Japan's asteroid sample-return spacecraft Hayabusa2 gets extended mission

The Japanese spacecraft will arrive at a new asteroid in the year 2031.

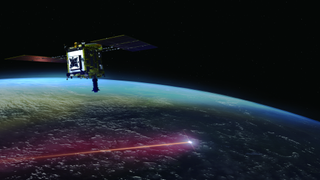

The Japanese spacecraft Hayabusa2 is currently making its round-trip return from an asteroid, bringing pieces of the space rock back to Earth. But instead of ending its run with that cosmic delivery, after dropping off its precious parcel, the spacecraft will swing back out into space to visit another rocky destination.

After Hayabusa2 delivers its samples of asteroid Ryugu to Earth in December, the craft will head off toward a new asteroid target: 1998 KY26, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) said in a statement. The spacecraft should reach the new asteroid in 2031.

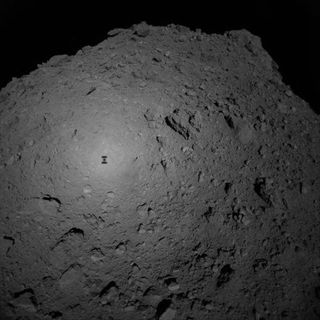

Hayabusa2 reached asteroid Ryugu in June 2018 and spent over a year studying the space rock. The spacecraft left Ryugu in November 2019 and its sample-return capsule will return pieces of the asteroid to Earth with a Dec. 6 landing in the Australian Outback.

Hayabusa2's first mission aimed to help scientists learn about the composition of the asteroid Ryugu's minerals, and thereby learn more about the origin and evolution of Earth and the solar system. This new extended mission will send Hayabusa2 on a decades-long cruise through space to focus on planetary defense, interplanetary dust and exoplanet detection.

Related: Japan may extend Hayabusa2 asteroid mission to visit 2nd space rock

Asteroid 1998 KY26 is a fast-spinning rock that circles the sun between the orbits of the Earth and Mars, occasionally clipping our planet's path on its 1.37-year trip. The round, puckered asteroid is about 98 feet (30 meters) in diameter and takes only 10.7 minutes to rotate once around its axis, according to JAXA.

The space agency stated in its Sept. 15 description of the extended mission that getting up-close to near-Earth objects this size may help scientists to adequately prepare for potential collisions to Earth by similarly-sized objects. In their outline, JAXA officials referenced the Chelyabinsk meteorite, which was roughly half the size of 1998 KY26 and caused a massive fireball explosion over Russia in 2013.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The mission will also look at the distribution of dust within the solar system by studying how zodiacal light appears at multiple points away from Earth. Zodiacal light is a celestial glow that appears to travel through the zodiac signs (which sit on the imaginary line in the night sky called the ecliptic). This glow is caused by light bouncing off pieces of interplanetary dust that wafts through the solar system.

One of Hayabusa2's instruments has an aperture that might also be able to observe bright stars. JAXA aims to watch these stars for drops in their brightness levels, which could point to the existence of an exoplanet traveling across the star's face. If Hayabusa2 detects an exoplanet, it would be the first Japanese spacecraft to do so.

The extended mission will also include a high-speed flyby of another object, asteroid 2001 CC21, JAXA officials said.

Follow Doris Elin Urrutia on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.

Most Popular