Inauguration Day for Alien Signal-Hunting Telescope

Today, inthe remote northeast corner of California,technology innovator and Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen will hit the big redbutton.

No, he won'tbe throwing heavy-duty machinery into an emergency shutdown, nor will he besending ICBMs screaming from their silos (traditional functions for ruddybuttons). Instead, he'll be christening a new telescope that, in itssignificance, could eventually outpace the Nina, Pinta,and Santa Maria.

The famoustechnologist will be inaugurating the initial 42 antennas of his namesake, the AllenTelescope Array (ATA) – the first major radio telescope designed from thepedestal up to efficiently (which is to say, rapidly) chew its waythrough long lists of stars in a search for alien signals. Within two decades,it will increase the number of stellar systems examined for artificialemissions by a thousand-fold. The ATA will shift SETI into third gear.

Thistelescope is truly a geek's barn-burner. In the last two decades, high-performanceradio amplifiers have gotten smaller and, more importantly, much cheaper. Thishas changed the recipe for building radio telescopes, and the ATA is takingadvantage of the new formula.

Consider:the single most consequential characteristic of a radio telescope (at least,for SETI) is its collecting area: the number of square meters boasted by its "mirror."There are two ways to increase this area: either build a bigger antenna, orbuild lots of smaller ones and hook them together. As an example of the formerstrategy, imagine doubling the diameter of the antenna's "dish",thereby increasing the collecting area by a factor of four. Agood thing, surely. But since an antenna is a three-dimensional device,the amount of aluminum and steel necessary for the larger antenna has gone upby a factor of eight. Expensive. It's cheaper by halfto build four of the original-size antennas.

This is asimple scaling argument, but it boils down to this: it's always more economicalto assemble a large collecting area by constructing small antennas, rather thanlarge ones.

In pastpractice, this elementary fact of antenna life was routinely diluted by thehigh cost of the receiver equipment. Check out the cryo-cooled,quiet-as-death receivers at the focus of any other radio telescope, and you'relooking at a million dollars' worth of electronics. That's why the VeryLarge Array – the iconic radio telescope in New Mexico that you've seen in a raft ofsci-fi films – has only 27 antennas. That number was a compromise betweenstructural and electronic costs.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Today, youcan festoon the focus of your antenna with high-grade receivers for about onepercent of the old price. So the paradigm has changed, and today it's better tobuild a large number of small antennas, rather than a small number of largeantennas.

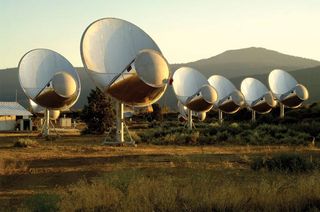

Theindividual dishes of the ATA are 6 m in diameter, small enough that you can'tsee them from Californiastate route 89, even though they're barely a milebeyond its eastern berm. Like slow-growing lotusblossoms, these antennas have methodically erupted on a lava-littered heath 300miles northeast of San Franciscoduring the last four years. Eventually, 350 dishes will grace the Hat CreekObservatory site. But the 42 now up and running are equivalent in collectingarea to a 40 m single-dish antenna – and that's large enough to start doingsome serious science.

What it can do

A lot ofthat science will be vanguardradio astronomy. Thanks to the ATA's smallindividual antennas, the instrument has a wide field of view. That is to say,like wide-angle sports binoculars, it sees a big chunk of sky all at once. (Incontrast, most radio telescopes look at the heavens with a field of viewcomparable to what you'd see through the tiniest of soda straws.) The University of California radio astronomers, who – together with the SETI Institute – are building the ATA, will fill that largefield of view with pixels to produce high-resolution radio photos of largetracts of cosmic real estate.

The combinationof wide-angle view and high resolution allows rapid surveys of our local chunkof the cosmos. And it's a hallowed axiom of astronomy that surveys nearlyalways pay off with unexpected, major discoveries.

Inaddition, by looking at lots of the sky, and looking at it often, radioastronomers can find transient phenomena: things that go burp in the night, and that otherwise would never be seen.

The newpossibilities might best be understood by analogy. Consider making a timeexposure photo of Manhattan from the Empire State Building. That'scomparable to what astronomers do now – collecting data with their radiotelescopes for hours, while staring at one patch of space. A time exposurereveals lots of subtle detail – cars parked on the streets, the filigreedfacades of the skyscrapers, and so forth. But anything that changes – thetaxis, the pedestrians, or even the stoplights – gets blurred or lost by thelong exposure. Well, with the ATA's snappy radiopicture mode, things in the universe that change will finally be seen. Prepareto be surprised.

For SETI,the ATA will be as revolutionary as a Parisian mob. Most folks, indoctrinatedby Hollywood'ssleek, blue-lit view of science – with its immaculate laboratories andaimlessly wandering engineers – imagine that SETI researchers spend their dayswith earphones on their heads, straining to pick out ET's transmissions fromthe fuzzy din of cosmic static. It isn't that way, and if it were, SETIscientists would have long ago checked into the funny farm.

The realityis more complex. Even the ATA-42, the first incarnation of this new instrument,will be able to simultaneously observe several star systems at once, whilemonitoring at least 40 million radio channels. You can't analyze all that datawith earphones, and so a sophisticated, custom software system carefullyscreens all incoming static for the tell-tale whistle of an extraterrestrialtransmitter.

For itsfirst foray into SETI, the ATA-42 will be used to scan 20 square degrees of skyin the direction of the center of our Galaxy. It will spend several monthslooking for signals coming from the direction of the Milky Way's star-clotted,inner realms. Eventually, the ATA will start a massive campaign to examineapproximately a million nearby star systems. That's a thousand times more thanall those carefully scrutinized in the past.

Today, whenPaul Allen hits the big button, 42 radio ears will pivot toward the sky likesynchronized swimmers, and the first official observations with the ATA willbegin. There'll be applause and smiles all around.

But thetrue excitement is yet to come. It's hard to imagine that such a modestcollection of small metal contrivances, pinned to the earth, and each no biggerthan a delivery truck, could somehow reveal the activities of unknown, unseenbeings on a planet a thousand trillion miles away. But a simple calculation ona small sheet of paper shows this to be true. And perhaps someday soon, thatdiscovery will be made.

- Image Gallery: Great Observatories

- Scenes from SETI@Arecibo

- All About Astronomy

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Seth Shostak is an astronomer at the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute in Mountain View, California, who places a high priority on communicating science to the public. In addition to his many academic papers, Seth has published hundreds of popular science articles, and not just for Space.com; he makes regular contributions to NBC News MACH, for example. Seth has also co-authored a college textbook on astrobiology and written three popular science books on SETI, including "Confessions of an Alien Hunter" (National Geographic, 2009). In addition, Seth ahosts the SETI Institute's weekly radio show, "Big Picture Science."