1 Week Until Cassini's Fatal Saturn Dive: Here's How the Probe Will Spend Its Final Days

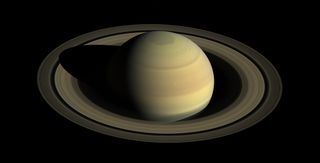

The one-week countdown has begun for the Cassini spacecraft's fatal dive into Saturn's atmosphere.

On Sept. 15, Cassini will dive straight into Saturn, collecting in-situ data from the planet's atmosphere and firing it back to Earth in the 1 to 2 minutes before breaking apart. The dive will bring a dramatic end to the probe's 13-year tenure in the Saturnian system, where it has unearthed many incredible and unexpected science discoveries.

This coming week is filled with activity for Cassini. Check out our complete coverage page for a full schedule of events and how to watch them. [Cassini's "Grand Finale" at Saturn in Pictures]

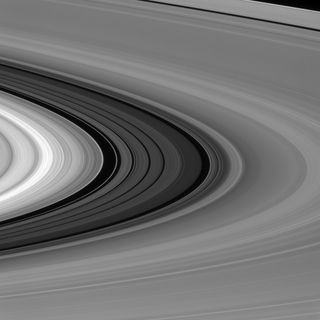

On Saturday (Sept. 9), the probe will make the last of its 22 dives through Saturn's rings — a flight path that has produced some incredible views.

On Sept. 11, Cassini will make its last distant flyby of Saturn's largest moon, Titan. From a distance of 73,974 miles (119,049 kilometers), Titan's gravity will slow down Cassini. This will prove fatal for Cassini. On Sept. 15, instead of skimming the top of Saturn's atmosphere as it has done during its last few loops around the planet, the slower-moving Cassini will dip much deeper into the atmosphere. The probe may reach depths of up to 9,300 miles (15,000 kilometers) before breaking apart, according to mission scientists.

On Sept. 13 and 14, Cassini's cameras will take the probe's last images of the system.

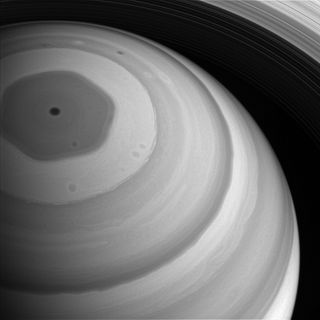

On Sept. 15, starting at 4:37 a.m. EDT (0837 GMT), the "final plunge" will begin as the spacecraft gets into position to sample the atmosphere. Normally, there is at least an hours-long delay between when the probe collects data and transmits it back to Earth, but because Cassini will only be able to transmit for 1 to 2 minutes during the final plunge, the probe will send data within 2 to 3 seconds of collecting it, Cassini scientists have said. The spacecraft will transmit data back to Earth from eight of its 11 instruments, but it will not have enough bandwidth to send images (which require larger data files), which is why the probe will take its final snapshots of the system on Sept. 14.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Cassini will enter Saturn's atmosphere at 7:53 a.m. EDT (1153 GMT), and will initially fire its thrusters at 10 percent capacity "to maintain directional stability, enabling the spacecraft's high-gain antenna to remain pointed at Earth and allowing continued transmission of data," NASA officials said in a statement. During the next 60 seconds, the probe will then ramp up its thrusters to 100 percent capacity in an attempt to keep the spacecraft's antennas pointed at Earth.

When Cassini reaches an altitude of about 940 miles (1,510 kilometers) above Saturn's cloud tops, "communication from the spacecraft will cease, and Cassini's mission of exploration will have concluded," the statement said. "The spacecraft will break up like a meteor moments later."

The probe's demise was planned by the Cassini team in anticipation of the spacecraft running out of fuel to steer itself around Saturn; because the mission will have to end anyway, the researchers decided to take the opportunity to get unique data from Saturn's atmosphere.

Cassini's destruction will serve another important purpose: protecting some of the planet's moons from Earth invaders. Saturn's moons Enceladus and Titan may possess environments that are fit to support life, and if Cassini is carrying bacteria or other miniature life-forms from Earth, planetary-protection scientists don't want those life-forms taking up residence on one of the moons. Just as invasive species on Earth can devastate native populations, an Earth-based life-form could overwhelm native life-forms on one of Saturn's moons. However unlikely such a scenario may be, its effects would be devastating. The proliferation of an Earth-based life-form on an alien moon could also make it harder for humans to identify alien life-forms in that location.

"The Cassini mission has been packed full of scientific firsts, and our unique planetary revelations will continue to the very end of the mission," said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said in a statement from the agency. "We'll be sending data in near real time as we rush headlong into the atmosphere — it's truly a first-of-its-kind event at Saturn."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter