Astronomers believe they’ve solved, at long last, a mystery first discovered nearly a decade ago by the Hubble Space Telescope.

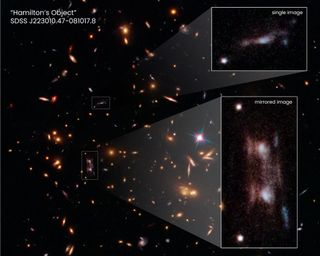

The dilemma centered on a strange "double galaxy," a pair of streaky objects that once defied explanation. Now, scientists think, the objects are actually one distant galaxy that appears as two thanks to a "ripple" in the fabric of space that is magnifying and distorting its image.

From Earth, the doubled objects almost 11 billion light-years away look like mirror images of each other. When astronomers first saw them in 2013, they immediately suspected a case of gravitational lensing — a phenomenon that occurs when light from a faraway object is warped, like an image through a fishbowl, by the gravity of something else between that object and the observer.

Related: The greatest Hubble Space Telescope of all time

That answered the how, but not the what or why. Hubble has glimpsed quite a few gravitationally lensed objects in its time, and this one was more than a mere warp. Gravitational lensing was somehow not just magnifying the galaxy but also copying it, creating two bright images, as well as a fainter third copy that can also be seen in the image.

After years of pondering the problem, astronomers have finally pinpointed the culprit: a large, uncatalogued cluster of galaxies sits between Hubble and the object, about 7 billion light-years from Earth. In addition, the lensed galaxy happens to sit upon a sort of ripple in space that's caused by the gravity of densely packed dark matter, the mysterious stuff that makes up about 85% of the matter in the universe.

The extra images were produced when light from the distant galaxy passed through the foreground cluster along this ripple, researchers said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Think of the rippled surface of a swimming pool on a sunny day, showing patterns of bright light on the bottom of the pool," Richard Griffiths, an astronomer at the University of Hawaii in Hilo, said in a statement.

"These bright patterns on the bottom are caused by a similar kind of effect as gravitational lensing," added Griffiths, lead author of a recent study announcing the results. "The ripples on the surface act as partial lenses and focus sunlight into bright squiggly patterns on the bottom."

The "ripple" could help astronomers better understand how dark matter is distributed throughout the universe, team members said. For example, by comparing the lensed Hubble images to computer models, the researchers determined that the dark matter in question likely wasn’t clumpy, but rather smoothly spread out.

"It's great that we only need two mirror images in order to get the scale of how clumpy or not dark matter can be at these positions," study co-author Jenny Wagner, an astronomer at Heidelberg University in Germany, said in the same statement.

The study appeared in the September issue of the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Rahul Rao is a graduate of New York University's SHERP and a freelance science writer, regularly covering physics, space, and infrastructure. His work has appeared in Gizmodo, Popular Science, Inverse, IEEE Spectrum, and Continuum. He enjoys riding trains for fun, and he has seen every surviving episode of Doctor Who. He holds a masters degree in science writing from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program (SHERP) and earned a bachelors degree from Vanderbilt University, where he studied English and physics.