Awe, Luck & the Science of Solar Eclipses: Q&A with Astronomer-Artist Tyler Nordgren

With the 2017 total solar eclipse just three weeks away, Space.com is turning to the experts to learn about eclipse history and what to expect on the big day.

Tyler Nordgren is an astronomer by trade and a professor of physics at the University of Redlands in California whose recently published book, "Sun Moon Earth: The History of Solar Eclipses from Omens of Doom to Einstein and Exoplanets" (Basic Books, 2016), is a journey though both the human history of eclipses and Nordgren's own eclipse-chasing adventures (and misadventures).

Nordgren is about more than eclipses, though; he's worked with the National Park Service since 2007 to promote education in astronomy and protect the night skies from light pollution, preserving the views of the stars. (He wrote a book on the subject, as well: "Stars Above, Earth Below: A Guide to Astronomy in the National Parks.") He's also been an invited speaker on eclipse cruises and is something of an evangelist for eclipse watching.

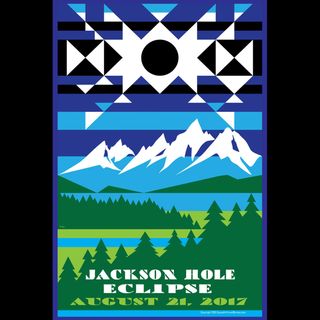

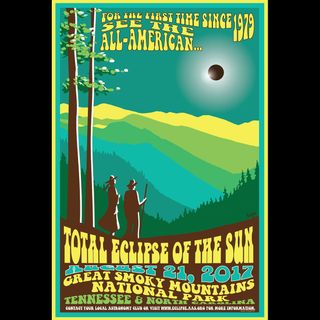

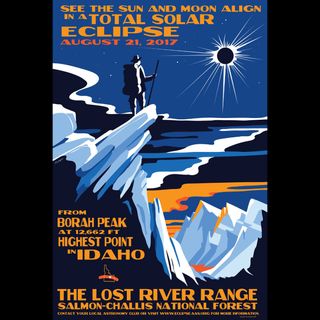

Space.com spoke to Nordgren about what drives an eclipse chaser and how, sometimes, people just get lucky. [The Amazing 2017 Solar Eclipse Posters by Astronomer-Artist Tyler Nordgren]

Space.com: What prompted the book? Was it just an appreciation of eclipses?

Tyler Nordgren: One prompt was a formative story, about the eclipse of 1979. I was 9 years old for that eclipse, and missed it. People were saying it was dangerous to look at it.

20 years later, and I was at an [International Astronomical Union] meeting in Budapest. It just so happened it was during the Aug. 11, 1999, eclipse in Europe. It blew me away.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

I'd always known I wanted to see the big 2017 eclipse. I thought that was the thing I'd be waiting my life to see — it changed my outlook on what this year was going to mean. It wasn't just a matter of me seeing for myself. I was cheated out of this when I was 9 years old, and I wanted to make sure nobody else was.

So in 2013 I was asked to be a speaker for an eclipse trip in the Atlantic. [The total eclipse was on Nov. 3]. There were 120 eclipse chasers; these were folks that had seen 17 of these things. Seeing the one in '99, getting a chance to talk with these folks, was amazing. [The book] was a chance to share the awe and the mystery.

Space.com: What do you want readers to take away from it?

Nordgren: The terrible thing is — and I shouldn't say this in front of my publisher [laughs] — eclipses are one of those things you don't need to know anything at all about them.

But if you want to know more, here's how people have been awed and amazed by this, this is what this phenomenon has done for us down through the eons. All these ways that eclipses contributed to the knowledge that we are on a planet, all these myriad ways our lives can be touched by this.

Space.com: You note in your book that eclipses have contributed a lot to science. Can you give some examples?

Nordgren: If you didn't have satellites, and didn't have eclipses, would you be able to study the corona [the sun's outer atmosphere]? I do not think so. Even with our satellites, that mask they use [called a coronagraph, which allows the satellite to block the glare of the sun so it can see the corona] blocks out the inner corona. That's what we wait for: that inner corona, which is otherwise completely invisible.

Also, eclipses were one of the big ways of getting longitude. You wait for an eclipse and compare the time it happens at two different places. That was what [scientist and explorer] John Wesley Powell tried to do. He knew there was going to be a total eclipse in the U.S. It was going to be partial where he was, and if he could at least observe the partial eclipse, he'd know his longitude. What the path was of the Colorado River at that point was a total mystery; we knew where it ended and we knew where it began, that was it. So on the day of the eclipse he climbed out of the canyon — this one-armed guy — to see it, but the weather was those summer monsoons.

Space.com: During the eclipse of 1919, Sir Arthur Eddington attempted to measure the deflection of light by gravity, to test Einstein's then-new theory of general relativity. You mention in the book some dispute over whether it really proved what Eddington thought.

Nordgren: There was some idea that it might not have been exact enough. The folks at Greenwich Observatory reran his experiment with an automated plate scanner [which measures the positions of stars on the photographic plate] and they confirmed it. At the very least, the data that was taken — the plates Eddington used that were taken had sufficient information there. Whether Eddington himself was able to extract that, I have to admit that is an open question. You're talking about measuring seconds of arc [1 second of arc is 1/3600th of a degree]. The guy was a good scientist — I'm going to have to say that he had data that was good enough.

In any case, it's been confirmed multiple times. There was another expedition in 1922, for the eclipse in Australia, so Eddington got his result. [Total Solar Eclipse 2017: When, Where and How to See It (Safely)]

Space.com: At least two groups are preparing to involve amateurs in duplicating Eddington's experiment. What do you think of duplicating that experiment now?

Nordgren: This is citizen science — you're getting citizen science involved in general relativity. We don't need to do that experiment again, but to be able to get the public involved in this groundbreaking experiment — it's a wonderful opportunity.

Space.com: You also talk in the book about luck, and its role in making astronomical observations, especially of eclipses and planetary transits across the sun, which are much rarer. You discussed one astronomer who seemed to have the worst luck: Guillaume Joseph Hyacinthe Jean-Baptiste Le Gentil, who tried to see the Venus transits of 1761 and 1769. His first attempt was thwarted by war and the second by weather. Did he get to see any eclipses?

Nordgren: There's no mention of him seeing an eclipse. He was going for that Venus transit. No problem, he thought. We'll just have to tool around the Indian Ocean for 10 years. He thought, "I've got this planned out; I'm going to do everything right."

But just at every single stage it goes wrong and none of it appears to be his fault. It's one of these humbling things — you do the best you can and sometimes you get thrown a curve ball. He eventually brought himself home, after like 11 years, but here he was hoping to have a bunch of observations that would make his career and he got nothing.

Space.com: Are there other eclipse or astronomical expeditions that went really wrong?

Nordgren: Not quite that bad. I've got to reading lots of journals. There was one about an expedition in the late 1800s, you had some American astronomer on a gunship down in South America. He climbed up into the Andes and had malaria, the altitude was making him sick, and he still made all the necessary observations. You can just tell from the official report this guy was in agony. When you read some of the old eclipse reports, it's pretty amazing.

In a way, it underscored the need for the ideal astronomer on these expeditions to not get caught up in the excitement — just make the observations necessary. It reminded me of the first astronauts training for Gemini and Mercury missions. NASA ran them through endless drills so that they accomplish the task, run through the checklist and everything goes by the book. The training was to not get caught up in the excitement.

Space.com: Have you had any particular "bad luck" eclipses?

Nordgren: I was going to one in the Faroe Islands [in 2015]. In the Faroes, the change in temperature during totality was enough to make it cloud up on me. The rain had begun to clear up and we thought the Nordic gods were looking down in favor on us. It was the most epically beautiful location, too. But we missed totality.

Space.com: Speaking of luck, in the book Columbus fools the native Caribbeans with his prediction of the eclipse, but that wouldn't have worked on the Mayans or Aztecs, would it? They could keep track as well as he could.

Nordgren: Yes. They would have known that something was coming. The fact that he was on an island worked in his favor. If he'd run across them they'd have said "tell me something I don't know."

Also, depending on exactly where he was, there would be a chance the eclipse would end by the time it rose — a nonzero chance he could miss the lunar eclipse entirely. But with Columbus essentially all of his mathematical errors canceled out.

Space.com: What was the most awe-inspiring eclipse you ever saw?

Nordgren: You always remember your first. But other than that, the 2013 [eclipse] from the deck of the sailing ship was the most dramatic. We had beautiful clear weather the morning of the eclipse when the storm came in. We had the entire ship, and the captain was determined to get us into the path of totality. I said, "Look, we just need to find one clear spot in all of this between these two latitudes." The captain got us into that spot 5 seconds before totality began. When you're griping the rigging, standing on the bowsprit, with the dramatic alignment with the worlds above, that's something. [Rare Solar Eclipse Wows Skywatchers Across Atlantic, Africa (Photos)]

Space.com: What about eclipses on other planets?

Nordgren: On Jupiter — I did the math a while ago — it worked out you could be on one moon and if the other moon is at just the right point, if the two pass, you could see a solar eclipse by one moon from the other moon. On Mars, you'd get this really strange annular eclipse, because Phobos and Deimos [the two Martian moons] are so small. I also did some math about [the recently discovered exoplanet system] Trappist-1. Trappist-1 has seven little tiny planets. If you're within the error bars for the semimajor axes and potential size, you could be on the seventh planet, Trappist-1 h, and see Trappist-1 g at just the right angular size, and get a total eclipse like here on Earth. Given the difference in orbital velocity you could get totality for something like half an hour.

Space.com: Eclipses are often hard to see for most people. Do you think that's why few appreciate them?

Nordgren: Put it this way: I'm out there in the wilds of eastern Oregon. This is one of the least visited parts of the U.S. And there will be thousands of people trying to come here, but it's not easy. But looking ahead to April 8, 2024, we have a path of totality that covers Dallas, Cleveland, Buffalo — these are major cities. So here's a chance for all the people that missed out — big cities with massive hotels.

Space.com: Any advice for people watching the eclipse?

Nordgren: Yes. First off, even polarized sunglasses really don't protect you. During totality, the corona is as bright as the full moon, and the sun is a million times brighter. Solar eclipse glasses are designed to reduce the sun's light by a factor of 1 million. That's far more than any sunglasses do. Also, sunglasses reduce light in the visible and ultraviolet, but infrared is also dangerous. Eclipse glasses reduce the IR as well.

I've seen people use all sorts of things, even brown beer bottles. Use real eclipse glasses.

Using binoculars or a telescope is dangerous — any filter has to be on the end of binoculars. Looking at the eclipse through a telescope is safe during the total phase, but you've got to make 100 percent certain the instant you see the second "diamond ring" look away! I would not do that at all. Project the image onto something else like a piece of cardboard.

I'd recommend just watching it without any equipment the first time. [Editor's Note: This would mean not looking at the sun at all until it is completely obscured by the moon.]

Space.com: Does the rest of your family share your eclipse enthusiasm?

Nordgren: I'm the only one in my family that's ever seen one. My wife is a planetary scientist, she doesn't see what the big deal is. I suspect she's kind of humoring me at this point.

You can learn more about Nordgren's work, including his amazing series of 2017 solar eclipse travel posters, at his website: http://www.tylernordgren.com/.

Editor's note: Space.com has teamed up with Simulation Curriculum to offer this awesome Eclipse Safari app to help you enjoy your eclipse experience. The free app is available for Apple and Android, and you can view it on the web. If you take an amazing photo of the Aug. 21 solar eclipse, let us know! Send photos and comments to: spacephotos@space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.