For thousands of years, people have craned their necks skyward, seeking meaning or a sense of perspective in the vast panoply of stars above us.

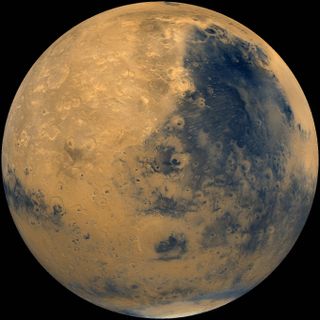

Tracy K. Smith's 2011 poetry collection, "Life on Mars" (Graywolf Press), follows in this grand tradition. The book won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry last month, with the award committee praising it as "a collection of bold, skillful poems, taking readers into the universe and moving them to an authentic mix of joy and pain."

SPACE.com recently caught up with Smith, who teaches creative writing at Princeton University. In an email interview, Smith discussed "Life on Mars," how the book honors her late father and how the Pulitzer will change her life.

SPACE.com: Your father was an engineer who worked on the Hubble Space Telescope. Is this book a tribute to him?

Smith: It is. The second section of the book is an elegy sequence for him, and there is a poem in section one, "My God, It's Full of Stars," where he makes appearances as a young man. But the book wasn't conceived that way; at first, I was simply interested in thinking about space as a kind of metaphor through which to consider some of the facts and problems of life here on Earth. [Spectacular Hubble Photos]

When my father died, those years when he was working on the Hubble came back to me, and it seemed fitting to imagine him as having somehow merged with the large mystery that the universe represents.

SPACE.com: Do you derive a sense of pride, or solace, from the fact that Hubble's still going strong after 22 years in space? And what goes through your mind when you see one of its beautiful pictures?

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

I love thinking that my father has touched some part of that machine. Since publishing this book, I've heard from other children of Hubble engineers, and they express a similar kind of pride in knowing that a parent played a role in bringing these truly astounding images to the world.

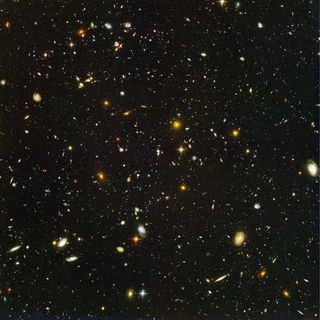

When I see those images, though, my mind zooms past my own private investment in them. First of all, they're so beautiful. They look like paintings. And yet they confirm that we are a part of something vast and eternal and unknowable. That kind of view of the literal "big picture" is both humbling and deeply affirming.

SPACE.com: In some of these poems, the narrator seems to seek perspective, or relief, by gazing at the heavens. Can space — its vastness and mysteries — help ground us here on Earth?

I think humans have always felt watched back by whatever is out there flickering in the distance. What excites me is what the imagination creates not simply in explanation of what is there, but also to explain or justify the feeling of awe and attachment that the heavens inspire.

Sometimes those answers set beautiful things into motion: compassion, hope, a desire to create something that will last. Of course, the book is also concerned with the dark aspects of being human, the inverse of that large wonder.

SPACE.com: The book also seems to suggest that accepting the mysteries that surround us can sometimes be a better course of action than always striving for answers. Did you intend to make that point?

Well, I don't think I'm prescribing any course of action for others, but I personally believe that sometimes the questions can be more productve than the answers they might lead to. A question is a pursuit, an invitation to envision and explore a series of possibilities, to struggle and empathize and doubt and believe. The question moves, whereas our sense of what an answer is can often be static, a stopping point.

SPACE.com: What do you hope readers of the book take away from it?

I hope it triggers questions. And I hope that the poems give readers the opportunity to think about private and public events in different ways, even just briefly.

SPACE.com: Do you think there is life on Mars, or anywhere else beyond Earth?

For reasons that have little concern with the plausibility of it, and with no real need to have my suspicions confirmed, I do. I don't know how anyone can see the Hubble "Deep Field" image and not feel like something else is going about its business out there.

SPACE.com: Finally, congratulations on the Pulitzer. How does it feel, and how do you think it will change your life?

Thank you. I'm deeply grateful for the recognition, and for the affirmation that the poems have resonated with some readers. I'm sure it will change my life, but I haven't really speculated about how. I'm happy just to take it in slowly.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.