NASA's Voyager Missions Were Amazing. Now Scientists Want a True Interstellar Probe

Goodbye, heliosphere! Hello, interstellar space!

WASHINGTON — Humanity should consider building an interstellar probe to see our neighborhood from an outside point of view, argued several scientists at a recent conference.

NASA's Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft are the only machines that people have sent beyond our solar system. These 42-year-old spacecraft are still functioning well enough to send us information from interstellar space, and many of their insights have been surprising, according to Stamatios (Tom) Krimigis, the principal investigator of the low-energy charged particle experiment that is still working on both spacecraft.

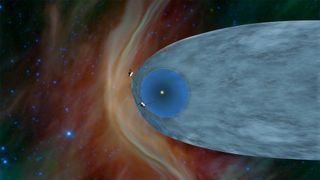

"The models have been wrong," Krimigis told delegates on Oct. 25 at the International Astronautical Congress held here. One prominent example was the shape of the heliosphere, or the region of space in which the stream of charged particles emanates from our sun and wraps around the solar system. Until the 2010s, scientists thought it had a fan shape; the Voyagers, upon crossing the heliosphere in 2012 and 2018, revealed it is more like a bubble.

Related: NASA's Voyager 2 Went Interstellar the Same Day a Solar Probe Touched the Sun

Another surprise was finding out where cosmic rays (radiation from outside the solar system) are accelerated, he said. Before the Voyagers went into interstellar space, scientists thought these particles accelerate at the termination shock area, which is where the particles from the sun slow down to below the speed of sound. The Voyagers revealed the acceleration actually takes place in the heliosheath, the region of space just beyond the termination shock zone.

Doing science en route

The Voyagers' heliosphere insights have been a lucky addition to their designated mission of exploring the giant planets. But building a tailor-made interstellar craft presents numerous technical challenges.

A daunting one is time. The Voyagers have been flying so long that second- and third-generation scientists and engineers are now part of their teams, and they must wrestle with aging hardware and computer software built in the 1970s.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Running spacecraft for decades is never a guarantee. Engineers generally build spacecraft to last for as long as scientists believe they will need to meet the mission's initial goals, typically two to three years, although many teams tweak designs with an eye to longevity. Spacecraft may break, fall silent or otherwise lose the ability to do science over time. Also, funding may cease as NASA or other agencies work on new science goals.

Leon Alkalai, who manages NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory's office of strategic planning and who spoke during the panel, suggested two programmatic options that could bring a mission to interstellar space fairly quickly, perhaps in a bit more than a decade.

Related: We Just Flew Past a Kuiper Belt Object. Here's Why We Should Do It Again.

Both options would use multiple flybys of planets to pick up speed. The slower option would use Jupiter for its main gravity assist, allowing scientists to obtain more detailed observations. The faster option would use the sun for its main gravity assist, giving speedy observations but in less detail.

To keep mission managers happy, Alkalai suggested an interstellar mission should be built to do science before it reaches its destination. The probe's ultimate goal would be to study interstellar space, but within the solar system, the spacecraft could, for example, image Kuiper Belt objects beyond Neptune or perform parallax measurements of small worlds to better calculate their distance. "There is plenty of science to do on the way on the interstellar medium," Alkalai said.

The solar system in context

A new interstellar mission would also represent a profound shift in the view of our solar system as a singular entity, because we would view the planets and sun from outside our sun's influence — as a passing alien might see our neighborhood. Insights we would gain include how the sun interacts with the gas and dust between stars, and how other stars interact with it as well, Robert Wimmer-Schweingruber, director at the Institute of Experimental and Applied Physics of the University of Kiel in Germany, said during the panel.

"There is a complex interaction between the [interstellar medium] and the solar wind, and our understanding is severely hampered by insufficient knowledge," he said. Even worlds nearer the boundary of interstellar space — such as Kuiper Belt objects — are poorly known in astronomy, providing a wealth of discovery potential, he added.

As the panel concluded, moderator Ralph McNutt, chief scientist of the space department at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, asked everyone born after 1990 to stand up. A third of the people in the room rose, and McNutt offered some career advice. He said that the standing-up group is the generation who would take over any interstellar missions launched by more experienced scientists today.

"When you are in that position, don't screw it up," he joked.

- Voyager at 40: 40 Photos from NASA's Epic 'Grand Tour' Mission

- What Spacecraft Will Enter Interstellar Space Next?

- Photos from NASA's Voyager 1 and 2 Probes

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace

Most Popular