Two tiny Japanese rovers began exploring the surface of the big asteroid Ryugu over the weekend — but they're not roving in the traditional sense of the term.

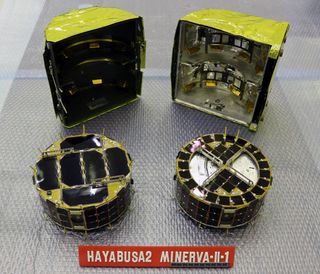

The little robots, called MINERVA-II1A and MINERVA-II1B, touched down Friday morning (Sept. 21) after separating from their Hayabusa2 mothership, which has been orbiting the 3,000-foot-wide (900 meters) Ryugu since late June.

MINERVA-II1A and MINERVA-II1B don't have wheels like NASA's Opportunity and Curiosity Mars rovers do — and there's a very good reason for that. [Japan's Hayabusa2 Asteroid Ryugu Mission in Pictures]

"Gravity on the surface of Ryugu is very weak, so a rover propelled by normal wheels or crawlers would float upwards as soon as it started to move," officials with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) wrote in a description of MINERVA-II1A and MINERVA-II1B.

So, the robots — each of which measures 7 inches wide by 2.8 inches tall (18 by 7 centimeters) and weighs 2.4 lbs. (1.1 kilograms) — hop instead. They do this by moving a "torquer" in their interior, which rests atop a disk-shaped turntable.

"By rotating the torquer, a reaction force against the asteroid surface makes the rover hop with a significant horizontal velocity," a team of researchers led by JAXA's Tetsuo Yoshimitsu wrote in a 2012 study outlining the concept. "After hopp[ing] into the free space, it moves ballistically. With this mechanism, by changing the magnitude of torque, the hopping speed can be altered, so as not to exceed … the escape velocity from the asteroid surface."

The MINERVA-II1 rovers control the direction of their hopss by manipulating the orientation of the turntable, the scientists added. These hops can last for 15 minutes and cover about 50 feet (15 m) of horizontal distance. And the rovers are designed to make their exploration decisions autonomously, without direction from Earth.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This mobility system was not invented out of whole cloth for the Hayabusa2 mission. The same basic idea was built in to the original MINERVA hopper, which flew aboard JAXA's first Hayabusa spacecraft. That mission arrived in orbit around the stony asteroid Itokawa in 2005 and managed to return small grains from the space rock's surface to Earth five years later. But MINERVA did not land successfully on Itokawa. (And, in case you're wondering, MINERVA stands for "Micro Nano Experimental Robot Vehicle for Asteroid.")

More Ryugu landings are coming soon, if all goes according to plan. Hayabusa2 totes another bantam hopper called MINERVA-II2, as well as the shoebox-size lander MASCOT ("Mobile Asteroid Surface Scout"), which was built by the German space agency, DLR, in collaboration with the French space agency, CNES. [Asteroid Basics: A Space Rock Quiz]

The 22-lb. (10 kg) MASCOT, which carries four scientific instruments, is scheduled to land on Ryugu on Oct. 3. Despite its "lander" designation, MASCOT will be mobile, and it will hop in a manner similar to that of the MINERVA-II1 duo.

MASCOT's system "encompasses a swing arm, made out of tungsten, which is accelerated and decelerated by a motor, causing the whole system to swing, so that MASCOT can move by 'jumping' and thus maneuver itself into the position required to conduct the experiments," DLR officials wrote in a MASCOT description.

This swing arm is inside MASCOT, just as the MINERVA-II1 torquers are inside those little hoppers. MASCOT's system will enable the lander to right itself as needed and hop up to 230 feet (70 m) from spot to spot, DLR officials have said.

MINERVA-II2, meanwhile, is a surprisingly complex beast. This little hopper, which was developed by a consortium of Japanese universities, packs four different mobility systems into its 2.2-lb. (1 kg) body: an "environmentally dependent buckling mechanism," a "leaf-spring buckling mechanism," an "eccentric motor-type micro-hop mechanism" and "a permanent magnet-type impact-generation mechanism," according to a Hayabusa2 fact sheet.

MINERVA-II2 is an "optional" rover, this fact sheet states. So, it's unclear at the moment if and when the rover will head down to Ryugu's surface.

The $150 million Hayabusa2 mission launched in December 2014. Its main goals involve shedding light on the solar system's early history and on the role that carbon-rich asteroids such as Ryugu may have played in helping life get going on Earth.

In addition to obtaining all the data gathered by the mothership and surface craft at the asteroid, Hayabusa2 aims to return a sample of pristine Ryugu material to Earth. If everything goes according to plan, this cosmic dirt and rock should touch down under parachute in Australia in December 2020.

NASA has its own asteroid-sampling mission underway. The U.S. space agency's OSIRIS-REx probe is scheduled to arrive in orbit around the carbon-rich asteroid Bennu on Dec. 31 and return samples from the space rock in September of 2023.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.

Most Popular