Four ways to enjoy a solar eclipse

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Samantha Rolfe, Lecturer in Astrobiology and Principal Technical Officer at Bayfordbury Observatory, University of Hertfordshire

The kind of solar eclipses usually portrayed in films are total solar eclipses — a reasonably rare event. They’re likely what you think about when you hear the word "eclipse."

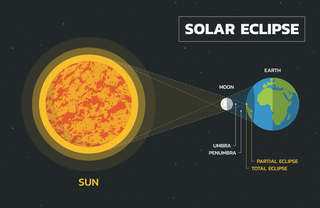

A total eclipse is when the moon and the sun line up in the sky in such a way that the moon blocks the entire face of the sun — called totality. Somewhere on the Earth these occur approximately every 18 months.

Related: 'Ring of fire' eclipse 2021: When, where and how to see the annular solar eclipse on June 10

But we can't all experience totality every time, as the shadow of the moon tracks a narrow path over the surface of the Earth. Any given point on the Earth is only likely to experience this approximately once every 375 years.

Being able to view a total solar eclipse strongly depends on your location and having cloudless skies (or at least patchy clouds). Even though totality is not very common, you'll likely have many partial solar eclipses from your location over the years. If you're lucky enough to be in the path of a total or partial eclipse, get prepared and know what to expect.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In the UK, we’ll get to see a partial eclipse on June 10, 2021. Here are a few suggestions of what to do during an eclipse.

1. Notice the moon blocking out the sun's light and heat

During any eclipse, the blocking of the sun's light and heat means it'll get darker and cooler. How dark and how cool depends on how much of the sun is being blocked. In a partial eclipse greater than 50%, enough light can be blocked to give the appearance of dusk.

This can confuse the local wildlife. You may notice the birds fall quiet, and bats might start to come out to feed, even though it could be the middle of the day.

Read more: Lunar and solar eclipses make animals do strange things

Depending on the time of year, you might want to bring a jumper or coat. The local temperature can drop several degrees. In 2001, a drop of 5 degrees Celsius (9 degrees Fahrenheit) occurred in Zambia during totality and in 1834 a 15 degrees Celsius (27 degrees Fahrenheit) difference was reported.

2. Test Einstein’s theory of relativity

Newton thought gravity was a force between two objects, but Einstein's 1915 theory of general relativity relied on the idea that gravity causes spacetime to bend. This means massive objects like stars cause the path of light to bend as it passes them by.

The sun is a massive object which, according to Einstein’s theory, would bend the light from distant stars as it passes in front of them. Normally the sun is far too bright to notice this light. But, in the few dark minutes of a total eclipse, you can see the stars near the sun.

Just over 100 years ago, a man called Arthur Eddington set up an expedition to two locations. One team went to the West African island of Príncipe, and the other went to Sobral, Brazil. Taking photographs of the eclipse from two locations allowed comparative measurements of the positions of stars to prove Einstein’s theory correct.

3. Think about our ancestors

Even if you didn’t know it was happening in advance, you wouldn't be concerned by a total eclipse of the sun. With our modern scientific understanding of the orbits of objects in our solar system, we'd understand why it was occurring. We can (and often do) let the many eclipses, especially partial ones, pass us by unnoticed.

Ancient scientists were conducting experiments about the size of the Earth, sun and moon around 2,000 years ago, experiments you can try yourself today. Our ancestors didn’t have our modern understanding.

As such, cultures from all around the world made up stories to explain what was happening. Historical solar eclipses have forced a truce between warring nations, scared a king to death and were generally regarded as omens.

4. Watch it happen — safely

We’re living in a time on this planet when the distance of the moon's orbit means that the apparent size of the sun and moon are approximately the same in the sky. The moon is very slowly moving away from the Earth, so total solar eclipses won't always be enjoyed by our descendants.

In the days leading up to the event, check the weather and note the time of the start, maximum point and end of the eclipse.

You can safely observe a partial or total eclipse of the sun with items from around the home — homemade pinhole cameras or even a kitchen colander can be used. Never look directly at the sun without specialist equipment, as it can cause permanent eye damage.

One strange thing we don’t understand during a total eclipse are shadow bands — lines of light and dark that appear on the ground just before an eclipse. If you are in the path of totality, you could try to record any evidence of them.

Taking even just a few minutes of your time to notice and enjoy these astronomical events can help you feel more connected to the wider environment and your place on planet Earth.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook and Twitter. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Most Popular