Extreme microbes in salty Arctic water could aid search for life on Mars

This harsh environment is one of Earth's closest analogues to Mars.

Never-before-seen microbes living deep beneath the permafrost at one of the coldest and saltiest water springs on Earth could provide a blueprint for life on Mars.

At Lost Hammer Spring, which lies above the Arctic Circle in Nunavut, Canada, briny water bubbles up through 2,000 feet (600 meters) of permafrost. The water has a salinity of about 24%, and the salt acts as an antifreeze to allow the water to remain liquid even at subzero temperatures. But it's the lack of free oxygen — less than 1 part per million — that makes the conditions there truly alien.

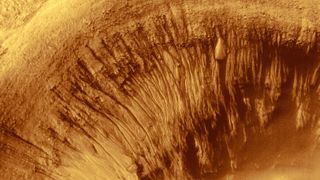

Indeed, the cold, salty and oxygen-free environment makes Lost Hammer Spring one of Earth's closest analogues to Mars, which has widespread salt deposits left by ancient water. And some researchers have argued that changes observed in gullies and dark streaks on the slopes of crater walls could have come from briny water welling up from underground, similar to the spring at Lost Hammer, although many scientists favor dry avalanches as perhaps a more likely explanation.

Related: How Martian microbes could survive in the salty puddles of the Red Planet

Now, a team of scientists has found microbial life in the extreme conditions of Lost Hammer Spring and has sequenced the genomes of about 110 organisms living there, revealing clues about how life could potentially survive in Mars' harsh environment.

Although microbes have been discovered in Mars-like conditions on Earth before, this is one of the first studies to find these "extremophiles" to be active in such an inhospitable environment.

"It took a couple of years of working with the sediment before we were able to successfully detect active microbial communities," Elisse Magnuson, a doctoral student at McGill University in Montreal and lead author of a new study describing the findings, said in a statement.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To survive the harsh conditions of Lost Hammer Spring, the microbes are anaerobic, meaning they don't breathe oxygen. Instead, to power their metabolisms, they consume methane and other inorganic compounds, such as carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, sulfate and sulfide, all of which are found on Mars.

In particular, the presence of methane on Mars is an unsolved mystery; scientists are divided on whether its origin is geological or biological. The sediment in the permafrost at Lost Hammer Spring continually emits gases incorporating methane and could provide a further clue as to the origin of the detected methane plumes on Mars.

"The microbes we found and described at Lost Hammer Spring are surprising because, unlike other organisms, they don't depend on organic material or oxygen to live," Lyle Whyte, who led the research team and is the Canada research chair in polar microbiology at McGill University, said in the statement. "They can also fix [i.e., convert into organic molecules] carbon dioxide and nitrogen gases from the atmosphere, all of which makes them highly adapted to both surviving and thriving in very extreme environments on Earth and beyond."

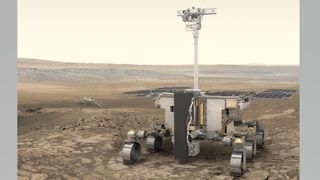

The results provide a genetic blueprint for how microbial life could survive — today or in the past — on Mars. The findings are so compelling that scientists working on the European Space Agency's delayed Rosalind Franklin ExoMars rover are testing its life-detection capabilities on samples of the microbes found at Lost Hammer Spring.

The findings were published April 8 in The ISME Journal.

Follow Keith Cooper on Twitter @21stCenturySETI. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.