Mining Moon Ice: Prospecting Plans Starting to Take Shape

GOLDEN, Colorado — A diverse range of scientists, engineers and mining technologists have begun blueprinting what hardware and missions are required to explore and establish a prospecting campaign for water ice at the poles of Earth's moon.

Why have they warmed up to ultra-cold lunar ice? Water ice can be converted to oxygen, liquid water and rocket fuel. Exploiting the stores of this resource — which is thought to be abundant within permanently shadowed polar craters on the moon — could help pioneers survive and thrive on the moon, and help entrepreneurs turn a profit.

For example, United Launch Alliance is maintaining its $3,000-per-kilogram ($1,360 per lb.) offer, first made in 2016, for moon-derived propellant delivered to low Earth orbit. The satellite communications industry could well be the first market for space resources. [Photos: The Search for Water on the Moon]

Wanted: more data

Experts gathered last month for a Space Resources Roundtable, held here at the Colorado School of Mines. The Roundtable and the Planetary & Terrestrial Mining Sciences Symposium were staged in collaboration with the Lunar and Planetary Institute.

Scientists, engineers and exploration advocates are keen to characterize lunar ice as an economic resource. To do so, however, more data is needed about lunar ice deposits, its distribution, concentration, quantity, disposition, depth, geotechnical properties and any other characteristics necessary to design and develop extraction and processing systems.

"A highlight of this year's Space Resources Roundtable, besides the diverse and international participation of space agencies, companies, startups and academia, was the presence of the U.S. Geological Survey. They contributed many insightful and valuable discussions at the meeting," said Angel Abbud-Madrid, director of the Center for Space Resources at the Colorado School of Mines.

"Another U.S. government agency [USGS] is now getting involved in the space-resources field. They bring centuries of experience in terrestrial geology to assessing the value of resources of the moon, Mars and asteroids," Abbud-Madrid added.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Confluence of interests

"We are surprisingly close to mining on the moon," said Philip Metzger, a planetary scientist at the University of Central Florida's Florida Space Institute in Orlando. "The business analysis by the Colorado School of Mines and the United Launch Alliance looks quite good. It looks even better when we factor in geopolitical concerns, which international, cooperative lunar industry helps to address," he told Space.com.

Metzger said that many nations want to do science on the surface of the moon. "Lunar science becomes far more effective when we depend on the in-situ resources to support the science," he said. "I think this confluence of interests makes it likely we will see lunar mining in about a decade."

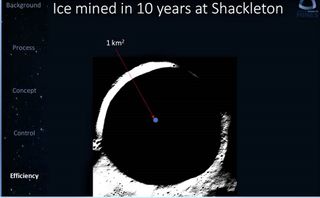

A decade is the fastest lunar mining could possibly begin, Metzger said: "When you add up the time needed to characterize and quantify the resources, followed by developing and deploying technologies to mine, it takes about 10 years."

That said, the biggest uncertainty is still the form of the lunar ice. The method used for mining this resource depends on what form it is in.

"We don't know if it is primarily 'dirty snow,' or if it is gravel-sized chunks of pure ice mixed into otherwise dry regolith, or something else," Metzger said. "We need to have rovers driving around and drilling on the moon as quickly as possible to resolve this."

Metzger said rover operations should be performed in parallel with the broader exploratory activities: trying to figure out where the ice is, in what concentrations and with what kind of variability across the lunar surface.

"Instead of starting broad with orbital missions, then later narrowing down to detailed sampling on the surface, I think we need both to begin right now," he said.

Thermal mining

"We're at the tipping point of a new era in space commerce, where private industry, NASA and international collaborators are joining together to realize the dream of launching humanity into the solar system," said Hunter Williams, a Colorado School of Mines researcher. "There has never been a more exciting time for furthering science, turning a profit or promoting international cooperation than right now."

Williams, along with Chris Dreyer and George Sowers, also of the School of Mines, detailed a low-cost mission to discover the extent of water resources on the moon, as well as a newly developed extraction technique, "thermal mining," that transforms lunar water ice into rocket fuel.

Thermal mining makes use of a high-efficiency energy source — direct sunlight. Using multiple gimbaled mirrors around permanently sunlit peaks near deep, shadowy craters, thermal mining can tap into up to 99 percent sunlight through the year, advocates say. And using direct solar energy transfer into a super-cold crater can provide variable heating, allowing managers to control the production rate.

Williams said that thermal mining is an efficient, scalable, sustainable method of ice mining at the lunar poles. Offering lower weight and fewer moving parts, the technique provides a feasible alternative to traditional excavation concepts, he said.

Mixed messages

Two big takeaways from the meeting, held from June 12 to June 15, were underscored by Gerald Sanders, lead for the In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU) System Capability Leadership Team at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston.

First, there was excitement about the possibility of government and commercial exploration of the moon from all the meeting participants. Sanders said he hadn't seen such enthusiasm since 2004, the early days of NASA's Vision for Space Exploration plan, which sought a crewed lunar mission by 2020.

"Attendees thought commercial exploration of the moon is now more likely and real due to NASA's commercial cargo and crew activities, as well as recently released requests for information and proposals," he said. [In Images: How Moon Express' Solar System Exploration Plan Works]

But there was also some confusion by the nongovernment attendees on what seemed to be mixed messages from NASA, Sanders said.

On the one hand, there's the message that lunar exploration is important, and there is a strong push for early lunar missions, especially aimed at space resources, Sanders said. "That's contrasted by NASA's decision to cancel the Resource Prospector mission, which had been advanced and advocated for over the last several years as a means of initiating characterization and development of lunar polar water."

Two communities

"Most agree that lunar exploration for science, of all types, will benefit from lunar exploration for mineral resources, and vice versa," said Leslie Gertsch, an associate professor in geological engineering at Missouri University of Science and Technology in Rolla.

The two communities — science people and resources people — continue to figure out how best to collect data for mutual benefit, Gertsch said.

Gertsch also noted that the U.S. Geological Survey showed up in force at the School of Mines gathering.

"This is very encouraging, as the USGS collects much of the basic information for Earth-based mineral production planning, though mining companies supplement it quite a bit during their own exploration," Gertsch said.

This crucial government service, she added, is based on economic geology — the study of how economically usable mineral deposits form and how they can be identified, "a science that would benefit enormously, on Earth, from study of more bodies than just Earth." [Earth Quiz: Do You Really Know Your Planet?]

Danger and opportunity

Technological and economic issues aren't the only things to be ironed out before space mining can become a reality; there are legal concerns as well.

"Who owns the resources, and how do we stop one country from using them to gain extreme military advantage in space?" Metzger said.

The best way to solve this is to form an international alliance, Metzger said. Once this alliance is formed, he said, joint mining operations could quickly become viable.

This approach benefits science, and it's also mutually beneficial for economic development and for the long-term health of Earth, Metzger said," making civilization no longer dependent on a single planet for all it needs."

"Lunar resources present us with extremes of both danger and opportunity," Metzger said. "The only safe way forward is to fill this vacuum with the good before it is filled with the bad."

Leonard David is author of "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet," published by National Geographic. The book is a companion to the National Geographic Channel series "Mars." A longtime writer for Space.com, David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. This version of the story published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He was received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.