Alien Life Hunt: Oxygen Isn't the Only Possible Sign of Life

Alien-life hunters should keep an open mind when scanning the atmospheres of exoplanets, a new study stresses.

The time-honored strategy of looking for oxygen is indeed a good one, study team members said; after all, it's tough for this gas to build up in a planet's atmosphere if life isn't there churning it out.

"But we don't want to put all our eggs in one basket," study lead author Joshua Krissansen-Totton, a doctoral student in Earth and space sciences at the University of Washington in Seattle, said in a statement. [5 Bold Claims of Alien Life]

"Even if life is common in the cosmos, we have no idea if it will be life that makes oxygen," Krissansen-Totton added. "The biochemistry of oxygen production is very complex and could be quite rare."

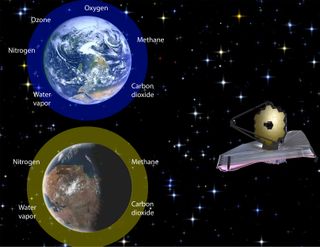

So, he and his colleagues took a broader view, studying Earth's history to identify combinations of gases that, if observed together by future instruments such as NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, would be strong evidence of life. They came up with what they think is a good candidate: Methane (CH4) and carbon dioxide (CO2), without any appreciable carbon monoxide (CO).

As their chemical formulas show, methane and carbon dioxide are very different molecules. Their co-occurrence is indicative of an "atmospheric disequilibrium" — a term that gets astrobiologists pretty excited.

"So you've got these extreme levels of oxidation. And it's hard to do that through non-biological processes without also producing carbon monoxide, which is intermediate," Krissansen-Totton said. "For example, planets with volcanoes that belch out carbon dioxide and methane will also tend to belch out carbon monoxide."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In addition, many microbes here on Earth gobble up CO greedily. So, an abundance of this stuff in a planet's air would argue against the presence of life for several different reasons, study team members said.

Proposing to look for compounds in disequilibrium isn't a novel idea. For example, other astrobiologists have suggested that the combination of methane and oxygen in an exoplanet's air would be a strong sign of life.

But the new study could help open researchers' minds to possibilities beyond oxygen, which was not detectable in Earth's atmosphere for most of life's history on this planet. (The gas didn't start building up in our air until about 2.5 billion years ago, when photosynthesis really took off. And it may not have reached reasonably high levels until 600 million years ago or so, scientists have said.)

"What's exciting is that our suggestion is doable, and may lead to the historic discovery of an extraterrestrial biosphere in the not-too-distant future," study co-author David Catling, a professor of Earth and space sciences at the University of Washington, said in the same statement.

The new study was published online today (Jan. 24) in the journal Science Advances.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.