Mercury's Mysterious Bright Spot Photographed Up Close

During its most recent flyby of Mercury, NASA?s MESSENGERspacecraft caught another glimpse of the innermost planet?s mysterious brightspot.

The MESSENGERprobe skimmed just 142 miles (228 km) above Mercury at its closest approachas it whipped around the planet during the flyby, the last of three designed toguide the spacecraft into orbit around the planet in 2011.

The $446 million probe snapped several new images of Mercuryduring the flyby, despite a minordata hiccup that delayed the downlink of some of the images.

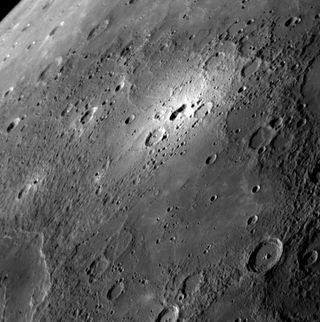

One of the new images shows a bright spot on the planet'ssurface, a feature that scientists cannotyet explain.

The new view was the third of the spot, which was first seenin telescopic images of Mercury obtained from Earth by astronomer RonaldDantowitz. The second view was obtained by the MESSENGER Narrow Angle Cameraduring the spacecraft's second Mercury flyby Oct. 6, 2008. At that time, thebright feature was just on the planet's limb (edge) as seen from MESSENGER.

Surprisingly, at the center of the bright halo is anirregular depression, which may have formed through volcanic processes. Theobject will be further investigated when MESSENGER arrives at its final orbitaround Mercury.

In the new images were also pictures of impact basins,including a double-ring impact basin, with another large impact crater on itssouth-southwestern side. Double-ring basins are formed when a large meteoroidstrikes the surface of a rocky planet.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The floor within the inner or peak ring appears to besmoother than the floor between the peak ring and the outer rim, possibly theresult of lava flows that partially flooded the basin some time after impact.

Some of these craters are relatively fresh, formed by morerecent impacts. On Mercury, like the Earth's moon, even ancient impact craterscan be preserved on the surface because there is no atmosphere to cause erosionand no plate tectonics to recycle the rock, as there are on Earth.

One set of impact craters even coincidentally resemble a pawprint.

MESSENGER was also able to image some of the same terrain asit did in its second flyby, but this time with slightly different lightningconditions. Different angles of sunlight can better show the topography of theplanet's surface.

MESSENGER made its closest approach to Mercury at about 5:55p.m. EDT (2155 GMT) when it sped by at about 12,000 mph (19,312 kph). The probethen flew behind Mercury, passing out of communications with Earth for about anhour before restoring contact.

The spacecraft is the first probe to visit Mercury sinceNASA's Mariner 10 mission in the mid-1970s.

NASA launched MESSENGER - short for MErcury Surface, SpaceENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging - in 2004. The probe swung past Earthonce and Venus twice before beginning its three Mercury flybys.

- Video - Mercury: Messenger of the Gods

- Video - MESSENGER at Mercury

- Top 10 New Mysteries of Mercury

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.