'Oumuamua and Borisov Are Just the Beginning of an Interstellar Object Bonanza

Astronomers are only now getting the hang of spotting interstellar objects, space debris that fled another solar system to swing through ours. But signs suggest there should be plenty more such identifications to come.

That's the conclusion of new research that was already in the publication process when scientists met the second known interstellar object, a comet called Borisov, which was first spotted on Aug. 30. The research looks ahead to a new instrument, the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST), which is scheduled to be fully up and running in 2023. The scientists estimate that each year it's working, LSST should be able to spot more than 100 interstellar objects larger than 6 feet (2 meters).

"There should be a lot of this material floating around," Malena Rice, lead author of the new research and a graduate student at Yale University, said in a statement. "So much more data will be coming out soon, thanks to new telescopes coming online. We won't have to speculate."

Related: Interstellar Comet: Here's Why It's Got Scientists So Pumped Up

Ever since they first spotted 'Oumuamua in October 2017, astronomers have suspected that the detection was a clue that there are more interstellar objects passing through our solar system than previously expected. The coincidence of the new research is that the two authors had just finished writing up the study when the interstellar comet Borisov entered the scene, according to the same statement.

That coincidence means that the research is based exclusively on observations of 'Oumuamua, which scientists were able to watch for only a week or so. (Borisov will remain observable for a year, offering astronomers an abundance of data.)

The new research tackles the question of how these interstellar objects begin their long journey. One possible origin story was that 'Oumuamua and its presumed compatriots were planetesimals, the building blocks of planets, kicked out of their native solar systems. But Rice and her co-author think that explanation doesn't quite do the trick.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

That's based on what scientists know about other solar systems through the more than 4,000 exoplanets identified to date. That's not necessarily a representative sampling, since astronomers have only a handful of techniques for spotting exoplanets.

But Rice and her co-author found it suspicious that most of the planets astronomers have spotted to date aren't the sort of planets that should be able to kick out planetesimals. They argue that such dynamics would have to be triggered by planets as massive as Neptune or larger and that orbit at least five times farther from their star than Earth does the sun.

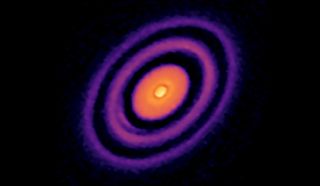

That's exactly the sort of world that astronomers are still struggling to identify from Earth. So the researchers turned to a project called the Disk Substructures at High Angular Resolution Project, which surveyed 20 young solar systems close enough to Earth that the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array telescope in Chile could get a decent picture of them.

Some of these disks sport gaps that mark where a forming planet has cleared a swath of debris. That tells scientists what size planets are forming and how close they are to the star. So the researchers took three of those systems and modeled how likely it would be that their planets can kick out planetesimals on a dramatic tour of the universe.

"This idea nicely explains the high density of these objects drifting in interstellar space," Gregory Laughlin, an astronomer at Yale University and Rice's co-author, said in the same statement. "It shows that we should be finding up to hundreds of these objects with upcoming surveys."

And of all the upcoming observation programs, LSST is the most intriguing when it comes to spotting interstellar objects. After the lag between recognizing 'Oumuamua and any additional visitors to our solar system, astronomers had begun to suspect that they may not spot another interstellar object until LSST is turned on, Karen Meech, an astronomer at the University of Hawaii who has observed both 'Oumuamua and the new interstellar comet, told Space.com earlier this month.

It was just when her team had given up hope that Borisov arrived on the scene, with a stunning icy blanket marking it as a clear comet, and early enough in its journey that astronomers will be able to study it for a year. That's an incredible benefit to scientists.

"You're not looking at a distant star through a telescope," Rice said in the statement. "This is actual material that makes up planets in other solar systems, being flung at us. It's a completely unprecedented way to study extrasolar systems up close — and this field is going to start exploding with data, very soon."

The research is described in a paper posted to the preprint server arXiv.org on Sept. 13 and accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

- We Could Chase Down Interstellar Comet Borisov by 2045

- This Comet Might Be from Interstellar Space. Here's How We Could Find Out.

- 1st Color Photo of Interstellar Comet Reveals Its Fuzzy Tail

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.