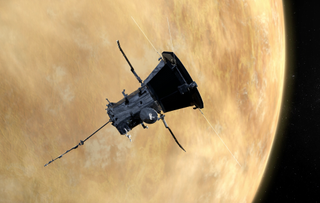

NASA's Parker Solar Probe has captured the first visible-light images of Venus

The visible-light imagery will tell scientists more about the geology and minerals of Venus.

In between its main mission, the Parker Solar Probe just made a novel contribution to Venusian science.

New images from the sun-focused mission, captured during a close flyby of Venus, show the planet in visible light for the first time. With time and analysis, the new images will provide valuable information about the planet's geology and minerals, NASA said.

"By combining the new images with previous ones, scientists now have a wider range of wavelengths to study, which can help identify what minerals are on the surface of the planet," the agency said in a statement Wednesday (Feb. 9).

"Such techniques have previously been used to study the surface of the moon," NASA continued. "Future missions will continue to expand this range of wavelengths, which will contribute to our understanding of habitable planets."

Related: What's inside the sun? A star tour from the inside out

The Wide-field Imager for Parker Solar Probe (WISPR) imaged the entire night side of the planet in visible light as well as infrared light, revealing regions including continents, plains and plateaus on the lava-soaked planet. Additionally, scientists spotted oxygen in Venus' atmosphere forming a halo around the planet.

Seeing the surface in visible light is no small feat, given that Venus is permanently shrouded by clouds. But it's not the first time WISPR took images of the planet, as it did so previously during a July 2020 flyby of Venus (the mission's third flyby).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

WISPR is designed to look at faint features on the sun and to pick up subtleties in the constant stream of particles flowing from the sun — known as the solar wind. It turns out these capabilities work well on Venus, not only showing its cloud tops but even peeking through to the surface, NASA said.

"Clouds obstruct most of the visible light coming from Venus' surface, but the very longest visible wavelengths, which border the near-infrared wavelengths, make it through," the agency explained. While the red light mostly gets lost in daylight pictures, the hope was that a nighttime pass would allow WISPR to see the heat of Venus glowing from the surface.

That chance came with a February 2021 flyby, the mission's fourth flyby of Venus, when the spacecraft passed by the planet's nightside for the first time.

"The surface of Venus, even on the nightside, is about 860 degrees Fahrenheit [460 degrees Celsius]," lead author Brian Wood, a physicist at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, said in the NASA statement. "It's so hot that the rocky surface of Venus is visibly glowing, like a piece of iron pulled from a forge."

WISPR picked up wavelengths ranging from the near-infrared (which was visible as heat) to the visible, between 470 nanometers and 800 nanometers. This work is distinctive from previous orbiting missions, which relied upon radar and infrared observations to look at the surface of the planet.

Notable past mapping efforts including the Soviet Venera 9 landing mission of 1975, NASA's Magellan mission that gathered the first planetary maps from orbit in the 1990s using radar wavelengths, and Japan's Akatsuki infrared images since reaching orbit around Venus in 2016.

WISPR's new images of areas such as the continental region Aphrodite Terra, the Tellus Regio plateau, and the Aino Planitia plains can be compared with these other mission images to gain more insights into the planet's history, NASA stated. Since Earth and Venus are both rocky planets, such studies may also help inform our understanding of rocky planet evolution more generally.

A study based on the research was published in Geophysical Research Letters on Feb. 9.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace