The Human Fossil-Fuel Addiction: Greenhouse Emissions Soar to Record Levels

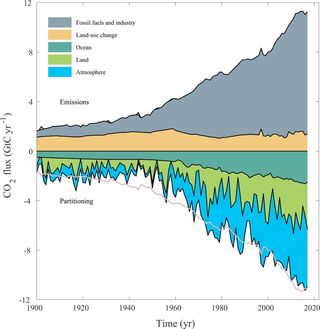

After a few promising years of minimal carbon-emission growth, the world is on pace to burn a bunch more fossil fuels. According to a new estimate, global carbon emissions will hit a record-breaking 37.1 billion metric tons in 2018.

That's a 2.7 percent increase over 2017's global emissions output of 36.2 billion metric tons, researchers with the Global Carbon Project reported Dec. 5. And 2017's numbers represented a 1.6 percent increase over the year before.

"For three years, we saw flat greenhouse gas emissions at the same time [that] the world economy grew. That was good news," said Robert Jackson, a professor of Earth system science at Stanford University. "We hoped that represented peak emissions. It didn't." [The Reality of Climate Change: 10 Myths Busted]

To turn off the emissions spigot, countries will have to focus on renewable energy, and quickly, Jackson said.

Rising emissions

Climate change is already underway. A 2010 NASA study found that Earth's average surface temperature rose 1.44 degrees Fahrenheit (0.8 degrees Celsius) over the 20th century. The Arctic, in particular, is responding rapidly to this change, exhibiting record levels of melt. Surface meltwater from Greenland alone now contributes nearly a millimeter of global sea-level rise to the oceans each year.

In October, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned that the world will have to slash carbon emissions to 45 percent below 2010 levels by the year 2030 and then halt all emissions by 2050 in order to keep global average temperatures from rising more than 2.7 degrees F (1.5 degrees C).

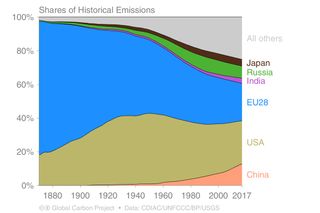

Currently, emissions are headed in the wrong direction, Jackson and his team found. Between 2017 and 2018, China is estimated to have increased its carbon output by 4.7 percent. The U.S. output has risen about 2.5 percent in the same period. India saw the sharpest increase in carbon output between 2017 and 2018, at an estimated 6.3 percent. The European Union has increased its outputs as well, by 0.7 percent.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The drivers of these trends are both meteorological and economic, the researchers reported. An especially cold winter in the eastern United States and a hot summer across the country increased fossil fuel emissions from the heating and cooling of homes and other structures. A decline in the price of oil led to the purchase of larger cars and trucks in the United States. Meanwhile, a sluggish economy in China has leaders there incentivizing heavy industry and instituting coal-power projects that had been on hold, Jackson said. Economic development in India has that nation scrambling to build any energy project it can.

"They're building coal, nuclear and renewables at breakneck pace," Jackson said. "Every coal plant they build is likely to be polluting 40 years from now."

Turning it around

Despite the sobering trends, there are glimmers of hope. The United States and Canada have seen a decrease in coal consumption of about 40 percent since 2005, Jackson said. And despite the vocally pro-coal administration of president Donald Trump, some 15 gigawatts of coal plants are slated to close this year in the U.S., a potential record, Jackson added.

"The pricing for wind and solar is now competitive with [that of] fossil fuels in many cases," Jackson added.

The transportation sector is a bigger challenge, Jackson said, as low oil prices lead consumers to drive more frequently and buy larger vehicles. Incentivizing electric vehicles — which can be charged with power generated by clean energy — would make a big impact in emissions, Jackson said.

Globally, the picture is complex. India, for example, is striving to bring any electric power at all to millions of people who have none.

"They need financial incentives to reduce reliance on new coal plants" and to build renewable-energy infrastructure instead, Jackson said.

Though it's discouraging to see emissions rising so quickly, Jackson said, he's an optimist at heart. "I believe green energy will eventually win," he said. The only question is how much warming will have to occur first and how hard it will be to rein in today's excesses.

"The higher we go in emission today," Jackson said, "the faster or the deeper the cuts need to be in a decade or two decades or beyond."

Jackson and his colleagues on the Global Carbon Project published their estimates on Dec. 5 in the journals Environmental Research Letters and Earth System Science Data.

Originally published on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Space.com sister site Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.