Tales from the Exoplanet Archive: How NASA Keeps Track of Alien Worlds

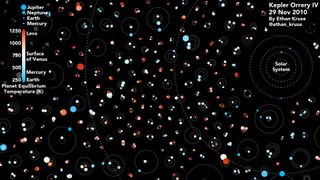

The Milky Way is littered with a vast diversity of planets: giants that blur the line between planet and failed-star brown dwarf; tiny worlds similar in size to Earth's moon; planets that take 100,000 years to orbit their suns or whip around in hours; lava worlds; ice worlds; and planets that circle multiple suns or whirling pulsars.

Scientists find them by watching stars that wobble, change gravity, vary in color or dip slightly in brightness. (This last strategy is employed by the most prolific planet hunter of all time, NASA's Kepler space telescope.) And someone needs to keep track of them all.

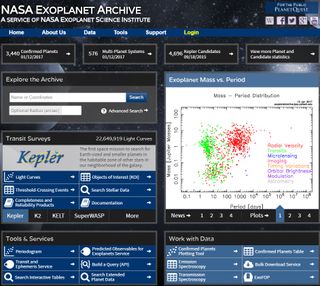

Rachel Akeson, deputy director at the NASA Exoplanet Science Institute, leads the space agency's Exoplanet Archive, which is tasked with cataloging the ever-growing horde of planets known to exist outside the solar system. [Wildest Alien Planet Discoveries of 2016]

"In 2011, there were about 700 [confirmed exoplanets]; now we're over 3,400," Akeson told Space.com. "In the next five years, there's going to be tens of thousands."

Those newly discovered exoplanets will come courtesy of various space observatories that are operating now or will come online soon. For example, the European Space Agency's Gaia mission is precisely measuring the positions of 1 billion Milky Way stars, and the work should allow astronomers to notice movements caused by the pull of many orbiting planets.

And NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is scheduled to launch to 2018 to search for planets all over the sky circling stars relatively close to the sun, using the same method as Kepler.

NASA's Exoplanet Archive will house them all; the database, which was made publicly accessible in 2011, lets researchers and enthusiasts understand the distribution and properties of planets found thus far as they come in, as well as data about the stars they orbit and planet "candidates" that have yet to be confirmed. The archive also generates graphs from the latest information to show exoplanet trends.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Right now, a big part of the Exoplanet Archive takes the shape of a large interactive table of confirmed planets, which have been checked and double-checked by the authors to make sure they're not flukes in the data. Most of the planets aren't directly imaged but rather detected via their effects on their parent stars, and confirmations can come from observation by various methods or by a strong pattern of "transits" across their stars.

The archive also hosts data about the stars' light curves when they're available, showing their brightening and dimming, as well as Kepler data that has not been confirmed as a planet's signature. It keeps a list of false positives, too, and the list is always in flux; additions and changes in status are implemented continuously.

"Things can go in and then come back out," Akeson said. "And I think in one case, something went in, came out and has gone back in. There's this series of papers in the literature — basically two groups arguing with each other via the papers — whether or not this is the planet signature versus another kind of signature."

An exoplanet's data is officially added only once it appears in a peer-reviewed publication.

As more and more planets come in, researchers can use the archive to begin to understand the galaxy's overall distribution of planets. Different methods of detection find different kinds of planets. For instance, transit measurements from Kepler or TESS are more likely to find planets that orbit close to their stars, and Gaia should generally find planets that orbit farther away, Akeson said. With current technology, systems like Earth's would still be hard to find, and so researchers don't know how common they are.

"We have no system that looks like the solar system yet, where you have these small, rocky planets on the inside and then several gas giants on the outside," Akeson said. "We're now getting to the point where we're starting to see things that are true Jupiter analogues, but the Earth analogues are very hard to find still."

Going forward, a thorough survey could help researchers understand how planetary systems evolve and why our solar system is the way it is, instead of featuring mini-Neptune and super-Earth planets like researchers have found in other star systems.

As scientists continue to discover exoplanets, the catalogue will keep growing. The archive's researchers are talking to groups of users to determine the most helpful way to display the information, and planning the best ways to wrangle and verify the new waves of planets, Akeson said.

"We are going to have to keep up," she said.

Editor's Note: The archive was launched and publicly accessible in late 2011, not 2013. Kepler data is (and TESS data will be) primarily archived at the Space Telescope Science Institute's Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.