The International Space Station (ISS) won't be the only off-Earth outpost for much longer, if all goes according to plan.

Yesterday (Nov. 2), the huge orbiting laboratory celebrated 20 years of continuous human occupation, a big milestone in humanity's push to extend its footprint into the final frontier.

The ISS — a collaboration among the United States, Russia, Canada, Japan and the participating nations of the European Space Agency (ESA) — still has considerable life left: It's officially approved to operate through December 2024, and an extension to the end of 2028 seems likely. And whenever the station's race turns out to be run, several other projects are poised to take the baton.

Related: How the International Space Station will die

For example, Houston-based company Axiom Space plans to use the ISS as a jumping-off point for its own station in low Earth orbit (LEO).

Axiom aims to start launching new commercial modules to the ISS in 2024, to provide more living and research space for astronauts aboard the orbiting lab. And, when the ISS is retired, "Axiom Station will complete construction and detach to operate into the future as a free-flying complex for living and working in space — marking humankind's next stage of LEO settlement," Axiom representatives wrote on the company's website.

Axiom will also provide other services, including purchasing tourist flights to the ISS aboard SpaceX Crew Dragon capsules. Axiom has already signed a contract with SpaceX to this effect, and the first of those private missions is expected to launch late next year.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

California-based Orion Span has plans for its own LEO station called Aurora, which the startup says could launch in late 2021 and begin accommodating customers the next year. Funding uncertainty may complicate the company's aims, however. (Another company, Bigelow Aerospace, has long been planning to set up private outposts in orbit and on the moon. But Bigelow laid off its entire workforce this past March.)

Then there are the government space stations. China wants to build a LEO outpost that's roughly the size of the Soviet-Russian station Mir, which was intentionally de-orbited in March 2001. (Mir was about one-quarter the size of the ISS, which is about as long as a football field.)

China wants to start assembling its station in the next year or so. The nation has already made considerable strides in this direction: Since 2011, China has launched two prototype habitat modules to orbit and sent astronauts to both of them, as well as a robotic resupply ship to the second one.

India also wants its own LEO outpost. The nation is working to launch its first crewed mission to orbit in 2022, the 75th anniversary of Indian independence from the United Kingdom. That milestone launch will help pave the way for a space station, which will be up and running by 2030, if all goes according to plan.

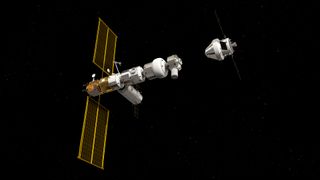

And humanity will push beyond LEO in the coming years as well. NASA plans to start building a small moon-orbiting space station called Gateway as part of its ambitious Artemis program of crewed lunar exploration.

Gateway's core — a habitat module and a power and propulsion element — are scheduled to launch together in late 2023, and a few other pieces will likely join the outpost later. Gateway will serve as a staging point for crewed and uncrewed jaunts to the lunar surface, NASA officials have said.

Related: How to build a lunar colony (infographic)

The Artemis program aims to put two astronauts down near the moon's south pole in 2024 (a landing that will likely not make use of Gateway). But NASA wants the program to do much more as well — specifically, establish a long-lasting, sustainable human presence on and around the moon by 2028.

So we could see an outpost take shape on, or slightly beneath, the lunar surface by the end of the decade. And NASA would probably not build such infrastructure by itself; ESA has long suggested getting a "moon village" up and running, and multiple private companies have expressed interest in helping extract and sell lunar resources such as water ice.

Another key Artemis goal is to help pave the way for crewed missions to Mars, which NASA wants to start launching in the 2030s. Those initial flights could lead to a research outpost on the Red Planet, a base from which scientists could hunt for signs of Martian life and perform a range of other experiments.

And we could see a bona fide city start to rise from the red dirt in that same general timeframe, if SpaceX's plans come to fruition. The company, which Elon Musk founded in 2002 primarily to make humanity a multiplanetary species, is already test-flying prototypes of Starship, the next-generation vehicle designed to take people to the moon, Mars and other distant destinations.

If Starship development goes well, the spacecraft will likely be able to start flying passengers to the Red Planet within 10 years, SpaceX president and chief operating officer Gwynne Shotwell said recently.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.