One small piece of the Mars methane mystery may have just been solved.

NASA's Curiosity rover has spotted multiple surges of methane in Mars' air over the past few years — most recently in June, when levels of the gas inside the Red Planet's Gale Crater spiked to 21 parts per billion per unit volume (ppbv).

That's far higher than background methane levels on Gale's floor, which Curiosity has determined range seasonally from 0.24 ppbv to 0.65 ppbv.

Related: The Search for Life on Mars: A Photo Timeline

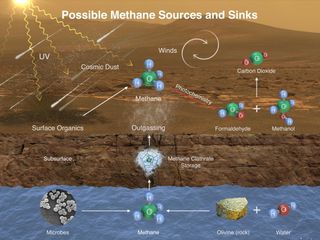

Scientists don't know what's producing this methane, or where exactly it's coming from. But they're keen to find out, because the gas is a possible sign of life. More than 90% of the methane in Earth's air, for example, was produced by microbes and other organisms.

A recent study may help researchers narrow the hunt. Scientists estimated the methane content of typical Red Planet rocks by analyzing Mars meteorites and native basalt and sedimentary rocks here on Earth — stand-ins for their Martian counterparts.

The team then calculated how much of this methane could be liberated by scouring winds, the dominant form of erosion on modern Mars. (The Red Planet hasn't hosted stable bodies of surface water for more than 3 billion years.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers determined that, for wind erosion to produce detectable levels of methane in the Martian air, the scoured rocks would have to contain as much methane as the most hydrocarbon-rich shale here on Earth. That's a very unlikely scenario, study team members said.

"What's important about this [finding] is that it strengthens the argument that the methane must be coming from a different source," co-author Jon Telling, a geochemist at Newcastle University in England, said in a statement. "Whether or not that's biological, we still don't know."

Indeed, methane can be produced abiotically as well — by reactions involving hot water and certain types of rock, for example. And it's unclear if the methane detected by Curiosity (and Europe's Mars Express orbiter, which confirmed one of the surges the rover found) is modern or ancient. However it was originally generated, the gas could have been trapped underground for billions of years before bubbling up to the surface.

The cause of the methane spikes is "still an open question," study lead author Emmal Safi, a postdoctoral researcher in the School of Natural and Environmental Sciences at Newcastle University, said in the same statement.

"Our paper is just a little part of a much bigger story," she added. "Ultimately, what we're trying to discover is if there's the possibility of life existing on planets other than our own, either living now or maybe life in the past that is now preserved as fossils or chemical signatures."

The recent paper was published in June in the journal Scientific Reports.

- Mars' Atmosphere: Composition, Climate & Weather

- 7 Biggest Mysteries of Mars

- Ancient Mars Could Have Supported Life (Photos)

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.