Once Upon a Time on Ryugu: Asteroid Features (and Its Boulders) Get Storybook Names

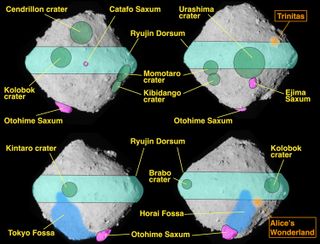

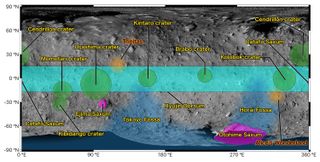

The Hayabusa-2 team has introduced fanciful new names for the features found at the top-shaped asteroid Ryugu, including the first-ever outer-space boulders to get official names.

The new names were approved in December 2018 by the International Astronomical Union's (IAU) Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature, according to a new blog post from the team.

Hayabusa-2 arrived at Ryugu in late June 2018 and has since extensively photographed its surface and dropped a hopping lander and minirovers on the object. Ryugu itself is named for a dragon's palace in a Japanese children's story, and the rest of the features' official names follow that children's story theme. [Visions of Ryugu: The Funny (and Scary) Asteroid Predictions by Japan's Hayabusa-2 Team]

The researchers also proposed a new category of feature for recognition — one whose presence has a huge effect on Ryugu's surface: the boulder, which in IAU parlance can now be called a "saxum."

"Numerous boulders are distributed on the surface of Ryugu," researchers wrote in the blog post. "Regardless of where you look, there are rocks, rocks and more rocks. This is a major characteristic of Ryugu and continues to make plans for the touchdown operation of the spacecraft difficult."

"However, there was no precedent for boulder nomenclature and even the name type did not exist (during the exploration of the first Hayabusa mission, naming the huge boulder protruding from asteroid Itokawa was not allowed)," they added.

One particular rock at Ryugu's south pole, which will now be called Otohime saxum, has already piqued researchers' interest because of its immense size and evidence that it has a different composition from its surroundings. This rock and others led the group to petition the IAU to create a new class of feature for boulders with certain characteristics. The other features on Ryugu fall under classes like "crater" (like those familiarly found on the moon), "dorsum" (peak or ridge) and "fossa" (grooves or trenches), researchers said in the blog post.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

All names of features on astronomical bodies share a theme, and in this case, the team considered names of castles around the world, words for "dragon" in different languages and names of deep-sea creatures before settling on "names that appear in stories for children."

Many of the official names are drawn from the same story as "Ryugu" itself, including the princess who lived in Ryugu castle and her father, a dragon god; the fisherman who saves a turtle; the turtle; and three locations from the story — read the blog post for much more detail and a full list of names. Other names draw from Japanese, French, Russian, Dutch and Cajun folktales. Proposed names "Peter Pan" and "Sleeping Beauty," were rejected due to copyright issues and length, respectively, according to the post.

As the Hayabusa-2 mission continues, researchers will continue to propose names for the fantastical features it finds.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.