Martian Soil Sample Clogs Phoenix Probe's Oven

Scientistsran into a snag when trying to deliver a sample of Martian arctic soil to oneof the instruments on NASA?s Phoenix Mars Lander, mission controllers said onSaturday.

Thelander?s robotic arm released a handfulof clumpy Martian soil onto a screened opening of the Thermal andEvolved-Gas Analyzer (TEGA) on Friday, but the instrument did not confirm thatany of the sample passed through the screen.

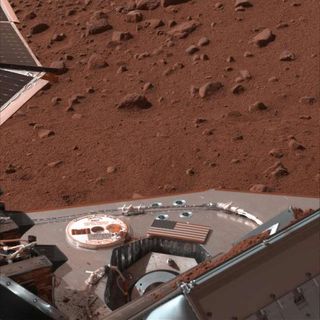

Imagestaken on Friday show soil resting on the screen over an open sample-deliverydoor of TEGA, which is designed to heat up soil samples and analyze the vaporsthey give off to determine the soil?s composition.

Theresearchers have not yet determined why none of the sample appears to havegotten past the screen, but they have begun proposing possibilities.

"Ithink it's the cloddiness of the soil and not having enough fine granularmaterial," said Ray Arvidson of Washington University in St. Louis, thedigging czar for the $420 million Phoenix mission.

The Phoenixlander touched down on the red planet on May 25 to begin a plannedthree-month mission to hunt for buried water ice in the northern polar regionof Mars. It is equipped with a scoop-tipped robotic arm, weather station, wetchemistry lab and eight ovens to study samples of Martian terrain and determineif the region could have once supported primitive life.

TEGA?sscreen is designed to let through particles up to 0.04 inch (1 millimeter)across while keeping out larger particles, in order to prevent clogging afunnel pathway to a tiny oven inside.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Mission scientists said they planned tosend new commands to Phoenix to try to shake the sample into the oven as earlyas Monday. They'll spend Sunday developing the plan for the following Martianday.

The smallvibration tool can shake the oven screen across a variety of frequencies,ranging from a light tapping to moderate shake, mission managers said.

?The soilthat we're looking at is probably sandy and it has a lot of fine grains anddust, but it is also a little bit cohesive,? Arvidson said. ?I'm prettyconfident that if we shake this stuff, we'll get some in.?

For futuresamples, they may use the robotic arm to prepare a site by poking and proddingthe Martian surface to break up clumps and clods. They may also collect smallerscoops of material to pour directly into the oven.

While thisis the first oven they've tried to pour samples into, it is designated Oven 4of eight. Despite the overflow of soil across the other oven doors, missionmanagers are confident the extra stuff won't hinder the opening of otherinstruments.

The TEGAovens have an opening just 2 mm wide and are designed to collect about 30milligrams of material for baking.

Phoenix'splanned activities for Saturday include horizontally extending a trench, dubbed?Dodo,? where the lander dug twopractice scoops earlier this week, and taking additional images of a smallpile of soil that was scooped up and dropped onto the surface during the secondof those practice digs.

"Weare hoping to learn more about the soil's physical properties at thissite," Arvidson said. "It may be more cohesive than what we have seenat earlier Mars landing sites."

- Video: Sounds From Phoenix Mars Lander's Descent

- Video: NASA's Phoenix: Rising to the Red Planet

- New Images: Phoenix on Mars!

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.