eclipse early on Wednesday morning (May 26), when it becomes completely immersed for a short while in Earth's shadow. But it also so happens that at that same time our natural satellite will be near that point in its orbit closest to Earth, which means we'll see a "supermoon" as well.

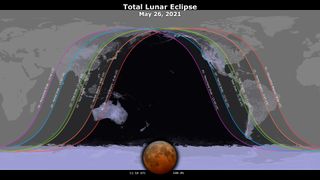

The lunar eclipse, which will be visible from Southeast Asia, Australia, New Zealand, the Pacific and the western part of the Americas, begins Wednesday at 4:47 a.m. EDT (0847 GMT) and will last about five hours from start to finish. The total phase of the eclipse, when the moon is covered in Earth's blood-red shadow, begins at 7:25 a.m. EDT (1125 GMT) and lasts 14 minutes 30 seconds.

Super Flower Blood Moon 2021: Where & when to see the supermoon eclipse Webcast info: How to watch the supermoon eclipse of 2021 online

If you take a photo of the 2021 total lunar eclipse let us know! You can send images and comments to spacephotos@space.com.

While the eclipse happens at the same time for everyone, whether you can see it — and how much of it you can see — depends on what time the moon rises and sets at your location (and, of course, the weather). The eastern U.S. will only see the beginning stages of the eclipse before moonset, but the West Coast will see all of totality, with the moon setting before the eclipse ends.

Check out the map and timetable below to find out when the eclipse is visible from your location, or try this interactive map by Time and Date. Also, be sure to check out Space.com's complete guide to the stages of the lunar eclipse.

Tuesday night (May 25) at 9:55 p.m. EDT (0155 May 26 GMT), the moon will arrive at perigee — that point in its orbit bringing it closest to Earth — a distance of 222,022 miles (357,311 kilometers) away.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

| Stage | ADT | EDT | CDT | MDT | PDT | AKDT | HST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penumbral eclipse begins | 5:47 | 4:47 | 3:47 | 2:47 | 1:47 | 12:47 | 10:47* |

| Moon enters umbra | — | 5:44 | 4:44 | 3:44 | 2:44 | 1:44 | 11:44* |

| Total eclipse begins | — | — | 6:11 | 5:11 | 4:11 | 3:11 | 1:11 |

| Maximum eclipse | — | — | 6:19 | 5:19 | 4:19 | 3:19 | 1:19 |

| Total eclipse ends | — | — | 6:25 | 5:25 | 4:25 | 3:25 | 1:25 |

| Moon leaves umbra | — | — | — | — | 5:52 | 4:52 | 2:52 |

| Moon leaves penumbra | — | — | — | — | — | 5:49 | 3:49 |

While circling Earth in an ellipse-shaped path, the moon comes to perigee once, occasionally twice a month, and the Earth-moon distance during these approaches vary by 3%. On Wednesday morning, a little over nine hours after the moon reaches perigee, at 7:14 a.m. EDT (1114 GMT), the moon will officially turn full and will also undergo an eclipse.

It will, in fact, be the biggest full moon in apparent size this year, popularly defined by many as a "supermoon." In contrast, on Dec. 18, the full moon will closely coincide with apogee, its farthest point from the earth. On that night the moon will appear 13.7% smaller than it will appear Wednesday morning.

Newsflash: A supermoon eclipse is really not so super!

Many websites are putting a special emphasis on the fact that this supermoon coincides with a total lunar eclipse — as if this makes the circumstances of this eclipse extra special. But actually, as far as a total eclipse is concerned, having a full moon so large and so close works against viewers by shortening the duration of totality, when the entire disk of the moon is covered with the Earth's dark inner shadow, called the umbra.

When the moon is closer to Earth, it moves in its orbit more rapidly than average. So, it is moving through the Earth's shadow at a quicker pace. In addition, during late spring and early summer, the diameter of Earth's shadow is at its smallest, all while trying to contain a larger-than-normal full moon.

And because this eclipse barely qualifies as a total one — the moon is tucked completely into the umbra with hardly any room to spare — totality will be unusually short: lasting less than 15 minutes.

Conversely, if the moon were near the apogee point of its orbit — colloquially known as a "micromoon" — it would appear smaller and move more slowly, thus helping to extend the duration of total phase of the eclipse by perhaps as much as 45 minutes!

Large tides

In addition, the near coincidence of Wednesday's full moon with perigee will result in a dramatically large range of high and low ocean tides.

The highest tides will not, however, coincide with the perigee moon but will actually lag by up to a day or so depending on the specific coastal location. For example, for New York City, high water (6.3 feet, or 1.9 meters) at The Battery comes at 9:02 p.m. EDT on Wednesday. From Cape Fear, North Carolina, the highest tide (5.5 feet, or 1.7 m) happens at 10:42 p.m. EDT on Wednesday, while at Boston Harbor a peak tide height of 12.2 feet (3.7 m) comes at 11:56 p.m. EDT on Wednesday. All three of these high tides occur 23 to 25 hours after perigee.

Any coastal storm at sea around this time would almost certainly aggravate coastal flooding problems. Such an extreme tide is known as a perigean spring tide, the word spring being derived from the German "springen" — to "spring up," and is not, as is often mistaken, a reference to the spring season. Spring tides occur when the moon is either at full or new phase. At these times the moon and sun form a line with the Earth, so their tidal effects add together (the sun exerts a little less than half the tidal force of the moon.) "Neap tides," on the other hand, occur when the moon is at first and last quarter phase and works at cross-purposes with the sun. At these times tides are weak.

Tidal force varies as the inverse cube of an object's distance. We have already noted that this month the moon is nearly 14% closer at perigee than at apogee. Therefore, it will exert 48% more tidal force at this full moon compared to the spring tides for the full apogee moon in December.

Huge moon at moonrise and moonset

Many astronomy books show comparison images of a full moon at perigee compared to a full moon at apogee. Placed side by side, the difference in apparent size is quite obvious. But usually the variation of the moon's distance is not readily apparent to observers viewing the moon directly in the actual sky.

Or is it?

When the perigee moon lies close to the horizon it can appear absolutely enormous. That is when the famous "moon illusion" combines with reality to produce a truly stunning view. For reasons not fully understood by astronomers or psychologists, a low-hanging moon looks incredibly large when hovering near to trees, buildings and other foreground objects. The fact that the moon will be much closer than usual this week will only serve to amplify this strange effect.

A perigee moon, either rising in the east at sunset or dropping down in the west at sunrise, might seem to make the moon look so close that it almost appears that you could touch it. You can see it for yourself by first noting the times for moonrise and moonset for your area.

Happy mooning — and for those who can see it, enjoy the eclipse!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.