U.S. 'Decades Behind' on Space Debris Threat, Official Says

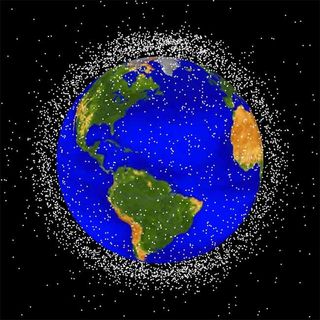

The amount of junk floating in space is getting out of handand the United States must step up its effort to control orbital trash, expertsare saying.

The chief of U.S. StrategicCommand said Wednesday that America needs better tools to monitor the orbitaldebris that's up there and plan to avoid collisions with valuablesatellites.

"We are decades behind wherewe should be, in my view," said Air Force Gen. Kevin P. Chilton in aspeech at Offutt Air Force Base, Neb. Chilton called for more personneland more sensors and equipment to study and combat the threat.

There are about 800 satellites inorbit now, and more than 20,000 piecesof debris in total, including bits of dead satellites and spent rockets, aswell as more eccentric items like loose gloves and tools that slipped away fromastronauts on spacewalks. And it's only likely to get worse as more satellitesare launched into the increasingly crowded orbital corridors of space.

"Space situational awarenessis no different than the situational awareness that we demand in any otherdomain," Chilton said. "And we do not provide that in an adequatefashion to my component commander in charge of space operations for the UnitedStates of America."

Just today NASA announced that astronauts onboard thestation may have to board their Russian Soyuz spacecraft lifeboats Fridayevening as a safety precaution in case they must evacuate because of a spacejunk impact. A small piece of debris appears poised to fly within 1,640 feet(500 meters) of the orbiting laboratory Friday night at 10:48 EST (0348Saturday GMT).

Though an actual impact is unlikely, the agency says,astronauts must be prepared when any debris comes too close for comfort.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Crowded skies

Scientists agree. A recent study calculated that "closeencounters" between satellites and debris in orbit will rise by 50 percentin the next 10 years, and by 250 percent by 2059, to more than 50,000 a week,according to Reuters.

"The time to act is now, before the situation gets toodifficult to control," study leader Hugh Lewis of the University ofSouthampton told Reuters. "The number of objects in orbit is going to goup, and there will be impacts from that."

The seriousness of the situation was made apparent earlierthis year when two communications satellites accidentally slammed into eachother, creating two huge new clouds of shrapnel floating in orbit. China alsocreated a good chunk of debris in 2007 when it purposefully destroyed one ofits orbiting satellites in an anti-satellite test.

Rising costs

Indeed, many satellite operators are noticing the problem. Thecommercial imaging satellite company GeoEye has had to maneuver some of itsspacecraft several times to avoid colliding with space junk, according toSPACE.com partner Space News. The company was forced to move its 10-year-oldIkonos satellite seventimes to evade debris.

These maneuvers are time-consuming and costly, requiringextra fuel and expert personnel to plot a safe course through space. And usingup a satellite's precious fuel resources to avoid collisions shortens its usefullifespan.

Space junk is also a critical concern for human spaceexploration, where not just money but lives are on the line. NASA scrupulouslymonitors the field for any objects that might pose a risk to the InternationalSpace Station and shuttle crews.

- Orbital Debris Cleanup Takes Center Stage

- SPACE.com Video Show - Inside the International Space Station

- Video - The Expanding Danger of Space Junk

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.