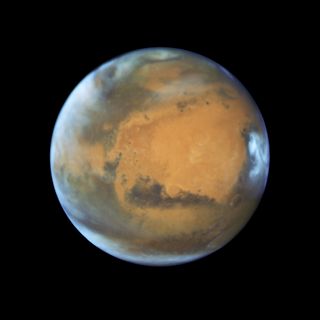

Chilly, damp Mars may have hosted an ancient ocean

Three billion years ago, the dusty planet we know today was a very different world.

A cold, wet Mars could have supported an ocean in the northern parts of the Red Planet three billion years ago, a new study finds.

New 3D climate simulations of the planet's ancient atmosphere and water suggest a liquid ocean once existed in the northern lowland basin of Mars. This ocean potentially persisted even when average global surface temperatures were below the freezing point of water, the peer-reviewed work suggests.

Although present-day Mars is cold and dry, decades of evidence suggests the ancient surface was covered with rivers, streams, ponds and lakes. Since water on Earth usually points to life, these old signs of water raise the possibility that the Red Planet was once home to life — and might host it still.

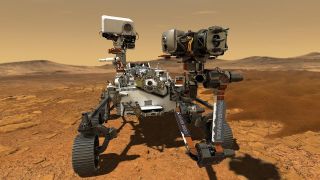

Earth and Mars potentially had similar climates about three billion years ago, when life was spreading on our planet. However, scientists debate whether Mars was temperate enough then to host an ocean of water, a question that could strongly influence whether the Red Planet was habitable enough to support life. Indeed, NASA's Perseverance rover mission is one of many sent to Mars to assess the planet's suitability for hosting ancient life.

Related: Water on Mars: Exploration & evidence

The new findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, published Monday (Jan. 17), contradict previous research suggesting Mars could not support such an ocean three billion years ago.

Relatively few branching river valleys that date to that time on Mars, for example, suggesting a lack of intense and widespread rainfall expected from a warm and wet climate.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But not all evidence points to a dry world; other evidence of contemporary tsunami debris argues against a Martian climate that was too cold and dry for an ocean.

The new study suggests a liquid northern ocean was possible because ocean circulation patterns may have warmed up the surface of that region up to 40.1 degrees Fahrenheit (4.5 degrees Celsius), well above water's freezing point.

More water was potentially in ample supply, too. The northern ocean could have experienced moderate rainfall within it, as well as near its shorelines. Another potential source was flowing glaciers from the southern highlands of the Red Planet, which hosted ice sheets.

An ocean-friendly Martian atmosphere looks somewhat like the carbon dioxide-filled version we see today, but with a twist: roughly 10% of the atmosphere was made up of 10% hydrogen gas, potentially getting released by volcanoes, cosmic impacts or chemical interactions between water and rock. (Today, by contrast, hydrogen is only present in trace amounts.)

This atmosphere combination of carbon dioxide and hydrogen could have trapped enough heat from the sun to keep surface temperatures warm enough for an ocean of liquid water, the study suggests.

It remains uncertain, however, whether this ocean could have supported life. "We are only studying the conditions where life could appear," study lead author Frédéric Schmidt, a planetary scientist at the University of Paris-Saclay, told Space.com. "A large standing body of water stable for a long time is important, probably necessary, but maybe not sufficient for life to appear."

Scientists are also unsure where the water went, Schmidt noted. Much of it could be frozen as ice under the surface of Mars, or chemically locked away in minerals. Solar radiation may have also broken water molecules apart into hydrogen and oxygen gas, with the hydrogen gas ultimately escaping into space, he added; NASA is tracking present-day Red Planet gas emissions through missions such as MAVEN (Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution Mission).

In the future, China's Zhurong rover (currently on Mars) — along with the planned ExoMars Rosalind Franklin rover from the European Space Agency and Russia's Roscosmos — could analyze the proposed boundary of this ancient ocean to confirm whether there was a shoreline and tsunami deposits there, the scientists said.

In the longer term, the proposed international Mars Ice Mapper mission could uncover additional signs of ancient seas on Mars, the team said. Future research may also explore what exact paths glaciers took to reach this ocean, to assist scientists in mapping geological evidence of glacial routes.

"For the moment, our simulation cannot predict that," Schmidt said.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us