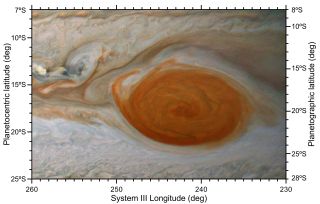

The most famous storm in the solar system is an apex predator.

Jupiter's Great Red Spot feasted on numerous smaller storms that wandered into its neighborhood recently, possibly even gaining sustenance from these meals, a new study suggests.

Astronomers have been observing the Great Red Spot continuously since the late 19th century. The storm has shrunk considerably during that stretch, going from 25,000 miles (40,000 kilometers) wide in the 1870s to about 10,000 miles (16,000 km) wide today. (For perspective: Earth is a little more than 7,900 miles, or 12,700 km, across.)

Related: Jupiter's Great Red Spot in photos

Astronomers aren't sure why the Great Red Spot is getting smaller. Some have speculated that collisions with smaller storms, which have increased in recent years, may play a role. The new study investigated that hypothesis.

Researchers led by Agustín Sánchez-Lavega, a professor of applied physics at the Basque Country University in Spain, studied images of the Great Red Spot captured between 2018 and 2020 by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, the space agency's Jupiter-orbiting Juno spacecraft and amateur astronomers here on Earth.

The team identified numerous encounters between the Great Red Spot and smaller anticyclones. (Anticyclones swirl around central cores of high atmospheric pressure, whereas cyclones such as Earth's hurricanes spin around regions of low pressure.) These atmospheric crashes chipped away at the Great Red Spot, peeling off cloud chunks around the big storm's edges.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Great Red Spot's diameter shrank as it gobbled up these smaller storms, the team found. But those changes were likely only skin-deep, "not affecting the full depth of the GRS [Great Red Spot]," Sánchez-Lavega and his colleagues wrote in the new study, which was published online Wednesday (March 17) in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

"The interactions are not necessarily destructive but can transfer energy to the GRS, maintaining it in a steady state and guaranteeing its long lifetime," they added.

"This group has done an extremely careful, very thorough job," Timothy Dowling, a professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Louisville who was not involved in the new study, said in a statement.

The flaking away of Great Red Spot material is likely just a surface phenomenon, leaving the storm's depths, which extend 125 miles (200 km) beneath Jupiter's cloud tops, largely untouched, Dowling added.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.