Siberian wildfires double greenhouse gas emission record: This is how they look from space.

Wildfires in Siberia have emitted more carbon dioxide in two and half months than the world's sixth most polluting country emits in a year.

Wildfires in Siberia have produced 800 megatons of carbon dioxide since the beginning of June, nearly doubling last year's record, according to estimates by the European Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS).

In only two and a half months, the fires exceeded the annual carbon dioxide emissions of Germany, the most polluting European country. According to Climate Trade, Germany is the world's sixth worst polluter.

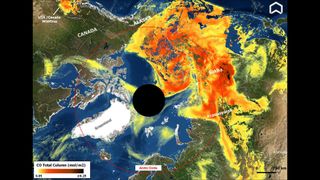

Satellites are keeping an eye on the fires as they devour the subpolar forest in the sparsely populated Russian northeast. Last week, they captured how the massive plume of smoke from the fires, over 4,000 miles long (6,437 kilometers), spread all the way to the North Pole and reached the coast of Alaska.

Related: The devastating wildfires of 2021 are breaking records

"Transport of smoke across the Arctic Ocean isn't in itself something unusual," Mark Parrington, senior scientist at CAMS, told Space.com in an email. "But to see such high values of different smoke constituents, aerosols and carbon monoxide, reaching the North Pole and then on to North America is reflecting the unusual scale and persistence of the number of fires and amount of smoke they have been producing this summer."

CAMS predicts that some of the soot from the plume will deposit within the Arctic Circle, which can worsen the melting of ice sheets. Parrington said that it is not easy to detect the soot in satellite images, but added that CAMS computer models indicate that some of the soot particles are indeed "raining" on the vulnerable sea ice.

"Deposition of dark colored aerosol particles onto white sea ice will alter the albedo [reflectiveness], reducing the ability of the ice to reflect solar radiation but rather absorbing it and accelerating the melting," Parrington said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Wildfires raging in North America are causing similar problems. CAMS models expect that particles from wildfires in the western U.S. and Canada will deposit in Greenland.

Siberia experienced a record-breaking fire season already in 2020, when many fires broke out inside the Arctic Circle. CAMS data, which go back to 2003, reveal a worsening trend.

"Fires in Siberia, like in many other places across the globe, are increasing in size and intensity," Federico Fierli, an atmospheric composition expert at the European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (EUMETSAT), said in a statement. "Although wildfires are regularly seen in Siberia at this time of year, it is becoming clear that their increasing scale is now the norm, rather than the exception — the trend is deeply concerning."

The fires, according to Parrington, destroy not only forests but also peatland, an important natural carbon sink, which will not easily recover its ability to store carbon after the blaze subsides.

Although estimates of the size of the area affected by the wildfires in Siberia vary, Moscow Times reported that, according to Greenpeace Russia, this year's fires might become the largest in recorded history. At least 178 active wildfires were reported in the Republic of Sakha, the most affected region of the Russian northeast, in the first week of August, according to NASA.

The good news is, according to Parrington, that latest images from Europe’s Sentinel satellites indicate that at least some of the fires might be easing off.

"Satellite imagery from the last few days has been showing reduced numbers of observed active fires," Parrington said. "There has also been a lot of cloud cover, which could mean that any continuing fires are not being observed, but in some areas as the cloud has moved, it seems as if the fires may no longer be burning."

#SATELLITE SPOTLIGHT: @NOAA's #GOES17🛰️ was tracking the explosive growth of the #CaldorFire last evening, seen here burning east of Sacramento, California. The #wildfire has grown to nearly 23,000 acres and thousands of people have been forced to evacuate. #CAwx pic.twitter.com/9LD0YI6mckAugust 18, 2021

The same is not true for western North America, where wildfires seem to have intensified over the past week. The devastating Dixie Fire, the largest in the history of California, continues ravaging the parched brushland and timber in the Sierra Nevada mountains, having destroyed about 570,000 acres (230,670 hectares) of land. On Saturday, the Caldor Fire erupted near Lake Tahoe, spreading at a rapid pace with the help of strong winds.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) today described on Twitter the Caldor Fire's growth as 'explosive', saying it has grown to nearly 23,000 acres.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.