60 years of human spaceflight brings in tech changes and emphasis on diversity

Sending humans to space doesn't look the way it did in 1961.

If spaceflight used to be viewed as a race between the Soviet Union and the United States, the language today tilts toward imperfect diversity.

Yuri Gagarin's Vostok-1 mission roared into space from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in what's now Kazakhstan 60 years ago today (April 12) in 1961, ushering in a brief-yet-intense competition between the Soviets and the Americans for space supremacy that today we call the "space race." Simply put, during an incredible decade of innovation, government-funded well-chiseled astronauts rode early rockets to Earth orbit and — for a select few — to the moon's surface.

But framing the "space race" in those terms ignores a more nuanced reality. For example, U.S. President John F. Kennedy did call for Soviet collaboration on lunar missions before his assassination in 1963. An independent group of female test pilots who came to be known as the Mercury 13 unsuccessfully attempted to infiltrate NASA's astronaut corps in the same decade, while female cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova made it to space in 1963.

Related: Yuri Gagarin, first man in space (photo gallery)

Nevertheless, today's spaceflight shows wider options. There are private interests; NASA's commercial crew vehicles especially show more contractor control of design to the agency's strict safety requirements, while other companies send cargo supplies to the International Space Station.

And diversity? It appears to be everywhere. A senior, John Glenn, flew into space in 1998 at age 77. Women can celebrate recent accomplishments such as the first all-woman spacewalk and Christina Koch's nearly year-long mission in 2018-19, while recognizing they remain underrepresented even in NASA astronaut achievements, and still more among international astronaut cadres.

The International Space Station includes collaboration by nearly 20 countries; in 2019, it welcomed the first Emirati astronaut; meanwhile, the Chinese (excluded from NASA spaceflight programs) have a taikonaut program of their own and are planning to launch a new orbiting outpost this year.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

At least two LGBTQ+ astronauts have flown in space, Sally Ride and Anne McClain, although their orientations were revealed publicly only after Ride's death and a legal dispute concerning McClain. Meanwhile, astronauts of Native American, African American, Asian American and Hispanic heritage have flown in space, although their representation in the astronaut corps still lags. NASA astronaut Victor Glover is currently completing what is only the first long-duration flight by a Black astronaut.

To mark the 60th anniversary of Gagarin's flight, Space.com invited experts to reflect on how human spaceflight has evolved over the decades — and to imagine where it will go next.

Technology

The great shift of this spaceflight generation is moving spacecraft more firmly into the commercial sector. To be sure, big companies led the construction of Mercury, Gemini, Apollo, Skylab and space shuttle hardware, to name the U.S. examples, but NASA retained ownership of the technology. That's no longer the case for the current commercial crew vehicles NASA has hired SpaceX and Boeing to build.

These commercial vehicles will also build on NASA's previous space shuttle, which attempted a reusable experience to mixed success. The shuttle required longer to fix up between flights than anticipated; also, time pressure was a contributing factor to the two fatal space shuttle accidents of 1986 and 2003 that ultimately helped doom the program.

That said, the shuttle was an adaptable symbol of a generation of spaceflight that played a key role in constructing ISS. Roger Launius, NASA's former chief historian and a former curator at the Smithsonian Institution National Air and Space Museum, reminded readers in a Space.com interview that the space shuttle — despite flying from 1981 to 2011 — is really 1960s technology with some upgrades put into place over its flight years, such as glass cockpits. But these upgrades had to work with older systems, and NASA astronauts had to use late 1980s-era Compaq 286 laptops until the shuttle's retirement, Launius said.

Commercial crew — the latest generation at NASA — is very much in its infancy and its value will come only with time and experience, although Launius said we are at a great point for the moment. SpaceX has flown two successful missions with astronauts to date, while Boeing is still trying to complete a successful uncrewed test flight before boarding astronauts, a process that may wrap up this year.

But at the beginning of the pivot to industry 10 years ago, NASA's ability to reliably back up Soyuz with a commercial-led spacecraft didn't seem like such a safe bet.

Moonwalkers Eugene Cernan and Neil Armstrong were among the most vocal critics of the program; Launius recalled a conversation he had with Armstrong a few months before the latter's death in 2012 where the famed moonwalker joked about overturning the old oversight procedures with a wry, "What could go wrong?" Reflecting back on that conversation, Launius said 10 years ago "all bets were off" regarding NASA's new approach — but today, "they are looking like geniuses."

Numerous "lessons learned" from crewed and uncrewed spacecraft alike are built into the new generation of commercial crew vehicles for low Earth orbit and NASA's Orion crewed vehicles bound for the moon, he said. The electronics tend to be fly-by-wire rather than mechanical and much smaller than the less-reliable big switches of the Apollo era, for example. (Famously, the Apollo 11 astronauts had to use a ballpoint pen on the moon to fire a broken switch to get their ascent engine armed for launch.)

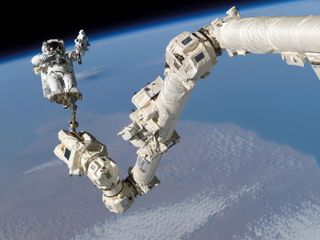

Spacesuits are also improving, with reduced bulkiness in the newer generations, Launius said — with sleek examples already available from SpaceX, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Dava Newman, and (for activities on the lunar surface) a more agile NASA spacesuit. "They allow much more manual dexterity and movement than anything in the past, and they don't blow up like the Michelin Man," he said.

NASA's success in returning to the moon will likely depend on how well commercial crew does in reducing NASA's burden of providing infrastructure in low Earth orbit, Launius added. Other outstanding questions include when the ISS will retire (2024, 2028 or later), how commercial space stations would replace it, and when the new lunar Gateway space station will be built and crewed.

While NASA moves in new directions, the Russians depend on the long-standing Soyuz spacecraft line, which first flew in 1967, to bring astronauts into space. There have been some concerns about Soyuz reliability in recent years, although the Russian space agency upgrades the capsules every few years.

In 2018, the Soyuz's rocket (also, confusingly, called Soyuz) had a sensor problem that forced a mission launching to the ISS to abort, but the Russians identified the problem swiftly and got another crew en route within weeks. That same year, a different Soyuz spacecraft developed an air leak while docked to the International Space Station; Russia identified the cause but reportedly chose not to disclose it publicly. That said, Launius lauded the Soyuz program for launching so many crews with a high success rate.

International relations

Spaceflight is far more international than it used to be, with 19 countries having visited the ISS alone; the station accepted its first long-duration crew in 2000. The international partnership of the space station has defined a generation of international relations, leading NASA to accept foreign astronauts for mission specialist roles on the space shuttle and now, anchoring collaborations for the burgeoning Artemis program.

Space law is complex, but generally operates through treaties such as the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 and intergovernmental agreements for various programs like ISS. The major ISS partners are the United States and Russia — who have not always had a smooth relationship, but have maintained the partnership nevertheless. Smaller principal partners include the European Space Agency (ESA), the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), who have contributed among them modules and robotics in exchange for astronaut and science experiment time on the station.

The CSA is an interesting case study because relative to the other partners, its robotic contributions (Canadarm, Dextre and the like) are quite small at just 2.3% of the ISS agreement; that said, Canada has a much smaller population than the other partners. Canada thus relies on collaboration for participation, and has deep relationships in particular with NASA — which flies its astronauts and allows Canadian controllers to operate robotics from Montreal — and ESA, with which Canada has a cooperation agreement that allows Canadians to access certain ESA member opportunities in science.

CSA, much like NASA, tries to emphasize Earthly benefits of its participation in space. Since Canada has a fairly sizeable population scattered in its remote north and in rural areas, ISS research on telemedicine has special importance to the CSA. The Canadians' next move will be deep-space health care, particularly on the Gateway lunar space station, to which Canada is contributing a new robotic arm, Canadarm3. NASA and CSA have already announced that a Canadian astronaut will join the Artemis 2 mission around the moon.

"We can use Gateway to further our understanding of the effects of the space environment on astronaut health and human health," Isabelle Tremblay, CSA's director of astronauts, life sciences and space medicine, told Space.com. "Especially because of the radiation that is more severe around the moon — we are outside the [protective] magnetic field of Earth — radiation study will be more important there."

Gateway will be challenging for space research, however, as it will have cramped quarters and smaller crews compared to the relatively expansive ISS that comfortably hosts six astronauts at a time. Gateway is also further from Earth and more expensive to visit, so the international partners will only put people there part-time. CSA thus foresees the need for medical devices that are smaller, more autonomous and that can potentially meet multiple purposes, Tremblay said.

Gender

According to NASA, 65 women have flown into space (out of fewer than 600 individuals overall) as of March 2021; as far as we know, astronauts of no other genders besides male and female have reached orbit. That said, we can celebrate many record-breaking women in areas such as commanding the ISS, commanding a space shuttle mission or spending nearly a year in space.

Also, the disparity in gender numbers reflects a skew to flying men in the space program during its first 30 years of operations, Margaret Weitekamp, chair of the space history department at the Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum, told Space.com; Weitekamp has a background in women's studies and lectures frequently on gender. NASA accepted its first female astronaut candidates in 1978.

One of the main channels for astronaut recruitment always has been the military academies, Weitekamp said, but it wasn't until 1976 that women could enroll, leading to graduation in 1980, just when the space shuttle program was about to begin flights. "If you look at how many people in the astronaut corps have come out of the military academies, this is significant," she said.

Now given the opportunity, modern women astronauts from the military have impressive resumes; one example Weitekamp pointed to was McClain, a West Point graduate with two master's degrees who played professional rugby. McClain flew combat sorties in helicopters and graduated from the prestigious U.S. Naval Test Pilot School before joining the astronaut corps. "You look at that resume and you think, 'That will stand up against anyone,'" Weitekamp said.

Even today, women still face challenges in spaceflight participation. NASA's mandated radiation exposure limits in 2013 were lower for women than for men, excluding several people from long-duration spaceflight, NASA astronauts said at the time. In 2014, Russian cosmonaut Elena Serova also reportedly faced down Russian media comments about her hairstyle and leaving her daughter behind for six months.

More recently, reflecting on the first all-woman spacewalk of 2019 — which happened 50 years after the first all-man spacewalk — NASA astronauts Christina Koch and Jessica Meir said the 1980s spacesuit tech they used was a barrier, although one they were able to overcome. "As the sentiment and demographics of the astronaut corps moved toward gender equality, the range of suit sizes remained an anachronism tethered to the era of its birth by technical constraints and long redevelopment timelines," the astronauts wrote in the Washington Post.

Weitekamp said we must remember, however, that reduced gender inequity is developing in large part behind the scenes of human spaceflight. NASA's Kathy Lueders, following great success helming the commercial crew program, is the first woman in charge of human spaceflight — which is based on her impressive accomplishments rather than her gender, Weitekamp said. Mission Control and planetary science are also full of women leaders notching accomplishments throughout the solar system.

Race, ethnicity and diversity

In 2020, NASA added "inclusion" as a fifth guiding value of the agency, but academics such as Lake Erie College professor Kim McQuaid have pointed out that historically, the agency has struggled with political realities in opposition to a diverse workforce, such as most NASA centers being located in the segregated American South.

Happily, spaceflight has expanded to astronauts of multiple backgrounds — although milestones are sometimes slow in coming. For example, the first long-duration mission by a Black astronaut (Victor Glover) is happening right now on the ISS, more than 20 years after continuous occupation of the orbiting laboratory began.

In an exclusive interview with Space.com in 2020, Charles "Charlie" Bolden — a former astronaut who served as NASA administrator from 2009 to 2017 — reflected on his experiences as a Black man and leader of space exploration, along with his feelings about racism and violence against people of color today, which he said are ubiquitous in American society because "this is what our nation was founded on."

The Apollo program did not include Black astronauts, nor did it ease the struggle of marginalized communities of the 1960s, Bolden added in the interview. "We don't have enough representation in the astronaut office, by women and minorities," Bolden said. "We have to have more representation."

This exclusion was recently considered in fiction. The Apple TV+ series "For All Mankind," now finishing up its second season, is an alternative history of the space program that considers what would have happened — for example — if NASA had accepted Black astronauts earlier into the program.

The forthcoming privately funded Inspiration4 mission aboard SpaceX Crew Dragon later this year will offer a new axis of diversity in human spaceflight, disability, as well as widening the income required to become a private spaceflyer. Funded and commanded by billionaire Jared Isaacman, Inspiration4 and includes a three-person crew: Chris Sembroski and Sian Proctor won their seats via contests while the third crew-member, Hayley Arceneaux, is a cancer survivor who is expected to become the first person to fly in space with a prosthetic.

CSA's Tremblay — who pointed to a non-government Canadian astronaut flying on the private Axiom Space mission set to launch in 2022 — added that the ISS and Artemis partners will keep their eyes on a very dynamic spaceflight environment for the next 10 to 15 years. "Those [private missions] are just beginning and just starting and have an impact and transform human spaceflight, making it more accessible," she said. "Hopefully it will encourage and stimulate more investment in [Earth-orbit] space exploration, and to the moon as well."

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace