Jupiter's rings may be so puny because of the planet's massive moons

For years, scientists have wondered why Jupiter doesn't have thick, bright rings like neighboring Saturn does, and now they think they might know why.

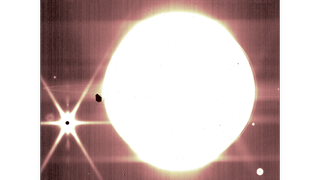

Though Jupiter does have faint, nebulous rings — as seen in recent images from the James Webb Space Telescope — they aren't nearly as prominent as those of Saturn or Uranus. In fact, they are so flimsy that they can't be seen with standard astronomical equipment. But now, using a sophisticated computer simulation, a team of scientists has discovered a possible explanation for why Jupiter's rings are not as prominent as its neighbors': Jupiter's moons may have prevented ice from settling around the massive planet.

"It's long bothered me why Jupiter doesn't have even more amazing rings that would put Saturn's to shame," Stephen Kane, an astrophysicist at the University of California, Riverside who led the research, said in a statement. "If Jupiter did have them, they'd appear even brighter to us, because the planet is so much closer than Saturn.

Photos: Saturn's glorious rings up close

"We didn't know these ephemeral rings existed until the Voyager spacecraft went past, because we couldn't see them," he added.

Kane wanted to figure out why Jupiter's rings are so faint and if the gas giant once had thicker rings and somehow lost them. To investigate these questions, he and his colleagues created a dynamical simulation that could take into account the orbit of Jupiter as well as the orbits of the planet's four main Galilean moons — Ganymede, Callisto, Io and Europa.

Saturn's rings are composed mainly of ice, some of which was delivered to the planet by comets , which are also made up mainly of ice. If moons orbiting a planet are massive enough, their gravity can cause ice to be ejected from orbit around that planet. These massive moons can also change the orbit of ice enough to cause this material to crash into them.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We found that the Galilean moons of Jupiter, one of which is the largest moon in our solar system [Ganymede], would very quickly destroy any large rings that might form," Kane said. "Massive planets form massive moons, which prevents them from having substantial rings."

The researchers' simulation has also led them to think it's unlikely that Jupiter had large rings at any time in its history.

Ring systems around planets aren't just beautiful; they can also be a useful way for astronomers to study the history of a planet and any collisions with moons or comets that it may have experienced. This is because the composition of the material in the rings and their shape and size give hints as to the events that created them.

The researchers now intend to use their simulations to study the ring system of Uranus. This investigation may reveal how long Uranus' rings will last and why it orbits the sun differently than the other planets in the solar system — the ice giant orbits the sun tipped on its side, and astronomers think this unusual tilt is the result of a collision with another body. Uranus' ring system could be the remnants of this impact.

"For us astronomers, they are the blood spatter on the walls of a crime scene," Kane said. "When we look at the rings of giant planets, it's evidence something catastrophic happened to put that material there."

The team's findings have been accepted for publication in The Planetary Science Journal, and a preprint version is available via the arXiv database.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.