Comet outbursts are likely caused by landslides rather than pressure-based eruptions from the icy bodies' interiors, a new study suggests.

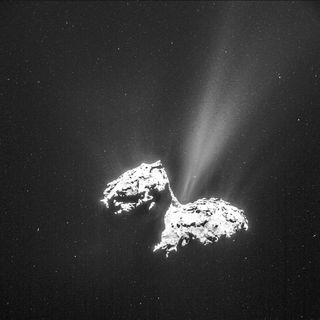

Outbursts of cometary dust — such as those observed at Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko by Europe's Rosetta spacecraft — produce plumes that look like those generated by geyser eruptions on Earth. But this resemblance is misleading, according to the authors of the new study.

"There is no internal heat source on comets to power geyser-like eruptions," study lead author Jordan Steckloff, an associate research scientist at the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona, said in a statement. "Instead, these outburst plumes are the natural result of avalanches."

Steckloff and co-author Jay Melosh, an astronomer at Purdue University in Indiana, performed computer simulations of dusty material avalanching into an active outburst area on a comet. Their results suggest a mechanism for the transient dust outbursts: a light breeze produced by the sublimation of water ice to vapor at the base of steep slopes on comets. Dusty material sliding over these cliffs is likely carried away by these breezes, forming a plume, they found.

Their results match up very well with the data Rosetta gathered during its time orbiting Comet 67P, the researchers said. For example, the spacecraft's observations indicate that outburst regions on 67P have steep slopes, and that outbursts are not associated with an increase in gas production (as would be expected if interior geysers were driving them).

"Ultimately, understanding this novel mechanism of outbursting may allow the surface processes of distant comets to be studied from Earth through ground-based observations of their outbursts," said Steckloff, who presented the results Monday (Oct. 17) at the joint 48th annual meeting of the American Astronomical Society's (AAS) Division for Planetary Sciences and the 11th annual European Planetary Science Congress in Pasadena, California.

The Rosetta spacecraft arrived at Comet 67P in August 2014 after more than 10 years of spaceflight. In November of that year, the Rosetta mother ship dropped a lander called Philae onto 67P's surface.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Rosetta mission is therefore the first ever to orbit a comet, and the first to land softly on the surface of one of these icy bodies (though Philae unexpectedly bounced twice before eventually settling down for good).

The Rosetta mother ship continued orbiting 67P until Sept. 30 of this year, when it followed Philae onto the surface in an intentional death dive that brought the historic mission to a close.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.