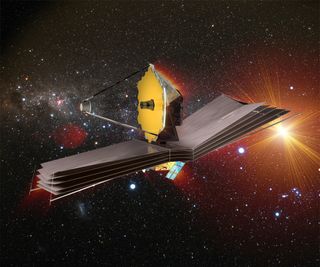

The James Webb Space Telescope is fully deployed. So what's next for the biggest observatory off Earth?

The generational observatory is en route to its parking spot and getting ready to test its mirrors and instruments.

Work for the James Webb Space Telescope is just beginning.

On Saturday (Jan. 8), the new observatory, the largest space telescope ever built, successfully unfolded its final primary mirror segment to cap what NASA has billed as one of its most complicated deployments in space ever. The Webb mission team is now turning its attention to directing the telescope to its final destination, while getting key parts of the observatory online for its astronomy work.

Webb is expected to arrive at its "insertion location" by Jan. 23, putting it in place to fire its engines to glide to a "parking spot" called Earth-sun Lagrange Point 2 (L2) about 930,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) away from our planet. If Webb gets to the right zone, it can use a minimum of fuel to stay in place thanks to a near-perfect alignment with the sun, Earth and moon.

But it's not just maneuvers in space that the control teams will need to execute. Webb still has a lot of complex commissioning operations ahead, and NASA particularly pointed to aligning its mirror and getting its instruments ready as key milestones to watch for in the next few weeks.

Live updates: NASA's James Webb Space Telescope mission

Related: How the James Webb Space Telescope works in pictures

As Webb prepares for the engine fire, team members will spend the next 15 days aligning the 18 mirror segments to "essentially perform as one mirror," John Durning, Webb's deputy project manager at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, told reporters Saturday (Jan. 8) in a press conference from Webb's control center at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland.

"I should say also, that Webb will start turning on the instruments in the next week or so," Durning added. "And then after we get into L2, as the instruments get cold enough, they [engineers] are going to be starting to turn on all the various instruments."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

L2 is an ideal location for Webb to perform its work. Thanks to the great distance from the sun and a sunshield, Webb will work in the darkness required for heat-seeking infrared observations. Infrared wavelengths will allow the telescope to peer through dust to look at objects such as young exoplanets, or the interior of distant galaxies, all on its quest to understand the universe and its evolution.

Related: Where is the James Webb Space Telescope? Here's how to track it.

Webb is equipped with four science instruments that will enable observations in visible, near-infrared and mid-infrared (0.6 to 28.5 micrometers) wavelengths, including a near-infrared camera, a near-infrared spectrograph, a mid-infrared instrument and a combination fine guidance sensor and spectrograph, according to NASA.

"Each instrument has their own set of milestones," Durning said. "That will be challenging to [calibrate] them once they reach temperature, making sure they get it all aligned.

Mirror deployment will start on Tuesday (Jan. 11), explained Lee Feinberg, Webb's optical telescope element manager at Goddard, in the press conference. The mirrors were folded for the stresses of launch and it will take somewhere between 10 and 12 days to "get all of the mirrors forward by roughly half an inch, and that puts them in a position where we can do the detailed optical alignment," Feinberg said.

Basic alignment will take about three months to get the them ready for "first light", when the telescope will take its first testing image as part of the alignment process. NASA warned those first images will most likely be blurry, since the telescope has not been fully aligned yet. It will take more imaging and testing to get the configuration right.

Related: The scientific mysteries that James Webb Space Telescope could unravel

"Right around day 120 is when we think the entire telescope will be aligned," Durning said, which would put the full alignment date around April 24, depending on how the commissioning process goes.

Instrument commissioning will be happening in parallel with the various instrument team partners, he added, who will be "turning on different instruments and ... then [will] use those instruments to align the telescope and to further refine the telescope."

There is a bit of historical sensitivity concerning blurry images from space telescopes, as the Hubble Space Telescope famously launched in 1990 with a sort of myopia that had to be corrected due to an engineering fault. Hubble works in low-Earth orbit, making it accessible to astronauts on the space shuttle for repairs and upgrades. Webb will be much too far away for such work and can only be calibrated through remote operations.

"We start with the mirrors off by millimeters and we're driving them to be aligned to within less than the size of a coronavirus, to tens of nanometers," Jane Rigby, Webb operations project scientist at Goddard, told reporters.

"It's this very deliberate process that is time consuming. Just so everybody knows, the first images that we take ... this telescope is not ready out of the box. The first images are going to be ugly. It's going to be blurry. We'll [have] 18 of these little images all over the sky, and we have to drive that into one telescope.

"I like to think of it as it's like we have 18 mirrors that are right now, little prima donnas, all doing their own thing, singing their own tune and whatever key they're in," Rigby continued. "We have to make them work like a chorus, and that is a methodical, laborious process."

As commissioning ends, Rigby said the team plans a set of "wow images" that are designed to show the telescope's capabilities. Those first targets have not yet been released to the media, but Rigby said the goal of these first pictures will be to "showcase all four science instruments and to really knock everybody's socks off."

The first images will include things such as stars (to check for precise alignment) and the Large Magellanic Cloud (to assess the telescope's ability to render shades of luminosity, or inherent brightness), officials said during the press conference.

Following commissioning (which will take about six months) will be a preliminary five-month science operations period made up of "early release science programs", with a set of six categories of work ranging from planet formation to stellar physics.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace