Just how many threatening asteroids are there? It's complicated.

You don't have anything to worry about right now, scientists emphasize.

So you've heard that an asteroid could slam into Earth wreaking all sorts of havoc, but just how many space rocks out there actually threaten our planet?

It's complicated, because the answer depends on what you mean by threaten.

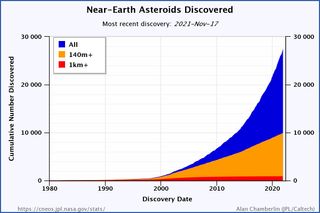

Let's start with the most important takeaway: NASA knows of zero asteroids large enough to do meaningful damage on Earth and currently on track to collide with our planet in the foreseeable future. But large asteroids hanging around Earth? We've spotted plenty of those, and scientists are discovering new near-Earth asteroids practically daily, with more than 27,000 identified to date.

"We're racking up the numbers for these populations, but at the same time, there is no known threat right now to Earth," Kelly Fast, who is a near-Earth object observations program manager at NASA's Planetary Defense Coordination Office, told Space.com. "There's nothing, there's no asteroid that we know of that poses a significant threat to Earth."

And while it may seem paradoxical, the constant rise in near-Earth asteroid tallies turns out to be the best news possible if you're worried about a potential asteroid impact.

Related: The greatest asteroid encounters of all time

The two parts of planetary defense

The art of protecting Earth from an asteroid impact is called planetary defense, and there are two key stages to the process. NASA's Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), launching later this month, is a mission designed to test the second stage of planetary defense, diverting a threatening asteroid from crossing paths with Earth.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But before anyone can even try to divert an asteroid, scientists have to find the space rock and map out its orbit many years into the future to realize that it will or may hit Earth.

"People might think planetary defense is all about deflecting asteroids but it's not," Nancy Chabot, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland and the coordination lead for DART, told Space.com. "Keeping track of the actual asteroids, identifying them and finding them is really crucial toward being able to do anything about them in the future."

Scientists have identified some 750,000 asteroids to date, but suspect there are millions of space rocks ricocheting through the full solar system. Fortunately, plenty of those stay far, far from Earth — consider, for example, residents of the main asteroid belt or the Trojan asteroids that flank Jupiter in its orbit.

In Earth's neck of the woods, that number comes down somewhat: Scientists have identified more than 27,000 near-Earth asteroids, with new ones spotted daily.

Related: If an asteroid really threatened the Earth, what would a planetary defense mission look like?

A bonanza of discoveries

Those discoveries are thanks to a team of instruments on Earth and in space that dedicate some or all of their time to spotting and cataloging asteroids. The vast majority of these discoveries have come since the late 1990s, although experts were warning of the threat posed by asteroids before then without much success.

"If you talk to the scientists who were studying this in the '80s, there's a phrase they often refer to called the giggle factor," Carrie Nugent, a planetary scientist at Olin College in Massachusetts, told Space.com. "They're basically saying that they couldn't talk about this scientific topic without people kind of laughing at them."

The work was quite difficult then, as well, with surveys relying on photographic film developed in a darkroom then used with a device that helped a human brain recognize asteroids moving against background stars. Now, modern cameras and computer programs can bear much of the brunt of identification work.

So the rise of asteroid detections has been in part a matter of technology. But increasing funding was also key, which made reducing the giggle factor vital.

One milestone was Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9's impact of Jupiter in 1994, which unexpectedly left a mark in Jupiter's clouds the size of Earth that lingered for months. "People started to think, 'Whoa, if that happened to Jupiter, what would happen if that hit Earth?'" Nugent said.

Congress got on board with prioritizing asteroid hunting, calling on NASA to identify at least 90% of first the largest asteroids, then medium ones. Today, there's a whole host of projects that detect near-Earth asteroids, whether it's their top priority or an opportunity they can make use of.

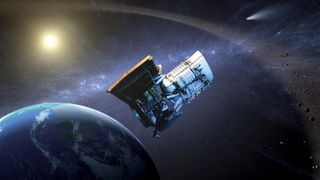

Leading the charge today are programs like the Catalina Sky Survey based in Arizona that specializes in catching smaller asteroids, the Pan-STARRS observatory in Hawaii that excels at spotting faint objects, the NEOWISE space telescope that can see the whole sky and the ATLAS telescopes in Hawaii that are tuned to the fastest-moving objects.

"It's kind of like the ecosystem, everyone has their role," Nugent said. "Everyone kind of works together with their own strengths to really cover the sky."

Others chip in when luck permits. "Wide-field survey telescopes are set up for other purposes like for astrophysics investigations for instance, and then they end up getting the asteroids that photobomb them," Fast said.

And asteroid hunters are looking forward to a few new instruments joining the team soon. Planetary defenders are particularly excited to see the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile begin observing in 2023; a space-based mission called NEO Surveyor is also in development and scheduled to launch later this decade.

"There's been a lot of work done to predict how many objects both [missions] will find, and those numbers are incredibly large," Nugent said. "It should be a huge increase in the number of asteroids and comets found, and that's always really exciting."

But surveys on their own aren't enough for planetary defense experts — follow-up observations are crucial to give scientists the data they need to accurately calculate an object's orbit. "That's the key part there," Fast said. "You want to know the asteroid's there, but you really want to know where it's going to be in the future and whether Earth is going to be in the same place at the same time."

Recipe for a "potentially hazardous asteroid"

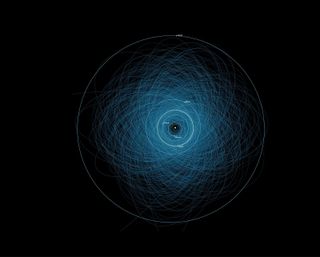

If all those observations find that an asteroid is over a certain brightness (which suggests a certain size, although the two factors don't correlate precisely) and will come within 4.65 million miles (7.48 million kilometers) of Earth, the object is automatically dubbed a "potentially hazardous asteroid." (The distance works out to one-twentieth of the average distance between Earth and the sun.)

But in most cases, despite the ominous terminology, "potentially hazardous asteroids" may as well be called "not currently hazardous asteroids." After all, these are the objects that scientists have already found, and followed, and mapped, and forecast into the future.

"It's not like I look at a potentially hazardous object and, like, break out into a cold sweat," Nugent said. "It just means that it's something we want to keep an eye on."

To those who dedicate their careers to watching the skies for an apocalypse, the asteroids not yet identified are far more terrifying; these asteroids are the ones that can pop up, suddenly uncomfortably close to Earth, too late for anyone to even try to change a rock's course.

Scientists believe they've found nearly all the largest asteroids — those larger than 3,300 feet (1 km) across — and know that these are the easiest to find anyway. And while tiny near-Earth asteroids are plentiful and difficult to find, they are also the most likely to fall apart harmlessly in Earth's atmosphere.

So it's the middle size category of asteroids — those more than 460 feet (140 meters) but less than 3,300 feet wide — that most worries planetary defense experts. "That's where it's more likely that an impact could happen," Fast said. "Even with those, we're talking maybe timescales of centuries or millennia."

As of the end of 2020, estimates suggested scientists have found just 40% of near-Earth objects of this size; this year has added 500 to the tally. While that number is impressive, NASA's planetary defense office estimates that at the current pace, it will take scientists 30 more years to have identified 90% of objects this size, a goal that Congress asked NASA to reach by 2020.

"There's more of them as you go down in size and we're still racking up the numbers every year," Fast said. "That's why the surveys are doing their job every night, so we aren't caught unaware."

The quest to map as many nearby asteroids as possible is why the tally of "potentially hazardous asteroids" and near-Earth objects in general is rising so dramatically. "It's so satisfying to see that number of asteroid discoveries creep up," Nugent said. "That feels good, it feels like you've accomplished something."

It's not just satisfying, she added — it's even comforting.

"I think it's a really nice example of science working," Nugent said. "You have a problem that seems scary, you work to understand it, it seems less scary because you know what you need to do. I think that's a really nice, calming thing about studying near-Earth asteroids."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.