Challenge for astronomy: Megaconstellations becoming the new light pollution

The sky may brighten by a factor of two to three due to reflection of sunlight off megaconstellation satellites, a new report finds.

Satellite megaconstellations are quickly becoming a serious problem to 21st century astronomy akin to urban light pollution, and speedy action is needed as regulations considerably lag behind technology development, a new report finds.

The executive summary of the report, released last week by the American Astronomical Society (AAS), sums up the conclusions of a dedicated workshop called SATCON 2 that was held in July of this year.

The summary states that the industrialization of space, brought about by the advent of vast internet-beaming constellations of small and cheap satellites, such as SpaceX's Starlink project, is on the verge of transforming the appearance of the night sky.

Related: Astronomers ask UN committee to protect night skies from megaconstellations

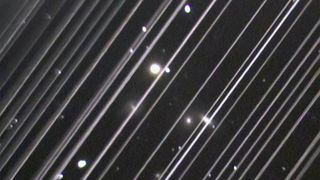

While most individual satellites are invisible to the naked eye, even the most basic telescopes will easily pick up their trails. Moreover, the sky may brighten by a factor of two to three due to diffuse reflection of sunlight off the spacecraft, further hampering observations, the report said.

The astronomical community, which found itself increasingly pushed out to remote uninhabited areas as cheap artificial lighting took over the world in the past century, is now facing a new, far less geographically restricted problem.

"About twenty years ago, rapid advances in technology led to the viability of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) as outdoor lighting," the report said. "With compelling operational and economic reasons to make the shift from legacy gas-discharge systems, communities around the world began installing white LEDs as their lighting of choice. In time, the side effects of the vastly increased sky glow and blue-rich spectral distribution of white LEDs became apparent."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The advent of LED outdoor lighting was so speedy that the unprepared astronomical community has been playing catchup ever since. With megaconstellations, the community now has a chance to affect the future course of events. That "window of opportunity," however, is closing quickly, the report said.

"We are on the threshold of fundamentally changing a natural resource that since our earliest ancestors has been a source of wonder, storytelling, discovery and understanding of ourselves and our origins," the report stated. "We transform that at our peril."

The report said that nearly all consulted SATCON 2 participants had already noticed a "dramatic rise in constellation satellite sightings" over the past two years, and some see the "unchecked actions of space actors as colonization expanded to a cosmic scale during a time of global crisis."

The report further added that the sky "must be considered part of the environment, and the current [U.S.] National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) exemption for the satellite constellation industry must end."

The participants named the relatively low pace of progress in terms of achieving academic consensus on such issues, and the further, even lengthier political negotiations as the major problems contributing to the situation. By contrast, the profit-driven satellite industry moves "quickly and nimbly, within the competitive environment of a new frontier of opportunity."

The report made basic recommendations for improved cooperation between the astronomy community and the industry but also discussed the importance of developing technologies that could protect astronomy from unwanted interference.

Improved satellite tracking, accessibility of this information in real time and software that masks and removes satellite trails from astronomical observations will be necessary, the report said.

The problem, the report stated, is not limited to optical astronomy but affects all wavelengths in which observations are conducted.

Astronomers were originally taken by surprise by the scale of the disruption caused by Starlink satellites, which became obvious shortly after the launch of the constellation's first big batch in 2019.

SpaceX tried to mitigate the problem by changing the altitude of the satellites and making them dimmer, but the success of these measures has been limited.

Human-made objects already interfere with astronomical discovery. Last year, for example, a team of researchers from China thought they had discovered a gamma ray burst, the most intense burst of light in the universe linked to a supernova explosion, coming from the oldest known galaxy in the universe. Later studies revealed that the intense brightening seen by the team was actually caused by a passing spent rocket stage.

The International Astronomical Union called on the United Nations earlier this year to protect the dark night sky as irreplaceable human heritage. The union announced in June this year that it intends to establish a Centre for the Protection of the Dark Sky from Satellite Constellation Interference that will focus on mitigation of optical light interference by satellite constellations.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.