JunoCam Images Are Where Science Meets Art and NASA Meets the Public

Science and art each teach us to see the world in a different way — and Candice Hansen is living in both those worlds simultaneously, thanks to her role leading JunoCam, the crowdsourced public outreach camera aboard the Juno mission as it orbits Jupiter.

"I can tell you as a scientist that people do things with our data that I would never do, but they have given me a whole new picture of what Jupiter looks like," Hansen said during a news conference at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union held in Washington earlier this month. "[Artists] have really stretched my own perception of what Jupiter looks like."

Hansen sat down with Space.com after her presentation to talk more about her work with JunoCam and how art and science inform each other. This interview has been edited for length and clarity. [In Photos: Juno's Amazing Views of Jupiter]

Space.com: How has this program's success been received in the NASA community, and what would you tell people thinking about trying to recreate its success?

Candice Hansen: It's been quite well received. There's kind of a pro and a con that I want to illuminate. It's been a great way to get the public involved and I think that people feel real ownership in that sense and we've gotten amazing contributions from the amateur community. The con is that we are getting great science data from our outreach camera, and we don't actually have a science team to analyze it.…

The data has so much in it that could be used to understand what's going on at Jupiter. Just cataloging where the pop-up storms are and the pressure ridges that I think they form along, looking at the structure. We do have a paper out on the structure of the Great Red Spot, but now I'm looking at these brown barges and thinking, you know, they could really use some similar treatment. … We have enough images to do these time-lapse sequences where you can plot out these little white clouds, incredibly helpful as little markers for the atmospheric circulation. … The great thing is, I think the public loves us; the downside is, without a team of scientists to analyze the data, the data is getting analyzed but pretty slowly.

So if I was advising NASA, I guess I would say, "Do this again, but include some scientists on the team, and don't just throw it all onto the public."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Space.com: Can you talk about how this project has changed your perspective on the connection between art and science?

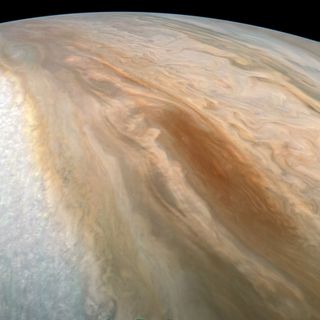

Hansen: Where do you even draw the line [between art and science]? I can't draw that line anymore. I thought I could. But I discovered within the first month of putting our data on the web that it was going to be impossible, because the kinds of things that the art community does with color brings out the structures so much more clearly than when you're looking at that subdued pastel version of the planet, which is what it really looks like.

You can put them side-by-side and you can go, "Oh, yeah, there's that feature, it's here, and there's that one, it's here," but this one pops to the eye-brain collaboration in your head, and the pastel one doesn't grab your attention in the same way. Just looking at Jupiter, I'm seeing it in a different way and it's because of all this amazing color — enhanced color, exaggerated color, artificial color in some cases — that that's happened.

And then that one image that I showed today with the North Pole and the hazes, I mean, I could see that hanging on my wall, and yet there's so much detail in it with the high hazes and why do they make those little wonderful curlicue swirls, and so there's science there to understand. But you can also just hang it on your wall and enjoy it. To me, the boundary has become very blurred from how I used to think. [Jupiter Up Close: Tour the 1st Amazing Flyby Photos by NASA's Juno Probe]

Space.com: Is there any particular structure or type of feature that you never paid much attention to before seeing them in these images?

Hansen: These pop-up storms, for example. It was perijove 6 and the lighting — the lighting changes on each pass because of the way the orbit is moving — and perijove 6 had the perfect lighting to see these pop-up storms. When we got the data for the south tropical zone and it's covered with them, I was, like, "Good lord. I don't remember ever seeing that before." So I went back, I looked at Voyager and Cassini and some of the other missions, and the clouds are there, those pop-up storms are there, but every other previous mission that has either flown by or orbited Jupiter has had a big telescope.

One of the constraints on our camera was the mass so we just have a little telescope, which means we have to be really close to Jupiter to see the same resolution that the other missions did far away. But we have a 58 degree field of view; more typically those big telescopes have very narrow fields of view, so it's like a half a degree across. So when I went back and I compared our resolution at the same resolution as the other missions, sure enough, there's little white clouds in there, little bright clouds, but when you only see this [tiny piece] of Jupiter, you don't realize that the whole south tropical zone is covered with them.

That was the eye-opener. They were there, they were in the images but because you were only seeing such a tiny little piece of Jupiter it was out of context. Even now they're not as visible as they were at perijove six because at perijove six they were all casting little shadows and so it was just punch-you-in-the-nose obvious, whereas now I'm, like, "Yeah, they're still there, there they are," but they're not as obvious.

Space.com: Is there anything that's really changed for you with Juno and JunoCam as opposed to your previous experience?

Hansen: Relying on the public was a leap of faith. Because there was no guarantee that anyone would show up. There was sort of a point in time where I was a little bit terrified that no one would come to my party. But that didn't last long.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom and Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.