How Did Venus Get Its Stripes? NASA Mission Could Find Out

A proposed NASA mission could solve the mystery of how Venus got its stripes.

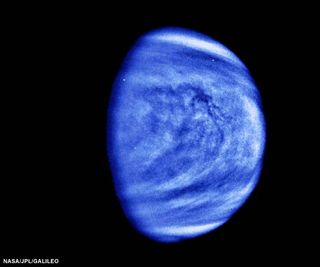

To the human eye, the cloud tops of Venus may look smooth and monochrome, but in ultraviolet light, dark and light streaks decorate Earth's sister planet. The cause of these stripes is unknown, and Venus' thick, blistering atmosphere (which is hot enough to melt lead) has made the world a difficult planet to study.

Now, NASA has invested money in a proposed mission that could help researchers figure out what causes the Venusian bands, according to a statement from the agency. The mission would use a very small space probe, equipped with cutting-edge technology, the statement said. [The 10 Weirdest Facts About Venus]

The CubeSat UV Experiment, or CUVE, would orbit Venus over the poles and study the planet's atmosphere in ultraviolet and visible wavelengths of light. Venus' cloud tops scatter visible light, which makes the planet look like a smooth, featureless globe. But some of the material in the clouds absorbs ultraviolet light, creating the dark stripes, according to the statement.

"The exact nature of the cloud-top absorber has not been established," Valeria Cottini, CUVE principal investigator and a researcher at the University of Maryland, said in the statement. "This is one of the unanswered questions, and it's an important one."

One hypothesis that could explain how Venus gets its stripes posits that material from

"deep within Venus' thick cloud cover" could rise into the cloud tops via convection (in which hot material in a fluid naturally rises above cold material). Winds would then disperse the material along breezy pathways, creating streaks.

The CUVE team has now received additional funding from NASA's Planetary Science Deep Space SmallSat Studies, or PSDS3, to further develop the mission concept.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The spacecraft would be a cubesat, or a miniature satellite that typically consists of single unites that are about 10 inches (25.4 centimeters) cubed. CUVE would include a miniaturized ultraviolet camera "to add contextual information and capture the contrast features," according to the statement, and a spectrometer to study the UV and visible light in detail.

CUVE could also carry a "lightweight telescope equipped with a mirror made of carbon nanotubes in an epoxy resin," officials said in the statement. "To date, no one has been able to make a mirror using this resin."

The nanotubes and epoxy would be poured into a mold, heated to harden the epoxy and then coated with a reflective material. This telescope would be lightweight and easy to reproduce, and would not require polishing, which is typically time-consuming and expensive, according to the statement.

"This is a highly focused mission — perfect for a cubesat application," Cottini said in the statement. She later added, "CUVE would complement past, current and future Venus missions and provide great science return at lower cost."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter