NASA's Kepler Space Telescope Finds Hundreds of New Exoplanets, Boosts Total to 4,034

This story was updated at 2:45 p.m. EDT.

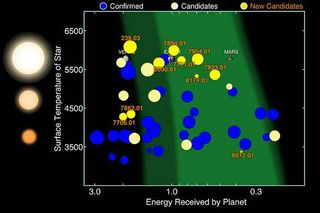

NASA has unveiled the complete set of data from the first four years of the agency's Kepler Space Telescope mission, which stared at a single patch of the sky in the search for alien planets. The result: Kepler has discovered 219 new candidates since NASA's last data unveiling, including 10 near-Earth-size planet candidates in the so-called habitable zone around their stars where the conditions are just right for liquid water to exist on a planet's surface — a key feature in the search for habitable worlds.

The new discoveries boost Kepler's total to 4,034 candidate planets during its mission, 2,335 of which were later confirmed by follow-up observations, NASA officials said in a statement. The 10 newfound potentially Earth-size worlds bring Kepler's total up to 50 of that type of exoplanet, with more than 30 of those being confirmed, NASA officials said during a briefing today (June 19).

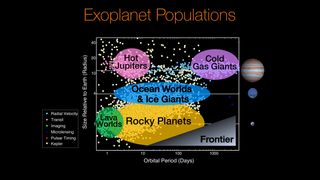

The researchers also revealed a surprising divide between small, Earth-like planets and mini-Neptunes gleaned from the data. [From the Exoplanet Archive: How NASA Keeps Track of Alien Worlds]

"With this catalog we're able to extend [our analysis of planets' demographics] out to the longest periods, those periods that are most similar to our Earth," said Susan Thompson, a Kepler research scientist for the SETI Institute in California and lead author on the new catalog study.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"As a result, this survey catalog will be the foundation for directly answering one of astronomy's most compelling questions: How many planets like our Earth are actually in the galaxy?"

According to the researchers, Kepler discovered more than 80 percent of all planet candidates and confirmed exoplanets ever found. This catalog is the final release of data from Kepler's four-year primary mission, which examined a narrow patch of sky in the Cygnus constellation. Kepler launched in 2009, and completed its primary mission in 2013. Now, it's in an extended mission known as K2.

To find planets, Kepler uses the transit method: The space telescope tracked stars over a long period of time so scientists could identify when the stars dimmed briefly, which could suggest a planet crossing between the star and Earth.

That process discovered potential planets like the newly found KOI 7711 (short for Kepler object of interest), an exoplanet that appears very much like Earth — just 1.3 times Earth's radius at an orbit that lets the planet feel about as much radiation as Earth gets from the sun. For KOI 7711 and the other planets, the percent the star dimmed let researchers determine its size, and the frequency of the dimming revealed the orbit.

To determine which dimmings of the 200,000 stars observed by Kepler were likely to be planets, the data went through an intensive vetting process. As Thompson described, about 34,000 signals were found — both transiting planets and noise that could have come from the camera or star itself. After vetting, the total came down to about 4,000 candidates, 50 of which were Earth-size and in the habitable zone.

The researchers then put simulated transits into the data and recorded how many were actually picked up by the software — determining how many transits the process might have missed. And they put noise through the process, too, checking how many were marked as transiting planets — so they knew how many planets were likely to be false alarms. [NASA's Planet-Hunting Kepler Explained (Infographic)]

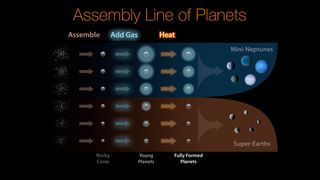

During the briefing, researchers also discussed a surprising distinction they found between super-Earths, which are rocky planets with thin atmospheres, up to about 1.75 times Earth's size, and mini-Neptunes that form dense gas balls 2 to 3.5 times the size of Earth.

A research group used the Keck Observatory in Hawaii to gauge the size of 1,300 stars measured by Kepler, which allowed them to more precisely pinpoint the stars' sizes — and therefore the size of their potential planets. They found that while researchers had thought there was a smooth population containing the whole range of sizes between 1 and 4 times that of Earth, there was a much sharper divide.

"This is a major new division in the family tree of exoplanets, somewhat analogous to the discovery that mammals and lizards are separate branches on the tree of life," said Benjamin Fulton, a researcher at the University of Hawaii in Manoa and the California Institute of Technology and lead author on the Keck study.

That sharp divide likely comes from the planet formation process, Fulton said: Planets' rocky cores form from smaller pieces, and then the protoplanet's gravity attracts hydrogen and helium gas. A little bit of gas makes the planet much bigger, putting it on the mini-Neptune side of things. Planets in the middle, Fulton said, can suffer a setback that puts them back on the rocky super-Earth side of things: The newfound atmosphere can be baked away if the star is too close by or there's not enough to start with.

While the Kepler data set provides the best-ever glimpse of exoplanet demographics for one slice of the sky, future telescopes — like NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite set to launch in 2018 — will allow researchers to follow up on these Kepler finds to characterize the planets even more. They may someday even take direct images of exoplanets with tools like Hubble Space Telescope's successor, the James Webb Space Telescope (also set to launch in 2018). Plus, additional data from Kepler's current K2 mission will give researchers a glimpse into what things look like in other parts of the sky, revealing planets around star clusters of different ages, with different iron contents, and many more low-mass stars than Kepler saw the first time around, the researchers said.

"It feels a bit like the end of an era, but actually I see it as a new beginning," Thompson said. "It's amazing the things that Kepler has found. It has shown us these terrestrial worlds, and we still have all this work to do to really understand how common Earths are in the galaxy."

"I'm really excited to see what people are going to do with this catalog, because this is the first time we have a population that is really well-characterized and we can now do these statistical studies and really start to understand the Earth analogues out there," she added.

Editor's Note: This article was updated at 2:45 p.m. EDT to include more details and background from NASA's press conference. Video produced by Space.com's Steve Spaleta.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.