Here's what we know about planetary protection on China's Tianwen-1 Mars mission

NASA can't formally ask its counterpart what protections are in place.

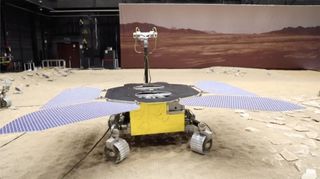

This spring, China will attempt its first Mars landing. But in anticipation of that milestone, scientists are wondering whether the Tianwen-1 rover may carry Earthly contamination with it to the surface.

Because scientists have high hopes of someday discovering traces of life on Mars, spacecraft that will land on the planet are kept as immaculately free of Earthly life as possible. These days, that means a complicated cleaning procedure throughout the spacecraft's assembly and frequent testing for spores, an inactive form of bacteria that are particularly hardy.

NASA's Perseverance rover went through precisely that treatment before it left Earth in July for its journey to Mars. However, Congress bans NASA from communicating with its Chinese counterpart.

"I don't know anything beyond what all the rest of us know from the public releases of information, but they do participate," Lisa Pratt, NASA's planetary protection officer, told a virtual meeting of the committee leading the creation of a new decadal survey identifying the priorities of planetary scientists into the 2030s on Feb. 11.

Related: China's Tianwen-1 Mars mission in photos

If the Tianwen-1 mission successfully touches down on Mars, China will become only the second country to operate a spacecraft on the Red Planet's surface, joining NASA. (The Soviet Union and the European Space Agency have had spacecraft on the surface, but these missions either crashed or failed in less than a minute.)

Like the U.S., China is party to the Outer Space Treaty, established in 1967, which outlines what nations can and cannot do in outer space — yes to working for all humanity, no to nuclear weapons, for example. One tenet of the Outer Space Treaty refers to planetary protection, stating that countries must explore other worlds "so as to avoid their harmful contamination."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

There are a few reasons to be wary of bringing terrestrial bugs to other worlds. For one, scientists don't want any Earth creatures to be able to make a home for themselves on Mars; for another, scientists want to be confident that if they detect traces of life on Mars, that sign is indeed from Mars, not some wayward fingerprint that came from Earth.

According to previous reporting by Space.com, Tianwen-1 is targeting a landing in Utopia Planitia, at a site where there's no evidence of water ice near the surface. (When it comes to planetary protection, sites with water are always scientists' top concern.) Long ago, however, there may have been ancient groundwater deep below the surface and mudflows in Tianwen-1's landing zone.

NASA's Viking 2 and InSight landers both touched down elsewhere in this same region. The twin Viking landers were the first spacecraft that NASA engineers sampled before departure, archiving organic and biological material from them so that if instruments detected a potential signal of life, scientists could compare such data to the samples remaining on Earth.

Launched in the 1970s, the Viking mission still predated NASA's earnest planetary protection standards for Mars. But InSight landed in 2018 and was required to meet specific standards before launch of just how dirty the spacecraft could be, with engineers searching for and tallying exposed surfaces in the spacecraft for spores.

Spore-counting is a standard NASA would like to move away from, as it turns out, but potential future techniques, including those relying on genetic analysis, aren't ready yet, Pratt said. So spores it is. And China is likely in the same place, Pratt said, noting that Chinese scientists do have contacts with a key Italian planetary protection team, so should be aware of current standards.

However, while NASA and its Chinese counterpart can't interact directly, sometimes their representatives end up at the same meetings, and Pratt told the story of just such an occasion, which she attributed to November, when she ended up seated next to a Chinese scientists.

"I asked a question in front of everybody, I said, 'Can you talk to us about what you did for planetary protection compliance?'" Pratt told the committee. "And the individual sort of said, 'We did what all the rest of you do, we did the spore metric measurements, and we were highly compliant.'"

NASA, however, hasn't seen those measurements and may never.

"They at least said the right thing. Needless to say, there is no inspection, no external verification," Pratt said. "At the moment, my thought is, 'OK, I'm taking their word for it,' because I don't have any way to know otherwise."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.

Most Popular