Wild 'Tunnelbot' Designs Could Crack Secrets of Icy Jupiter Moon Europa

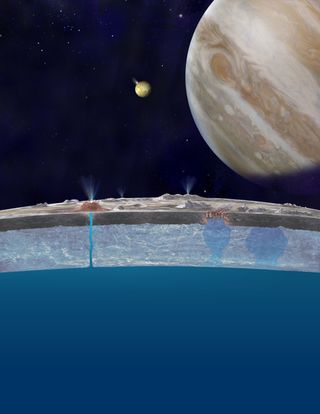

The icy shell encasing Jupiter's moon Europa is both a promise and a problem: It increases the plausibility of life floating through the ocean that scientists think hides below it by blocking damaging radiation, but it also blocks scientists from getting a good look at what's going on under the ice.

That's why scientists have begun to dream up specialized probes that would carry instruments below the ice. Andrew Dombard, a geophysicist at the University of Illinois at Chicago, is one of those scientists, and he presented two possible designs for a "tunnelbot" at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union last week.

"Every time you propose a new, kind of zany idea, people are like, 'Really, can you make this work?'" Dombard said. "We think we can." [Photos: Europa, Mysterious Icy Moon of Jupiter]

The team premised their work on the assumption that by the time the tunnelbot was ready for its journey, they could bring some sort of station to set up on Europa's surface that could survive for the three years or so the tunnelbot would take to burrow through the icy shell. That's a big requirement: NASA's next planned mission to the moon will only orbit Europa, and even if the much-discussed Europa Lander mission concept becomes a reality, the lander would last just three weeks.

But there were plenty of constraints to take into account in the design process. One such constraint was developing a probe that would collect solid ice samples for scientists to analyze. "In order to do this right, we need to get solid ice samples as we're going through the ice shell, and of course we're melting on the way down," Dombard said. "It would be a lot easier to bring in some of the meltwater, but from the scientific standpoint that is certainly not preferred." Instead, scientists would want to be able to melt the ice in a carefully controlled environment where they could measure the gases that were trapped inside it.

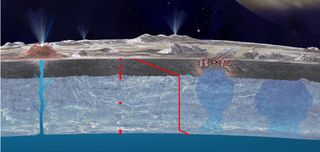

The team also had to factor in a major uncertainty about Europa: No one knows just how thick its icy shell is. Because the team wants to be sure to burrow all the way through the ice, that means they don't know how far the tunnelbot needs to be able to move. So Dombard and his colleagues worked with a fairly conservative estimate, figuring the tunnelbot would need to travel up to about 12.5 miles (20 kilometers) down through the shell.

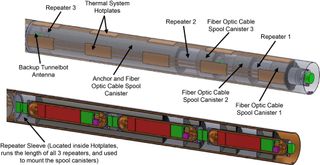

Another challenge is sending data back to Earth, which traditionally relies on radio waves. But Dombard and his colleagues think that the ice shell may weaken the signal too much for safe operation. So they also designed a relay system that would deploy every 3 miles (5 km) and rely on a fiber-optic cable.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But for Dombard, who used to work at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, which has built spacecraft like the Parker Solar Probe and New Horizons, these sorts of constraints were intellectually intriguing.

"This was kind of a little bit of a homecoming for me. … It was nice to get my hands dirty with a little mission work," he said. "It's fun working with the data once you have the data, but there's a certain satisfaction that goes into, well, how do we get the data in the first place?" [Water Plumes on Europa: The Discovery in Images]

Dombard and his team worked through two different theoretical probe designs that could burrow through the ice, taking measurements as it went, then park itself, poking into the subsurface ocean to gather still more data. "I think that would be really exciting, to get a picture back from the bottom of Europa's ice shell," Dombard said.

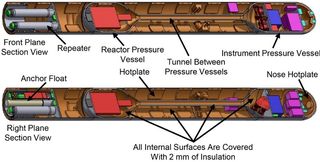

The first design uses General Purpose Heat Source bricks, which are powered by radioactive plutonium. That fuel source allows for a simpler design, and a lighter probe to carry to the moon. But it also produces less heat, which means it can't melt quite as large of a tunnel. That means in order to make this design work, the probe must be about 10 inches (25 centimeters) wide — which means some of the instruments required to study the ice and the ocean below it will need to be streamlined.

"Jamming a microwave into a sewer pipe is a bit of a challenge," Dombard said, using an analogy for the size problem. "You'd have to redesign the microwave to be able to do that."

The second design, powered by a nuclear reactor, avoids that problem — it lets off much more heat, so the probe can be about twice as wide. But this fuel source brings its own challenges, in particular, protecting the probe from radiation. Dombard and his team solved this problem by leaving half of the 16 feet (5 meters) of the probe's length empty. Once the probe arrives on Europa, it would melt some local ice to fill that chamber, shielding the instruments.

Of course, there's another major hurdle the team didn't even try to address: funding the massive cost of such a mission.

"I would personally love to see this happen, but it will require a fair amount of money to make it happen," Dombard said. "I told people at the conference [of the American Geophysical Union last week, where he presented the designs] to start saving their nickels, or maybe have a bake sale or two."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom and Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.

Most Popular