Cosmos: Possible Worlds' brings the search for E.T. down to Earth

In episodes 7 and 8 of "Cosmos: Possible Worlds," host Neil deGrasse Tyson explores themes of science as an instrument of hope and tenacity, and as a means by which the human race can realize its true potential.

Episode 7, titled "Search for Intelligent Life," focuses specifically on first contact and the search for intelligent life in the vastness of the cosmos. Are humans ready to make first contact with other intelligent beings? Is our technology even sophisticated enough to detect communication signals from another world?

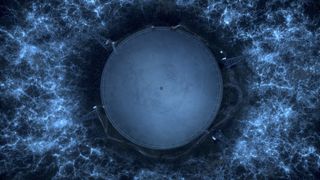

Seeking an answer, Tyson introduces us to China's Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope, or FAST, as it's more commonly known. FAST is the largest radio telescope on Earth and can detect radio waves across the universe.

Related: 20 sci-fi movies and TV shows to binge watch on Netflix right now

Tyson points out that we've only had the technology to detect radio signals for a little over a century, making FAST a truly monumental achievement. FAST has already detected a number of pulsars — or compact stellar corpses — and will continue to search for gravitational waves and signs of extraterrestrial intelligence, among other data it collects.

However, there's an intricate global communications network hidden here on Earth that we've only just become aware of. Tyson turns our attention to a "hidden matrix … the creation of an enduring collaboration among fungi, plants, bacteria and animals." He's referring to the mycelium, a complex network of threadlike filaments that forms the functional structure of a fungus and extends to other species, such as trees. These hauntingly beautiful hyphae, or the branching filaments that make up the mycelium, illustrated in the show by special effects to interweave in the soil beneath our feet, reveal the forests' complex and interlinked nature.

"Who are we to search for alien intelligence when we can't even recognize or respect the consciousness all around us, or even beneath our feet," Tyson says, strolling through the forest on top of the soil that's protecting the mycelium beneath his feet. Still, conversations with different worlds, Tyson says, will be done in the language of science.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The symbolic language of the scientist, mathematician and engineer avoid those things that are lost in translation from one culture to another," Tyson says, explaining that this type of language is more precise and less open to misinterpretation. If we find extraterrestrial intelligent life, will we be communicating with them in a language that resembles a computer programming language, built on the binary code?

"First contact" with intelligent life (on Earth)

Humans have actually already made "first contact" with other intelligent life that communicates through equations and a symbolic language, Tyson points out: bees. Insects in general have played an instrumental role in the development of the natural world, mostly by spreading pollen. Each grain of pollen has been"sculpted differently by evolution — each a novel strategy for survival, sharpened by vast expanses of time, " Tyson says.

Insects are as much a part of the Earth's history as the earth itself; The "great Ordovician biodiversity event," when our world began to change as plants and insects left the sea and began to make the land their home, occurred approximately 480 million years ago (or Dec. 20 on Tyson's "cosmic calendar," where the Big Bang marks New Year's Day). The world Tyson describes is an alien one; giant mushrooms tower over trees that only grew a few feet tall, and insects ruled the skies, undisturbed by other winged creatures.

It was Austrian ethologist Karl von Frisch who unlocked the secrets of bee behavior in the early 20th century. "For thousands of years, bees have been symbols of mindless industry … shackled to the dreary roles assigned to them by nature," says Tyson, but von Frisch found in his studies that bees lead much more complex lives. They communicate through mathematical equations expressed in their movements, appearing to the untrained eye to be little more than a waggle, but in reality can be an incredibly accurate set of coordinates to a food source meters away.

Tyson calls this a "first contact story" because bees and humans evolved on very different trajectories, and yet both species risked everything and chose the unknown; it's as if there were an unwritten code common to bees and human beings driving those ambitions.

This echoes the work of legendary scientist Charles Darwin, who realized if all life is related, certain philosophical implications had to follow. Darwin realized we are "surrounded by other ways of being alive and conscious," Tyson says, and that science had the potential to expand our capacity for empathy and compassion.

"The Sacrifice of Cassini"

Building on those themes of compassion and ambition, episode 8, "The Sacrifice of Cassini," chronicles tales of sacrifice and reveals the little-seen sentimentality and emotion that often accompany our greatest scientific endeavors. The episode honors the efforts and sacrifices of scientists Giovanni Cassini, Galileo Galilei, Christiaan Huygens, and Alexander Shargei, among others.

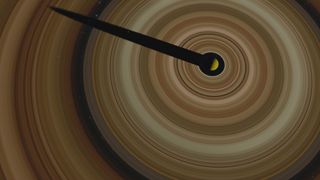

The episode opens with Tyson's recap of the Cassini-Huygens mission, a joint effort between NASA and the European Space Agency that launched Oct. 15, 1997. The spacecraft would embark on an epic voyage that would last more than two decades and culminate in a final, fatal mission of self-destruction by flying itself into Saturn's atmosphere in 2017.

Spacecraft sent to the outermost regions of our solar system, like Cassini, have brought back valuable data. Researchers are especially interested in any information about the mysterious ringed planets, which puzzled early planetary scientists like Galileo. These ring systems have been notoriously difficult to detect; Galileo's early research on Saturn had him believe the planet had two symmetrical moons, which we now know to be Saturn's rings. What would Galileo say if he could see Saturn as we see it now through the eyes of powerful scientific instruments?

NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft and Cassini also sent back valuable data about the atmospheres and other physical properties of our cosmic neighbors, like the elusive Uranus. Without Voyager 2, we wouldn't know about the planet's long summers and winters, or that while Uranus doesn't generate any internal heat and the outer edges of its atmosphere is hotter than 500 degrees Fahrenheit (260 degrees Celsius), Uranus also has the coldest clouds in the solar system, nearly 400 degrees Fahrenheit (240 degrees Celsius) below zero.

Interestingly, as Tyson reviews Giovanni Cassini's early life in what is now Italy, he notes that the Italian scientist began his career as an astrologer; a pseudoscientist. Louis XIV of France, the "Sun King," who would be the first monarch to recognize the power of science and the opportunities it afforded national security, would play a pivotal role in Cassini's career development. It was Louis XIV, who established the Paris Observatory — a scientific powerhouse — and who gave Cassini the tools he needed to pursue his research.

Cassini's observations of Saturn and its moons would have an enduring effect on the scientific world among his other accomplishments, like having discovered Jupiter's Great Red Spot (independently from Robert Hooke) and having calculated the length of a day on Mars; he was only off by 3 minutes.

Cassini's work on Saturn also greatly furthered human beings' knowledge on the planet at the time; he was the first to know Saturn's rings were composed of natural satellites orbiting the planet, and that there were gaps between them. Decades later, a bus-size 12,000-lb. (5,400 kilograms) spacecraft, sent on a years-long voyage to that same celestial body, would be named in his memory.

The scientists who worked closely with the Cassini-Huygens spacecraft, some of them since the very beginning, undoubtedly became emotional as it completed its final mission, as did spectators around the world who witnessed its final moments.

The probe's travails, however, cannot compare to the pain and tragedy of scientist and visionary Oleksandr Shargei, a forgotten pioneer of spaceflight. Shargei was orphaned at a young age and, while studying engineering at a university in Saint Petersburg, Russia, was drafted to the army to serve the Russian Empire in World War I. After the Russian Revolution, when the Bolsheviks overthrew the government, he changed his name to Yuri Kondratyuk out of fear for his life.

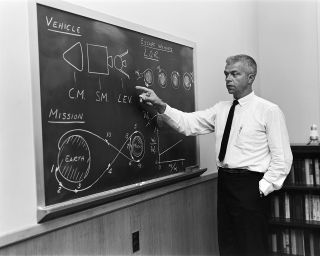

In 1926, Kondratyuk self-published a manuscript on rocket motion and space colonization, which would end up capturing the attention of an engineer working on the Apollo program, John Houbolt, decades later. Houbolt's updating of Kondratyuk's theories convinced NASA to select the lunar orbit rendezvous flight plan for Apollo, and to win the Space Race.

Seeing footage from Apollo 11 in the episode elicits a sentimental feeling as it dawns on us that we're witnessing Kondratyuk's dreams become reality, and that his dreams are still coming true to this day; even the Cassini mission used gravity assist maneuvers, also conceived by Kondratyuk, to explore the Saturn system.

The final scene of the episode is of Kondratyuk's childhood home — a place where he endured much tragedy in his early years, and sought refuge in physics books. It was also here that Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong made a pilgrimage after his historic flight to the moon, to honor the man who made that voyage possible.

"There are all kinds of stories in the struggle to understand the cosmos," Tyson reflects. "Sometimes your dreams die with you, but sometimes the scientists of another age pick them up and take them to the moon, and far beyond."

"Cosmos" airs on the National Geographic channel on Mondays at 8 p.m. ET/9 p.m. CT and will be reprised on the Fox television network this summer.

- 'Cosmos: Possible Worlds' episode 5 explores the 'cosmic connectome'

- 'I want the solar system to become our backyard,' Neil deGrasse Tyson says

- Carl Sagan: Cosmos, Pale Blue Dot & famous quotes

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save at least 56% with our latest magazine deal!

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.