Now You Can See Every Comet Photo (& More) from Europe's Rosetta Probe. Enjoy!

Gazing at the night sky can offer a respite from life's minutia or disarray, and any viewer wanting to be awed and inspired by the heavens will delight in the new series of images recently released by the European Space Agency (ESA).

Nearly 100,000 high-resolution images of a comet, two asteroids, Earth and Mars are now all available to the public online. Over a 12-year journey, ESA's Rosetta mission gathered a large collection of data and visuals to better understand the ancient solar system. And in May of this year, the mission's OSIRIS camera team delivered to ESA the final set of images, which cover a period from July to September 2016, according to a statement released by ESA on June 21.

"Having all the images finally archived to be shared with the world is a wonderful feeling," Holger Sierks, principal investigator of the OSIRIS camera, said in the statement. "We are also pleased to announce that all OSIRIS images are now available under a Creative Commons license." The incredible photos and corresponding data can be viewed in both ESA's Archive Image Browser and their Planetary Science Archive.

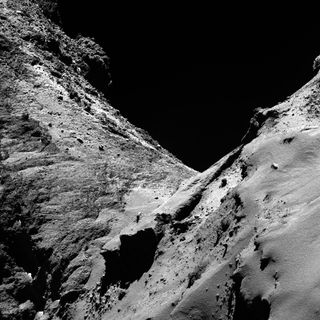

It's breathtaking to view a comet with such detail that you can imagine what the surface might feel like to the touch. The smooth features, the dusty ground and the array of background stars are impressive to behold.

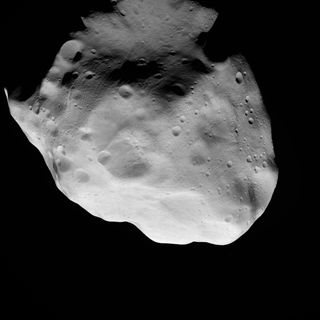

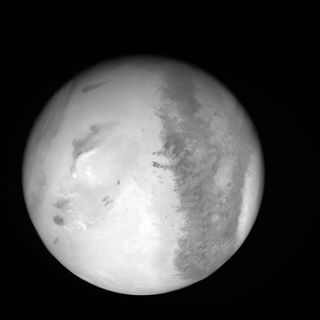

The Rosetta mission traveled through the inner solar system — and took flyby shots of Mars and Earth en route, as well as the asteroids 21 Lutetia and 2867 Steins — to study how the sun's energy warmed the icy surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. And Rosetta studied the comet's composition by getting very, very close. Rosetta took its final images as the spacecraft descended to the comet's surface following elliptical orbits during the mission's final two months, and according to ESA's statement, it took its last glance within just 20 meters (65.6 feet (20 meters) from the space rock.

"The final set of images supplements the rich treasure chest of data that the scientific community are already delving into in order to really understand this comet from all perspectives – not just from images but also from the gas, dust and plasma angle – and to explore the role of comets in general in our ideas of Solar System formation," said Matt Taylor, ESA's Rosetta project scientist, in the agency's statement. "There are certainly plenty of mysteries, and plenty still to discover."

Philae, Rosetta's lander, is visible in several photos — the end result of a long effort to determine where exactly Philae landed on the comet's surface. Dust and gas escaped the comet and caused problems in locating the lander until just recently, officials said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Now with this plethora of images, people can enjoy a quick trip through our cosmic neighborhood.

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.

Most Popular